Art

R. Crumb, I’ll Just Stand and Wring My Hands and Cry, 2025 © Robert Crumb, 2025 Courtesy the artist, Paul Morris, and David Zwirner

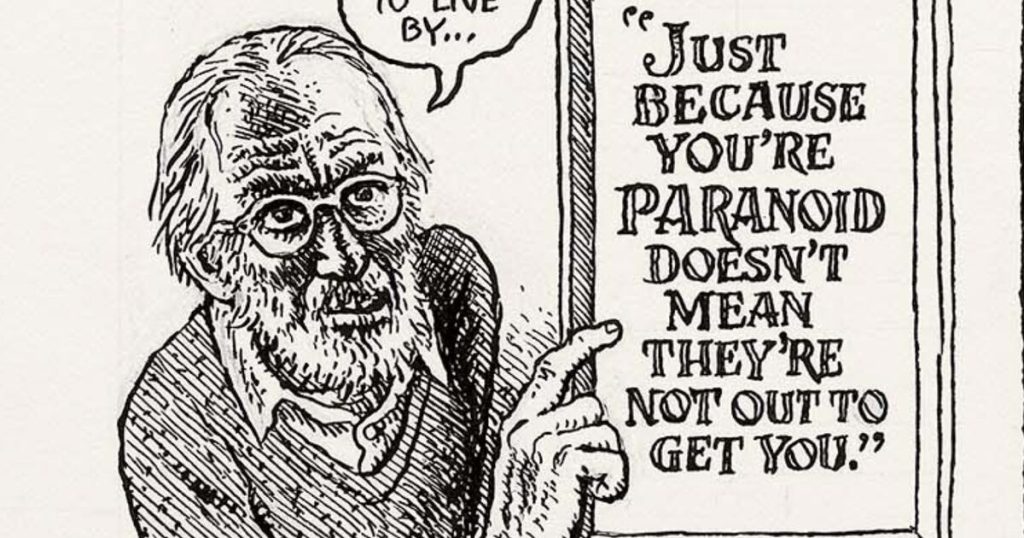

R. Crumb, Cover: Tales of Paranoia, 2025 © Robert Crumb, 2025 Courtesy the artist, Paul Morris, and David Zwirner

When 23-year-old Robert Crumb arrived in San Francisco in January 1967, he was just another aspiring cartoonist with a modest reputation in the alternative press. And yet, by the end of the following year, he had been profiled in Rolling Stone, hung out with Janis Joplin (famously drawing the cover of her classic album Cheap Thrills), and turned down invitations to collaborate with Hugh Hefner, Roger Vadim, and Jane Fonda.

The catalyst for this sudden fame was the publication of Zap Comix #1 in February 1968, which both opened up comic books as a means of serious artistic expression and helped shape the vernacular of late ’60s counterculture.

One of the few cartoonists to be embraced by the cultural establishment from early in his career, Crumb (better known as R. Crumb) has always walked a fine line between low and high art. In 1969 alone, his work was included in shows at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, an unusual level of recognition for a comic book artist at the time. Since the 1994 documentary Crumb brought him a new level of fame, his work has become a regular fixture in both museums and commercial galleries, including retrospectives at London’s Whitechapel Gallery and the Musée d’art Moderne de Paris. In 2015, the art for his controversial 2009 bestseller, The Book of Genesis, sold for $2.9 million.

This autumn, Crumb’s work returns to the Whitney, appearing alongside works by Louise Bourgeois, Dorothea Tanning, Yayoi Kusama, Claes Oldenburg, and others in “Sixties Surreal” (through January 19th), a hugely ambitious show focusing on the psychosexual, fantastical, and revolutionary tendencies in American art of the period. At the same time, David Zwirner Los Angeles presents “R. Crumb: Tales of Paranoia” (through December 20th), displaying work from the artist’s first new comic book in over 20 years which focuses on his obsessive search for meaning in an internet-addled world.

Early life

Born in Philadelphia in 1943, the young Crumb was forced to reconcile rigidly Catholic schooling with a highly dysfunctional family life marked by addiction, mental illness, and physical abuse. The experience left him with a lifelong suspicion of authority. A social misfit with little interest in the latest fads enjoyed by his classmates, he obsessively studied old newspapers, 78 rpm records, and vintage cosmetics packaging. Other inspirations included obscure funny animal comics, early MAD magazine, Disney animation, and classic 1930s cartooning like Popeye.

Crumb brought these influences to his work for American Greetings, one of the world’s largest producers of greeting cards. As Dan Nadel, co-curator of “Sixties Surreal” and author of recent biography Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life, pointed out, “By the time Zap #1 came out, he had been working as a commercial artist at a very high level for half a decade, so he really knew how to communicate and he knew how to pack in jokes and signifiers.” But it was an intense LSD trip in spring 1966 that finally allowed his trademark style to emerge. “I started getting images of these comic characters that I’d never drawn before with these big shoes and everything,” he explained in Crumb. “All the characters that I’d use for the next few years came to me during this period.”

R. Crumb, Self Portrait (Just My Normal Day), 2023 © Robert Crumb, 2023 Courtesy the artist, Paul Morris, and David Zwirner

His early stories were multi-layered, and intensely personal, often rejecting the constraints of linear storytelling. But they were also deeply scathing critiques of consumerism and the darkness lurking at the heart of the American dream. Like the painter Philip Guston (with whom he is often compared), Crumb was not afraid to offend, depicting racial stereotypes, misogyny, incest, and his own sexual fantasies in ways that many found shocking. But what made his work powerful was that it clearly reflected his own disgust and fear of what he saw within himself. As the titles of his comics—Despair (1969), Weirdo (1981–90), and Self-Loathing (1995–97)—often made clear, he knew he was part of the problem.

Artistic style

For Nadel, this combination is key to his success. “The reason his style resonated so strongly is that he was using a very traditional cartoon language that the entire baby boomer generation had grown up with, but transformed it for his own purposes…He was telling people ‘Everything’s a lie,’ but doing it with these bouncy cartoon characters.”

His style continued to evolve, the loose, cartoony illustrations of the ’60s and ’70s giving way to atmospheric brushwork in the ’80s and more densely crosshatched drawings in the ’90s and beyond. But from the very beginning his work, along with that of his fellow underground cartoonists, had made an impact on the fine art world. As Nadel pointed out, “A lot of painters at the time—Peter Saul, Roy De Forest, Jim Nutt, William T. Wiley, Robert Arneson, Judith Linhares—felt that they were part of their world.”

Robert Crumb, Burned Out, Cover for The East Village Other 5, no. 10, 1970. © Robert Crumb, 1970. Courtesy the artist, Paul Morris, and David Zwirne

Robert Crumb, Head #1, 1967. © Robert Crumb, 1967. Courtesy the artist, Paul Morris, and David Zwirner and Heritage Auctions/HA.com

Throughout these shows, his masterful penmanship and unfiltered imagination shine from every page. At the Whitney, the profile depicted in Head #1 (1967) is infested by a labyrinthine network of wires, circuits, tape recorders, and cameras. Hung alongside Lee Friedlander’s eerie photographs of television screens in motel rooms, it fizzes with sinister electrical energy, evoking the sudden incursion of new technologies into everyone’s lives, suggesting they were, almost literally, re-wiring people’s brains.

Elsewhere in “Sixties Surreal,” Burned Out (1970) is a self-portrait of the artist, brain fried, eyes protruding on stalks, with a hand wrapped around his tongue, as if he doesn’t want to see, think, or talk about anything ever again. It seems to encapsulate the mood of its time: the end of the sunny idealism of the 1960s.

“Tales of Paranoia”

In the David Zwirner exhibition, Crumb reflects on life in his eighties, addressing his anxieties about the fear and paranoia of the “post-truth” era. Are conspiracy theories “Batshit crazy or true perception—who can tell?” he asks on the cover for Tales of Paranoia (2025). As ever, though, he’s not interested in black-and-white answers, his art operating instead in an uncomfortable gray area. The autobiographical strip What is Paranoia? (2025), for example, evokes the uneasy state of not knowing—of being dimly aware of things just outside your perception—rather than offering concrete solutions.

Page from R. Crumb, I’m Afraid, 2025 © Robert Crumb, 2025 Courtesy the artist, Paul Morris, and David Zwirner

Page from R. Crumb, What is Paranoia?, 2025 © Robert Crumb, 2025 Courtesy the artist, Paul Morris, and David Zwirner

In I’m Afraid! (2025), he depicts himself waking in the middle of the night, shrouded in a dark inky void, filled with fear of 5G, the panel borders and word balloons quivering around him conjuring a state of extreme unease. In two related strips, God Help Me and I’ll Just Stand and Wring My Hands and Cry (both 2025), the aging cartoonist, frail and hunched, with a white beard and a face etched with lines, confronts his creator, pleading for hints about the true nature of humanity, only to be fobbed off with a few New Age banalities and some tips on breathing techniques.

Taken together, both exhibitions show an artist who, over six decades, has continued to refine his craft, while remaining suspicious of the fame he has achieved and always looking to understand his place in the world. “He’s a searcher and always has been,” Nadel concluded, noting his influence on the art establishment. “It’s important that his drawings find their way into these sorts of shows. He’s a very important part of American art history.”