In a move that may shine light on how museums and institutions could share the responsibility of preserving cultural heritage, Alabama’s Talladega College has entered into a partnership with three art institutions to share six monumental artworks.

The alliance—between the historically Black college and the Toledo Museum of Art, Art Bridges, and the Terra Foundation for American Art—ensures that six murals by artist Hale A. Woodruff will remain visible to the public while supporting the college’s long-term financial health.

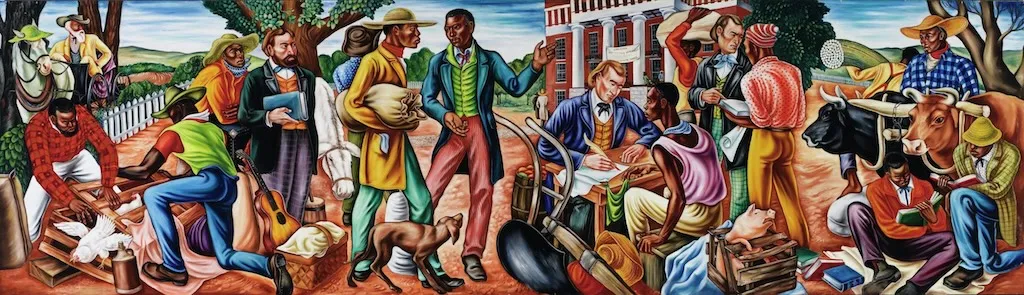

Woodruff’s murals, painted between 1939 and 1942, depict key moments in African American history: the Amistad uprising in 1839, the Underground Railroad, and the founding of Talladega itself just after the end of the Civil War. For decades the works have hung in the school’s Savery Library, where they were rarely seen outside the college community. Beginning in 2012, the works underwent conservation and toured the United States as part of a traveling exhibition organized by the High Museum of Art before returning to campus in 2020.

Now, the Toledo Museum of Art has acquired The Underground Railroad (1942), while Art Bridges and the Terra Foundation have jointly acquired the three Amistad murals. The remaining two murals—Opening Day at Talladega College and The Building of Savery Library—will remain at the school. Under the terms of the agreement, all six will be periodically reunited on campus, ensuring their continued connection to the institution that commissioned them.

For Talladega, the partnership was born of necessity. The small liberal arts college, whose endowment hovers below $5 million, faced a financial crisis in 2024 severe enough to threaten payroll. “We had to look at every asset we had,” board chair Rica Lewis-Payton told the New York Times earlier this week. Rather than simply deaccessioning its greatest treasures, the college sought a solution that could address its immediate needs without severing its ties to the murals—or to Woodruff’s legacy.

Hale A. Woodruff, The Underground Railroad, 1942.

Historical Collection of Talladega College, Talladega, Alabama. Acquired by Toledo Museum of Art.

“This was never about a transaction,” Adam M. Levine, director and CEO of the Toledo Museum of Art, told ARTnews in an interview this week. “It was about a relationship. We asked how we could be the best partner to an institution that was trying to achieve multiple objectives. Once we clarified that, the structure fell into place.”

Levine called the partnership “mutually beneficial,” not only because it provided the college with stability but because it gave the murals a broader audience. The Underground Railroad, he said, “is especially resonant for Toledo, a city that served as a final stop on the Underground Railroad for enslaved people escaping to freedom in Canada via the Great Lakes.” The painting will be on long-term display at the museum, with community programs planned in Ohio and in Talladega to deepen engagement with the work.

The partnership model that Talladega College adopted—one that divides ownership while preserving collective stewardship—is part of a growing trend in the museum field. In 2021, the Dia Art Foundation and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston jointly acquired Sam Gilliam’s Double Merge (1968), while the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Vincent Price Art Museum together own 21 photographs by late photographer Laura Aguilar. Last year, LACMA and two other LA museums—the Hammer Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art—announced that they would share more than 350 works donated by collectors Jarl and Pamela Mohn and continue to grow the collection.

But the continued involvement of Talladega, the mural’s longtime steward, is what differentiates this model from other recent ones. In a phone interview with ARTnews, adviser Nina del Rio, who helped design the Talladega ownership structure, called it a way to share “that’s realistic and sustainable. When we started, we asked what the college wanted to achieve. The answer was clear: to make the murals accessible, to raise Talladega’s profile, and to secure its future. Those objectives had to live alongside each other.”

Del Rio and her team at del Rio | Byers initially explored selling all six murals together to a single public institution, but few museums could commit to the scale—or the shared stewardship—that Talladega required. “Some partners wanted to buy outright,” she said. “But this demanded collaboration. It took a year of careful planning to find institutions that would share responsibility in perpetuity.”

For Del Rio, the result represents “an alternative solution” to the all-or-nothing logic of deaccession. “The paintings stay in the public domain, the story of Talladega is consistently told, and the college gains the means to thrive,” she said.

Woodruff’s murals, commissioned under Talladega president Buell G. Gallagher and board chair George W. Crawford, were conceived in the same spirit of interracial cooperation that founded the college in 1867. Gallagher envisioned the new Savery Library, built by both Black and white laborers, as a monument to “intellectual advancement and harmony.” Woodruff, who had recently returned from working with Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, was drawn to the project’s social idealism.

Hale A. Woodruff, The Trial of the Amistad Captives, 1939.

Historical Collection of Talladega College, Talladega, Alabama. Acquired Jointly by Art Bridges Foundation and Terra Foundation for American Art

The resulting works—rhythmic, vividly colored, and narratively rich—are among the most significant American murals of the 20th century. With its sweeping diagonals and muscular figures, The Mutiny on the Amistad, for example, stands as a monument to resistance and freedom. The Underground Railroad transforms an episode of history into an allegory of solidarity across race and geography.

In the new partnership, that ethos of cooperation lives on, with the murals’ reunion scheduled roughly every six to 12 years. “One of the reasons for reuniting the murals at Talladega every few years,” Levine said, “is not just for the students—it’s to create a moment that draws people to the campus, that gives the college visibility, and that contributes to the local economy.”

For Talladega, the agreement represents both a lifeline and a declaration of intent. “The result of more than a year of careful consideration and due diligence,” Lewis-Payton said in a statement, “benefits Talladega College in extraordinary ways and honors those who came before us, including Hale Woodruff, whose paintings will now be seen by millions across the United States and around the world.”

Levine sees in the partnership a lesson that extends well beyond this case. “We often get trapped in storytelling as if there are binaries,” he said. “But there are always hybrid solutions that lead to better outcomes. The more we tell these stories, the more we expand the sense of what’s possible.”