Of the French cultural treasures run by the Centre des Monuments Nationaux (CMN), Sainte-Chapelle, on the Île de la Cité in Paris, is the third most visited after the Arc de Triomphe and Mont Saint-Michel in Normandy. An annual 1.2 million people, of whom 80% hail from outside of France, come to marvel at this diminutive chapel’s stained-glass splendour, according to Le Monde.

From January, the 35% of those visitors who are from outside the European Union will be charged €22, compared to the EU ticket which varies, depending on the day, between €13 and €19.

When the price hike was announced in December, the president of the CMN, Marie Lavandier, told Le Monde newspaper that it remained “modest”. Referring to the higher prices already charged in high tourist season, she said that people were just as satisfied with their visits and no complaints about the prices had been registered. That led her to conclude that price hikes would only be a problem if what people were coming to see was in some way lacklustre—and no one could say that about Sainte-Chapelle.

For nearly 800 years, art historians, theologians and tourists alike have noted the resplendence with which Sainte-Chapelle overwhelms its visitors. In 1323, the French philosopher Jean de Jandun likened entering it to being “rapt to heaven”.

“One rightly imagines,” he wrote in his Treatise on the Praises of Paris, “having entered one of the most beautiful homes in paradise.”

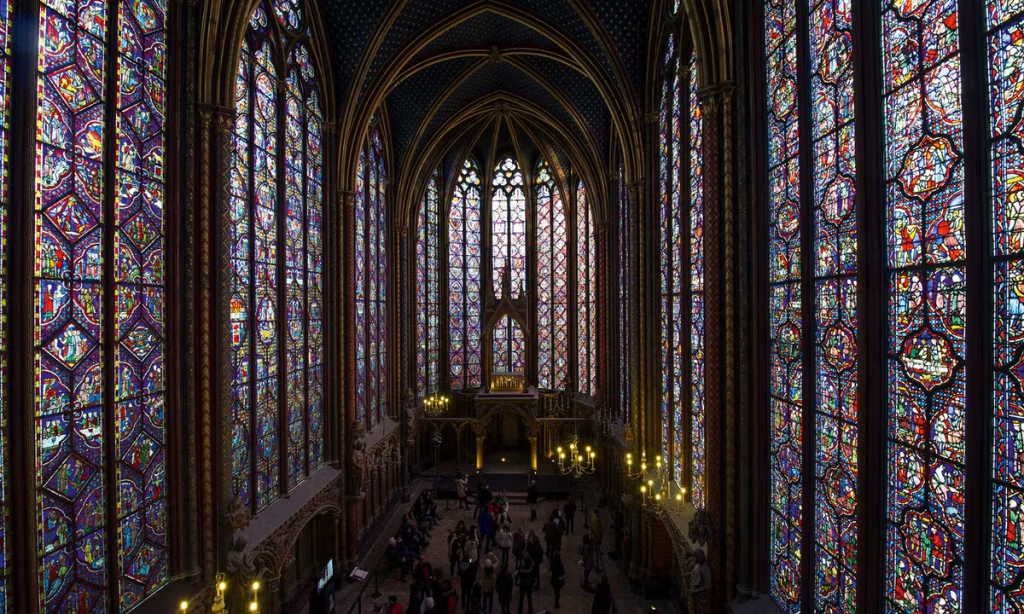

What makes it so sublime are the upper chapel’s 15 stained-glass windows—“a national treasure,” says Sylvain Michel, the chief architect and urbanist at CNM. Michel is currently overseeing an extensive, long-haul restoration project on the chapel’s windows and the stonework that supports and frames them. Due for completion in 2030, the campaign will cost a total of €21.5m, Michel says.

Soaring weightlessness

This month the team embarks on the Jeremiah and Tobias bay, which sits between the apse and the southern façade, as well as the Judith and Job bay, on the southern side of the nave. This follows the successful reinstallation, in December, of the Ezekiel bay in the apse.

These windows stand 13 metres tall around the apse and an even more impressive 15 metres along both sides of the nave. Together they count 1,113 narrative panels, separated by reinforced stone pillars so slim that the brilliant scenes they offer appear to float in mid-air, lending the entire room a sense of soaring weightlessness. Research on the exceptional 13th-century structural innovation at work shows the internal iron rods used in these pillars were sourced from as far away as Belgium.

Over the past 20 years, five of the seven apse windows, the northern façade and the western portal rose have been restored, along with stonework and sculpted elements. Because two-thirds of these windows are originals dating back to the 13th century, the vision for the chapel’s restoration has long been about more than simply fixing them.

Since the 1970s, Michel says, conservators, first at the department for regional cultural affairs and, from 2007 onwards, at the CMN, have progressively removed the historic windows to study and work on them in atelier conditions, and installed clear-glass replicas in the original casings.

Once restored, the originals are then placed a few centimetres further inside. “This guarantees that the building is sealed off from the elements and the historic windows are protected,” Michel says. As conservation protocols go, this has repeatedly proven an astute move. When hailstones the size of ping-pong balls carpeted Paris in a thick layer of ice on 3 May 2025, Michel says that the restored western rose, which bore the brunt of the storm, was unscathed. Luckily, no hail hit the Ezekiel bay on which work was only just beginning at the time.

Much like neighbouring Notre-Dame, Sainte-Chapelle was the subject of a “grande restoration” in the 19th century. Between 1837 and 1863, several architects—Félix Duban, Jean-Baptiste Lassus, Émile Boeswillwald and his son Paul Louis Boeswillwald—undertook ground-breaking conservation work. When archaeologists examined the rose above the western portal and the windows of the northern façade in the 2010s, they found that, in terms of the stained glass, those 19th-century interventions had been impressively light-handed. Of the 87 figurative panels in question, only nine had been recreated in full—all the others were the originals.

A prototype spire for Notre-Dame

It is while heading up work on Sainte-Chapelle in 1841 that Lassus met Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Two years later, they applied together to take charge of the restoration of Notre-Dame. The spire Lassus et al rebuilt for Sainte-Chapelle would go on to be a prototype for Viollet-le-Duc’s fabled design for Notre-Dame.

Both the cathedral and the chapel served political, nation-building purposes from the outset. But they did so in very different ways. When Louis IX returned to Paris in 1239 with 22 relics of the Passion—Christ’s Crown of Thorns alone had cost him over half of the French crown’s annual income—he chose to first show them to the public in Notre-Dame. He then spent inordinate sums to build the Sainte-Chapelle as a quasi-private reliquary to hold them.

Restoration work in progress

© Benjamin Gavaudo/Centre des Monuments Nationaux

Historians and pundits couch French president Emmanuel Macron’s insistence on rebuilding Notre-Dame as quickly as he did in contemporary political terms. The president of a divided nation was restoring the people’s cathedral to the people, thereby hoping to unite them.

By contrast, Sainte-Chapelle’s plodding 50-year restoration programme speaks to altogether more ancient power plays. It has not been used as a place of worship since the late 18th century, and for long periods during the intervening centuries it was closed to the public altogether. Keeping it alive, therefore, is about preserving history.

The chapel, as Michel puts it, was “wanted by the king”. While this was well before the time of Louis XIV, the assertion of divine power—the deification of the monarchy—by which the Sun King would later operate is rooted in its stained-glass magnificence. “The entirety of the nation’s history is distilled in this one monument,” Michel says.