“Photographers are a different breed of human being,” Christian Caujolle once said. “Not the ones who are producers of images but those who are able to propose a different point of view. The ones whose perspective is not about reproduction but interpretation, using such a strange and specific tool as photography. And always with a tension between realism and fantasy.”

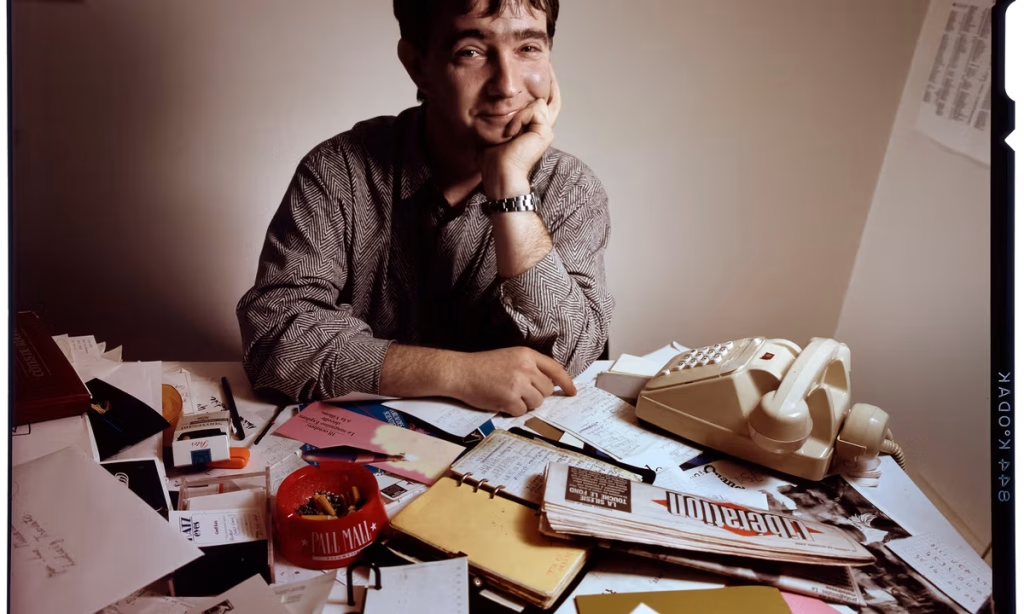

The founder of the influential Agence Vu, who died in Tarbes, France, on 20 October, aged 72, was a seminal figure in French photography, and by extension, an immense influence on how the medium is perceived around the world. Starting out as a critic and then photography director at one of France’s leading newspapers, then setting up Vu as an agency and later a gallery, he was a prolific writer and curator known for his energetic support of young talent, and an unyielding commitment to the assertion of the photographer as an auteur.

“My passion for photography probably comes from the fact that, when I was a child, I had no access at all to visual culture,” Caujolle once said. “It has fuelled me with curiosity.” He was born in 1953 and grew up on his grandparents’ farm in a small village in south-west France. He studied in nearby Toulouse for a year, where his encounters with Jean Dieuzaide, the founder of the Château d’Eau gallery, were transformative, encountering photography as an art form.

At the centre of Parisian intellectual life

At the École Normale Supérieure in Paris he studied modern literature, became friends with his teachers Michel Foucault and Roland Barthes, and prepared a thesis with Pierre Bourdieu. He worked with Foucault after university, including research for Je Suis Pierre Rivière, which was adapted into a book and film, and started as a journalist at Libération, the leftist newspaper co-founded and initially edited by Jean-Paul Sartre in 1973 in the wake of the 1968 protests. He wrote about art and literature, and increasingly turned his attention to photography, spending most Saturdays at the gallery of Agathe Gaillard in Paris’s Marais district, the first gallery in France exclusively devoted to the medium. It was here, in the late 1970s, that he met many of the greats of post-war French photography, such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Doisneau and Brassaï, as well as visitors from abroad, including André Kertész, Bill Brandt and Larry Clark.

He and Hervé Guibert at Le Monde were an integral part of a transformative time for photography’s recognition and status in France. “Christian and his peers really trained a generation to be interested in photography,” says François Hébel, a contemporary of Caujolle best known for his leadership at the Les Rencontres d’Arles photo festival. Then, in 1981, when Libération was relaunched, he became the director of photography, in charge of the visual content of the daily newspaper.

“He changed the way photography was used in newspapers,” says Hébel. He would commission unknown photographers, and he gave established names surprising assignments. William Klein was sent to cover Pope Jean Paul II’s visit to Lourdes in 1980, because Caujolle wanted “an irreverent eye”. Raymond Depardon was commissioned to send a picture per day to appear in the newspaper’s foreign affairs pages, accompanied by a diaristic text about his mood. Sophie Calle’s The Address Book ran as a summer column. “Many photographers owe their careers to him because of his willingness to take chances and his incredible eye.”

Agence Vu, which Caujolle described as “photographers’ agency, not a photo agency”, emerged as a special project in a small office at the newspaper. He left Libération to launch Vu in 1986, challenging the traditional news photo agency model by enrolling photographers who brought a more subjective approach. It was enormously influential, but “he wasn’t a natural entrepreneur”, says Hébel, who was the director of Magnum Photos in Paris during roughly the same period.

Caujolle was perhaps at the height of his influence when he fulfilled a long-held dream to open an exhibition space. Galerie Vu opened in 1997 with Caujolle as its artistic director. He and Vu both became associated with an introspective, stream-of-consciousness type of photography exemplified by Antoine d’Agata and Michael Ackerman. “Those were two he really pushed,” says Hébel. “He also supported photographers like Anders Petersen, Denis Darzacq and [many others]. The work became darker, more introspective. He was always ahead, sensing what was next… He had a nose for discovery.”

‘He had faith in intuition’

The Swedish photographer J.H. Engström was one such “discovery”. “When Christian was in Stockholm, I went to meet him. I laid out all the prints for [the photographic diary] Trying to Dance. The whole floor of the lobby was covered. He looked at them and said, very simply but with great conviction, ‘This has to be exhibited.’ And right there, on the spot, he proposed an exhibition at Galerie Vu.” What impressed him about Caujolle’s approach in the years that followed that first encounter? “He was an intellectual, but he went beyond theory — and very few people do that. Theory and intellectual patterns are like crutches for many in this business… [but] he had faith in intuition.”

Photography was for him about following what you believe… taking adventures inside yourself

Anders Petersen, photographer

Engström’s teacher, Anders Petersen, recalls a similar encounter that led him to also join Vu in the early 2000s, beginning a long friendship and working partnership: “[he] was absolutely honest, but also warm, generous and full of solidarity. You felt part of his family… Photography, for him, was about life and following what you believe… Taking adventures inside yourself. That’s how he lived too.”

In the same year that Galerie Vu opened, Caujolle was the guest director of Les Rencontres d’Arles, and he repeated the role at smaller photo festivals in the Netherlands, the Basque region and in Sweden, before setting up his own, Phnom Penh Photo, in 2008. Monica Allende, a London-based curator and festival director who took over from him at both GetxoPhoto and Landskrona Foto, says he was a visionary, especially in how he conceptualised photography in public spaces. “I saw his genius up close. He had this way of understanding the local culture and making it central,” she says. “In Phnom Penh, he projected images onto boats that drifted along the river, turning the city’s daily life into part of the exhibition. It was extraordinary, and so thoughtful, so respectful.”

Caujolle curated countless small shows platforming emerging photographers, but there were major exhibitions also: the Lithuanian Pavilion at the 2003 Venice Biennale, Gérard Rondeau at the Grand Palais in Paris, and Things as They Are: Photojournalism in Context Since 1955, which toured globally. Throughout, he always wrote, producing dozens of monographs, prefaces, catalogues and, in 2007, a kind of memoir of his encounters with photography, titled Circonstances Particulières (Special circumstances) presented in two volumes by Actes Sud.

In January 2010 he was appointed Officer of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. Ten years later, he was appointed artistic adviser at Galerie du Château d’Eau, where he saw his first photography exhibition 50 years earlier. Then, in 2024, the year before he lost his battle with cancer, Caujolle was implicated in an accusation of sexual assault in the 1980s. Caujolle vigorously denied the allegations and the investigation remains ongoing. In a statement, Les Rencontres d’Arles celebrated Caujolle’s “immense contribution to the world of photography”, but acknowledged the accusations by adding: “His passing leaves the world of photography suspended between emotion, gratitude and questioning.”

Christian Caujolle, born Sissonne, Hauts-de-France, 26 February 1953; director Agence Vu 1986-1998, artistic director Galerie Vu 1998-2007; died Tarbes, 20 October 2025