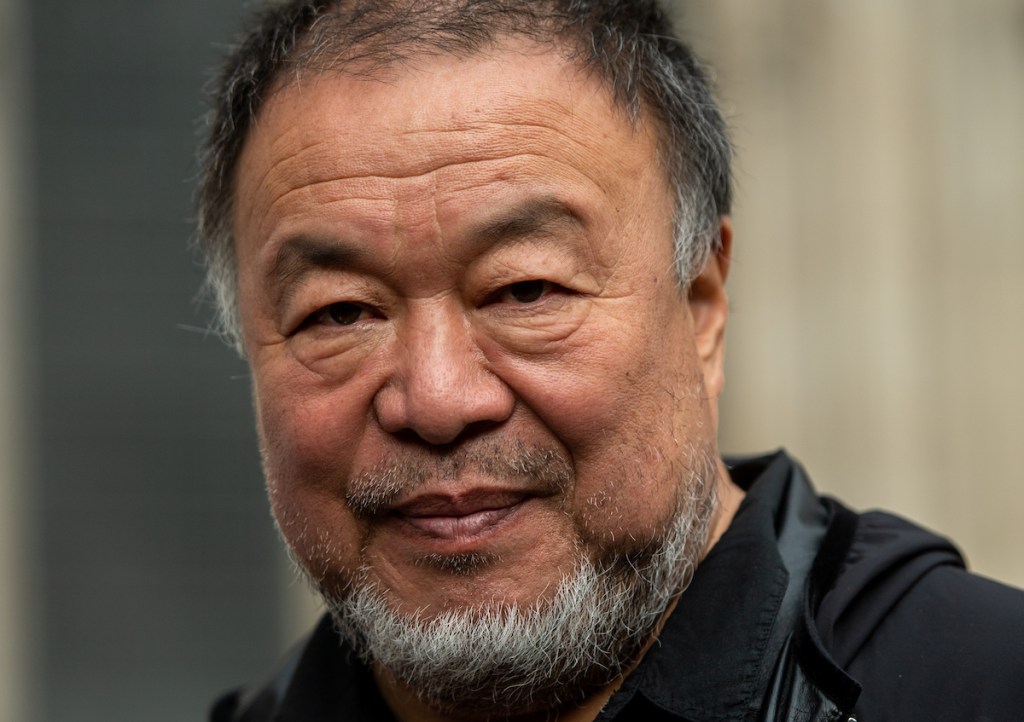

Chinese artist Ai WeiWei has claimed that German newspaper De Zeit portrayed him in “a distorted and unjust manner” in an article it published on Thursday. His claim follows another he made earlier this year, alleging that the paper censored an article he wrote for it.

On Sunday, he posted on X that he received an interview request in August from Die Zeit through the Ribbon International PR agency. “When I heard this, I told my assistant to ensure that they were aware of an unpleasant encounter we had recently experienced with Zeit Magazin,” WeiWei wrote. “In July, Zeit Magazin had invited me to write an article, asked me to revise it, then trimmed and edited the piece—only to ultimately refuse to publish it. It is evident that their refusal to publish the article was an act of censorship. In that article, I had responded truthfully to Zeit Magazin’s prompt: ‘What I wish I had known about Germany earlier.’ The content probably did not align with what they had hoped for, and so they chose not to publish it. So when Die Zeit approached me to conduct an interview on 14 September, I was genuinely surprised. I thought: really, again?”

When the artist asked Ribbon International if it was aware of the previous situation, he claimed it said it was “full informed.”

WeiWei agreed to the interview, which took place on September 14 in Kyiv, where he recently unveiled a large-scale installation at the city’s Pavillion 13 responding to armed conflict. He was willing to talk because “I try to fulfil interview requests as much as possible because I believe freedom of speech is the cornerstone of both my political and artistic life,” he wrote on X. “I believe in open expression, transparency, and the importance of speaking one’s mind. Only through such openness can a society be reasonable and empathetic.”

He met the Die Zeit journalist, Olivia Kortas, at the Bursa Hotel and said she was surprised when he placed his own recorder on the table alongside her own. “She repeatedly emphasized certain points that seemed unrelated to the exhibition,” he wrote. “When she initially requested the interview, she stated that it would be part of a report on my exhibition at Pavilion 13. Yet her questions felt disconnected. So I asked her whether she had actually seen the exhibition at Pavilion 13. Had she attended—particularly my public conversation with Maksym Butkevych, a journalist, human rights activist, and war veteran who has been detained in a Russian prison for over two years—she would have asked more substantial questions. That public conversation, for example, was deeply meaningful. She admitted honestly that she had not seen the exhibition, which was fine, and I still answered all her questions sincerely.”

When Kortas’ article was published last Thursday, it was titled “The Annoyance,” and the sub reads, “Ai Weiwei intervenes in the war in Kyiv with a work of art. And, quite defiantly, offends many.”

“Many feel offended by Ai Weiwei’s work, which not resonated with them,” the article said. “And it’s also his statements that make Ukrainian artists suspicious. A year ago, he said in an interview that Germany was adding fuel to the fire with its arms deliveries. In our conversation, he repeats the statement: ‘Any nation that doesn’t try to stop the war but instead adds offensive weapons is adding fuel to the fire.’ He also says that Russia should first end the war and then ‘the EU or NATO should not further encourage the continuation of the war.’ This almost sounds as if the EU or NATO bears some responsibility for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.”

On X, WeiWei wrote that he felt compelled to respond to the article. “Firstly, what she wrote was not an accurate reflection of reality; in fact, it included distortions and a subjective value judgement that did not reflect the exhibition’s actual impact or intentions. Their vengeful actions stem from a narrow and petty form of censorship.”

WeiWei added that he was speaking out to “highlight how a media outlet in Germany—one that is supposed to be intellectual and has a long history—can act in such a distorted and unjust manner. Ironically, this provides me with new insight into German society and its future. While this is not the image I had hoped to see, I believe that when a society loses its sense of justice and falls under the ideological control of a select few, it risks reliving the darkest chapters of its history.”

De Zeit did not reply to ARTnews’ request for comment by the time of publication.