Symbolism perhaps suffers from middle-child syndrome. From the storied vanguardism of its older sibling, Impressionism, to the legendary antics of its younger ones, Fauvism and Cubism, it can be easy to forget the febrile movement that reared its head from the late 1880s into the early 1900s. The firstborn and the babies share a family resemblance: The eldest child—who pushed the limits of perception and paint—sees his work, a few decades later, taken to new heights in the hands of the youngest. That, at least, is the story of modernism—a tale in which Symbolism, with its embarrassing fixation on figuration, sometimes schlocky tropes, and an arsenal of abstruse references, has no place.

If Symbolism is cursed first with forgettability, it is afflicted next with ill-definition. And if the former is a quirk of art historiography, the latter can be laid squarely at the feet of its hand-waving theorists, who declaimed it with gusto if not always lucidity. Like many middle children, Symbolism was more concerned with defining itself against its predecessor than in actually defining itself. Emerging from a moment when modern life had come to feel especially incoherent, Symbolism made a credo of doubt, uncertainty, and mystery.

It was born, as the poet Jean Moréas declared in 1886, an avowed “enemy of didaction, declamation, false sensibility and objective description,” but what that meant in practice was vague. As early as 1892, the critic Max Nordau complained that the movement “assumes a special title, but in spite of all sorts of incoherent cackle and subsequent attempts at mystification it has, beyond this name, no kind of general artistic principle or clear aesthetic ideal.” Another century of spilled ink has not gotten us much closer, which is perhaps why the Art Institute of Chicago’s “Strange Realities: The Symbolist Imagination” keeps the question open, sidelining arguments about what Symbolism was to instead show off a stunning range of works, all pulled from its own collection, that could conceivably fall under the movement’s auspices. Even Moréas’s manifesto is held till the final room—an attempt, one suspects, to let the pictures have their say in a story that tends to be overdetermined by its literary side.

Vincent van Gogh: Weeping Woman, 1883.

What do the pictures say? Though Symbolism’s forefather, the poet Stéphane Mallarmé, held that a work should suggest rather than show, these paintings are not always so coy. Some, it’s true, maintain a smug silence. In Edvard Munch’s Anxiety (1896), roughly carved lines make skeletons of vacant faces. A crowd of cosmopolitan corpses look at us and say nothing. Their silence is unnerving—perhaps even more so than Munch’s more familiar The Scream (1895), which opens the show beside Van Gogh’s Weeping Woman (1883).

Yet Van Gogh’s peasant seems less a symbol than a study. Where Symbolism sought to prize from art its representational role—to shift its attention from the observable world to invisible realities—Van Gogh scrupulously renders pinned hair, heavy skirts, and clenched fists. From those details, we can begin to spin a story–about a worker fallen on hard times, or a mother pushed to desperation, the kind of prescriptive tropes that Van Gogh took from the Realists. So, what, exactly, makes this drawing Symbolist? The curators’ decision to avoid finicky (and always dubious) distinctions sometimes licenses too much.

Still, laxity has its advantages. “Strange Realities” goes beyond Symbolism’s usual suspects, reminding us that even if French journals boasted the movement’s manifestos, Paris was never its most interesting center. Alongside the requisite Odilon Redons are lesser-known artists like the Swedish painter Gustaf Fjaestad, whose Moonlight, Örebro (1897) hovers on the edge of Expressionism. A woman, silhouetted against the night, leans a bit too heavily on the chain that separates her from a lake where yellows and teals squirm like one great gelatinous amoeba—less a reflection than a projection of her own nervous state.

Gustaf Fjaestad:

Moonlight, Örebro, 1897.

Angst is ubiquitous in the Symbolist repertoire, and adherents of all nationalities perfected that peculiar blend of arrogance and doubt mythologized in the creative type. Brooding men abound, though Max Klinger’s self-portrait Night (1888–89) loses some of its melodrama next to Gustav Adolf Mossa’s Self-Portrait or Psychological Portrait of the Artist (1905). Head raised in reluctant recognition, Mossa stares beyond us as a snake coiled around his neck poises to pounce and a scorpion scurries up his chest. An erect violin knob, peeking from behind fingers that fondle a brush, suggests that the artist has read his Freud. Behind him, to prove the point, hang the artist’s lodestars—his father’s painting, among them. Below it, five bloody bursts drip burgundy on a wall stained with one unsubtle handprint. The color is gorgeous, but it is hard not to cringe at how much this painting wants your attention. Works by several self-involved Symbolists could easily pass for those of a moody teenager.

But a room of political works defends them from charges of unrepentant solipsism. František Kupka appears here before his conversion to abstraction, pitting a rowdy proletariat against timorous businessmen and vainglorious priests and dubbing the lot of them Fools (1899). The Belgian artist James Ensor’s The Entry of Christ into Brussels in 1889 (1898) offers a “Where’s Waldo”-type hunt for Jesus that takes us through a parade of socialists, anarchists, and actual clowns—dunces all, it seems to say. Agitprop this is not: Symbolism’s penchant for the cryptic cuts up against sloganeering.

Odilon Redon: The Beacon, 1883.

Yet the vagaries endemic to Symbolism could also be politically expedient, as Paul Signac’s In Times of Harmony (1895–96), originally titled In Times of Anarchy, reminds. In decades marked by a power struggle between reactionary and insurgent groups, censorship was strict, and artists—as Signac and his Neo-Impressionists knew too well—could be caught in the crossfire.

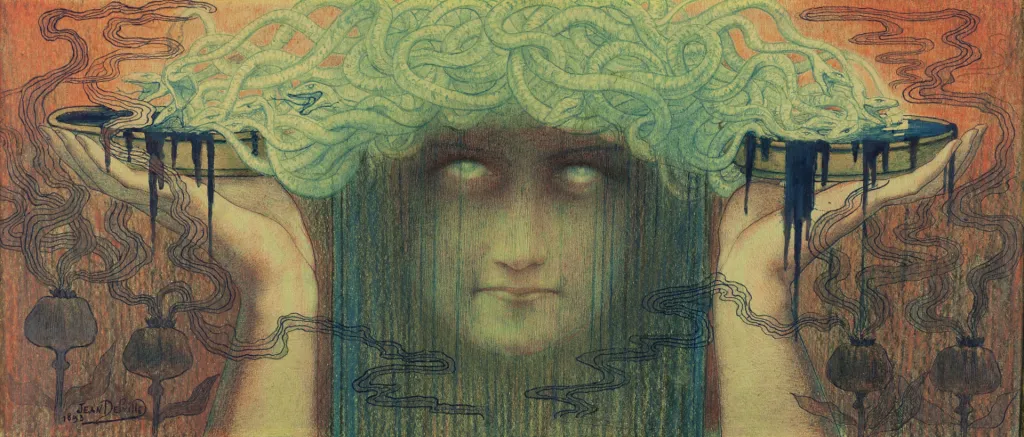

Supporting the suggestion that Symbolists were not wholly out of touch was their response to the “New Woman” movement of the 1890s—albeit with mixed results. Women demanded more, and Symbolists offered them options. A woman could now be an “addict, biblical protagonist, colonial fantasy, prostitute, violent perpetrator, [or] virgin,” as the show wryly observes. Sometimes she could have it all—the drugs, the sex, the mythic title, and the orientalist overtones, as in Jean Delville’s Medusa (1893), this show’s pastiche of a poster child. Marie Laurencin’s sapphic Song of Bilitis (1905), hung here as if in apology for the clichés of her colleagues, is a half-hearted reminder that Symbolist women could be artists, too.

Stronger is a drawing elsewhere by Käthe Kollwitz, whom we might associate more readily with her antiwar lithographs of the 1920s. Inspiration (1908) features no femme fatale, but an aging peasant, her body broken from years of submission. Attempting to shake her from that slumber is an allegorical figure who proffers what at first appears to be a maulstick, but on second glance turns out to be a scythe. It’s a symbol whose politics are clear: Inspiration is no one’s property, and art and action can go together. But the question remains: Will she take it up?