The Azadi Hotel was built in the 1970s as the Hyatt Crown Tehran in the full flush of Iran’s oil wealth. From high ground, it towers over a city still reeling from June’s so-called Twelve Day War, when Israeli warplanes bombed residential areas and state infrastructure, triggering an exodus of millions of Tehran’s residents. In October, the Azadi Hotel played host to a glamorous, million-dollar art sale—a sign of the resilience of the elite in a country that has been almost totally isolated under the toughest sanctions in history.

For a week, the country’s premier—and only—auction house Tehran Auction displayed 120 works of art by Iran’s most prized Modern and contemporary artists in one of the hotel’s upper floors. On 4 October, they sold for 134 trillion Iranian toman, or $1.5m minus fees, a paradoxically strong showing for the art market in a country that is barred from all international banking transactions, has run out of drinking water, and cannot import enough medicine.

In central London a few weeks later, works by Iranian Modern and contemporary artists went under the hammer at Sotheby’s and Christie’s. It was their weakest showing in years, continuing a slowdown in the prices for Iranian art in the West, as diametrically-opposed markets have risen for the same commodity. Sanctions, geopolitics and cultural tastes have produced a closed, booming market in Iran and a sluggish, stagnant market in the rest of the world.

Those artists who have an international profile have gone up in value exponentially

Spending more than ever

Ali Reza Sami-Azar, Tehran Auction’s founder, tells The Art Newspaper that “the real value” of his sales increases every year, despite perpetual economic crises. This year inflation in Iran reached 45% and GDP growth stayed at 1.59%, while the currency has fallen in value so much that authorities have decided to slash four zeroes from banknotes. Tehran Auction’s most recent total, $1.5m, was less than its highest dollar-value sale, at $8m in 2019. Nevertheless, more Iranians are spending larger sums on art inside the country than ever before, despite a reduction in what Sami-Azar calls “free-market prices”.

Farmanfarmaian’s work at James Cohan’s Frieze London stand

Photo: Stephen White; courtesy Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian and James Cohan; works: © the artist

Tehran Auction does not operate in the free market: sanctions have made it extremely difficult for Iranians to take their money abroad, and most luxury goods cannot be imported to Iran. At the same time, macro-economic instability has punctured the reliability of the Iranian stock market. “Industry, agriculture, every other sector is in a terrible condition, so investment has no benefit,” says Sami-Azar, who points out that art offers a tangible repository of value: “You think about buying art in the same way as gold.”

Almost every sector of the Iranian economy has been placed under US-led multilateral sanctions. This has led to economic hardship for the country’s population, with sharp rises in the prices of essential goods, like food, which is produced domestically and priced in toman. At the same time, countries such as Russia, India and China have continued to do business with the Islamic Republic, providing certain people and organisations with valuable foreign currency.

Although the recipients of this money are unable to easily move this money out of the country due to sanctions, they enjoy outsized purchasing power at home. Consequently, consumption has been conspicuous on the streets of Tehran, with a rise in high-end housing and hospitality developments. Organisations and individuals affiliated with the regime are thought to dominate the economy, enriching a well-connected few. “There are legit buyers,” says the Iranian art consultant Dina Nasser-Khadivi, “but also an element of money laundering.”

In this context, Tehran Auction has cornered a large chunk of the demand for luxury goods, due in part to its high-profile and slick production standards. “Their catalogues are beautiful,” says the British Iranian collector Mohammed Afkhami. “The professionalism with which they do the auction is quite impressive.”

The Iranian dealer Hormoz Hematian estimates that auctions represent “about 50%” of the art business inside Iran, with the other half being transacted through a proliferation of galleries, representing both Modern masters and up-and-coming contemporary artists.

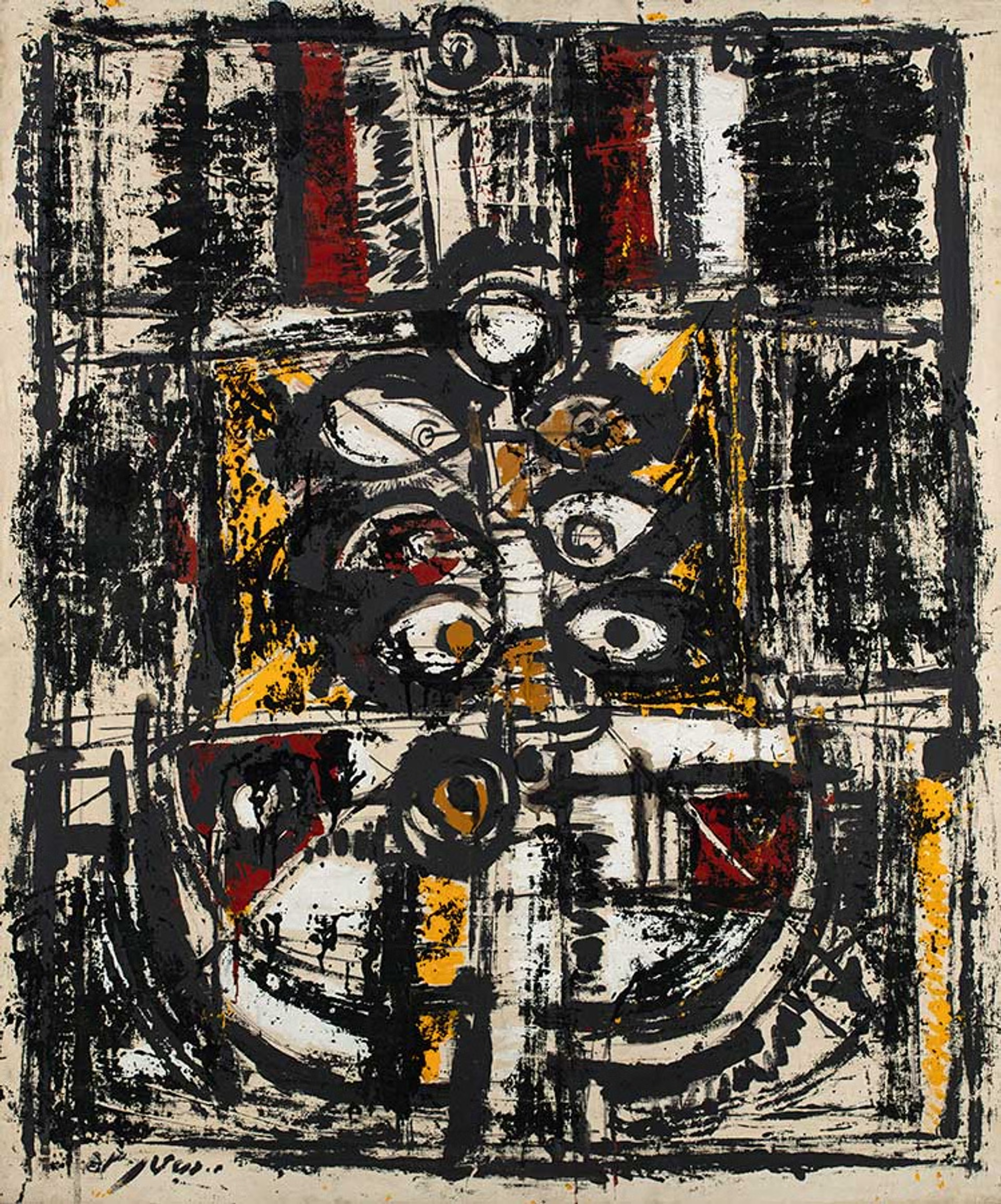

Massoud Arabshahi’s Untitled (1974), being auctioned at Christie’s this month

Courtesy Christies Images Ltd

“Generally speaking, it has been on the rise”, Hematian says, although he points out that, “with the devaluation of the [currency], those artists whose works were not pegged to the dollar have lost money”. Artists who are represented abroad set their value by their dollar price history.

For example, works by the pioneering Iranian Modernist Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian (1922-2019) were exhibited by the New York gallery James Cohan at the Frieze London this October. Consequently, those wishing to buy her works in Iran will be quoted prices in dollars. “Those artists who have an international profile—and are therefore pegged to the dollar—have gone up in value exponentially,” says Hematian, who added that mid 20th-century Modernists are most sought-after, regardless of pricing.

More interest in Iran

In Tehran Auction’s most recent sale, a painting by Reza Derakshani (born 1952), whose thick impasto paintings rework Iran’s heritage of manuscript miniatures, sold for $154,000, while a layered, abstract canvas by Massoud Arabshahi (1935-2019) fetched $138,000. Barely a month later, comparable works by both painters are being offered by Christie’s in London in their November sale of Modern and Contemporary Middle Eastern Art, with estimates starting at £20,000.

According to Sami-Azar, “there is much more interest” in these works inside Iran, leading to vendors offering “newly bought works from Sotheby’s and Christie’s” at Tehran Auction.

Reza Derakhshani’s One Golden Winter Hunt (2019) © the artist; courtesy Tehran Auction

Western auction houses are wary

“The sanctions killed things… now if people see the word ‘Iran’ they freak out,” says Nasser-Khadivi, who points to a dwindling number of Iranian works in the West. “We just couldn’t get the supply, even though there were a lot of buyers in the diaspora.”

Together with KYC (know your client) requirements, banking sanctions have made large Western auction houses wary. “We don’t want to deal with anyone who has any relationship with Iran,” says one international auction-house specialist anonymously. “For a price point of under a million dollars, it’s not worth the headache.”

Fifteen years ago, the international market created an “intersection of the diaspora and Iranians inside Iran”, says Nasser-Khadivi. “Art was the only thing we saw in our lifetime as a positive about Iran.” Now sanctions have broken that connection, but a small number of galleries and collectors have made inroads into the isolation. Hematian’s gallery Dastan, for instance, puts on “two to three international shows a year”. He says: “We want to make sure that the world benefits from the achievements of Iranian art and culture. Economics is not our biggest priority abroad.”