Sylvio Perlstein was born in Antwerp in 1931, and died there at the age of 94, but he lived a circuitous and peripatetic life which joined the co-ordinates for some of the most exciting transatlantic networks in modern art. Perlstein was one of the last of the great collectors of 20th-century avant-garde art who lived through many of its defining moments and was friends with some of its foremost stars.

Not all of Perlstein’s travels were made at liberty, though. He was from the third generation of a leading gem-cutting dynasty in the diamond capital of the world but, in 1939, with the Nazis on the march into the Low Countries, the infant Sylvain Perlstein fled with his Jewish family to Brazil, where he reinvented himself as “Sylvio”. Later in life, he would think, and define ideas, in Portuguese. The central question for any work he looked to buy was always, “Is it esquisito?” For Perlstein, it was, he said, a “word that doesn’t mean ‘exquisite’, or ‘nice’ or ‘beautiful’, like exquis in French, but ‘weird’, ‘strange’, ‘different’.” In Paris, Perlstein earned the nickname “’squisito” himself.

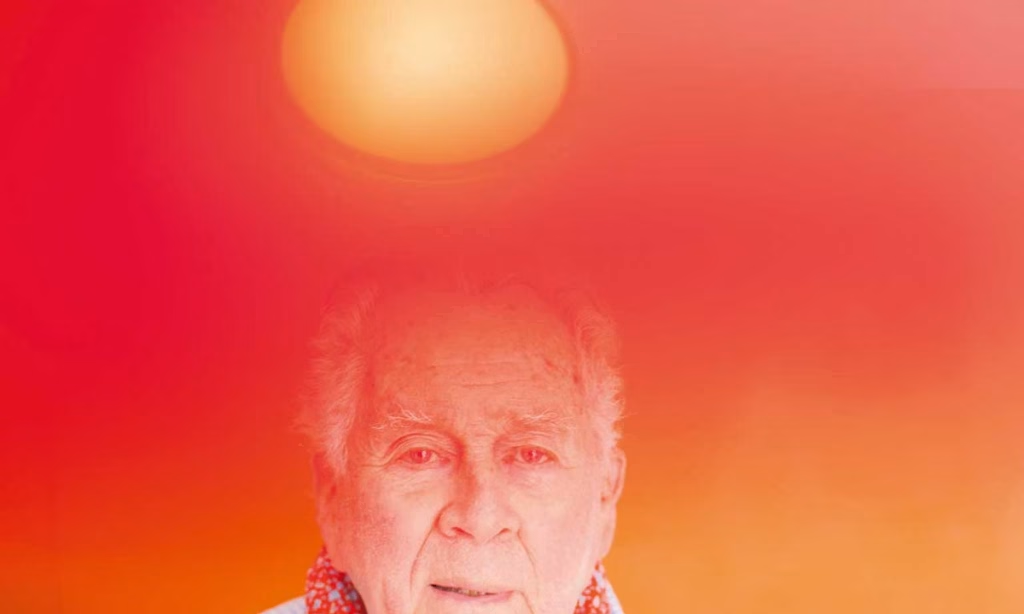

Ask Sylvio which he prefers among his collection and the half-serious, half-amused reply is, all of them

While Perlstein would later dismiss the grandiose idea of “a collection”, the first work he bought was from a small store selling flowers by Copacabana beach in Rio, around the corner from where he lived. He was struck by a wonderful and weird painting on the side of a vitrine. He went back and back, all the time pestering the florist to let him have the painting: “She couldn’t understand why I wanted to buy it.” Eventually, the adolescent Perlstein managed to persuade her and so began his lifelong knack of persuading people—often artists, straight from the studio floor—to part with their treasures.

‘Things that I liked because they were different’

While Perlstein begrudgingly returned to Antwerp after the war to take over the family business, his heart was set on immersing himself in art. He sought out the chicest galleries, such as Wide White Space, and drank with the scene that congregated around the bohemian Plaatsnijdersstraat—a group which included Yves Klein—until two and three in the morning. It came as a surprise to him that his hometown proved to be a boon for his early collecting. It was in Antwerp (and on regular visits to Brussels) that he acquired works by several important Belgian Surrealists and conceptual artists, including E.L.T. Mesens, Marcel Broodthaers and René Magritte. Perlstein honed his talents for persuading reluctant sellers, but he was not seeking to establish a collection as such, only gather, in his words, “things that I liked because they were different”.

Many of his collecting interests began with chance encounters. In 1969, Perlstein was travelling in the south of France when he and a friend spent a drizzly summer’s afternoon driving to an exhibition at Galerie Alphonse Chave in Vence with the provocative title of Les Invendables par Man Ray (“The Unsellables by Man Ray”). Perlstein would have seen that as a challenge. When they arrived, the American photographer was louchely leaning on the entrance door. He and Perlstein struck up a conversation, and the Belgian bought a few gouaches and watercolours. It was the start of a significant friendship for them both. Perlstein became one of Ray’s most important collectors and was obsessed by seeing his “rayographs” up close on frequent visits to Paris. Perlstein eventually kept an apartment in the City of Light and, at the end of his life, had a wall of 100 photographs by Ray, which included a collaboration with Pablo Picasso: Hands of Yvonne Zervos (1937).

In the 1970s, Perlstein’s diamond business took him to New York, where he immersed himself in the underground club scene centred around Max’s Kansas City. “All the artists were there,” he said. “Everything moved from Europe to New York back then, Pop Art and Minimal Art were starting, with Sol LeWitt and the others.” Everyone hung out, and very few of the downtown artists had any money or success. Perlstein became friends with Diane Arbus, Robert Ryman, Hanne Darboven, all “artists… nice people… interesting people”. He maintained an apartment on the Upper West Side and became one of the most ardent supporters of conceptual art while never allowing his collection to become too much of one thing. He was enthusiastic about neon installations and bought works by Dan Flavin and Bruce Nauman. He championed “difficult” artists like Andres Serrano when most collectors wouldn’t touch their work. He loved Ed Ruscha. He cajoled an elderly Hannah Höch into selling some of her early Dadaist works. But Perlstein was never motivated by the strategies of calculated acquisition that animates so many collectors. He discovered and spent the rest of his life with works that were introduced to him in accidental discussions and late-night conversations. He was interested, above all, in art that was strange and unique, that felt close to life.

Perlstein’s celebrated collection has been the subject of several exhibitions in recent years by commercial galleries and public institutions. In 2019, Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong staged A Luta Continua, which took its title from the South African artist Thomas Mulcaire’s eponymous neon sculpture and translates from Portuguese as “the struggle continues”. Curated by David Rosenberg, the exhibition was designed to testify to “the power of connoisseurship and collecting as a talent, an art in itself”. In 2021, the Tel Aviv Museum of Art presented the exhibition Hey! Did you know that Art does not exist… of more than 100 works from Perlstein’s “intensely personal” collection, which traced “artists and trends that have defined the avant-garde, complex, and experimental nature of twentieth-century art” and included luminaries from Roy Lichtenstein to Jean-Michel Basquiat and Brice Marden to Ruscha and Cy Twombly.

Perlstein will be remembered for his self-deprecating but sardonic wit and his genuine enthusiasm for the ineffably “esquisito”, as much, it seems, as the contents of his collection. “Ask Sylvio which [ones] he prefers among the hundreds of works making up his collection and the half-serious, half-amused reply is, all of them; every one represents its own kind of trip artward, and its own way of tasting and appreciating,” the curator David Rosenberg observed. “Taken together they add up to the inexplicable weirdness that is art as he sees it.”

Above all, Perlstein embodied that rare thing these days: a collector who cared not a jot for how his possessions would fare in the fluctuations of market appreciation (or depreciation). He could never understand why a collector would buy a work in spring and sell it by winter. It just didn’t make sense to him. For Perlstein, his collection was “lively… something different”, a word he used continually for the works he sought. It was certainly not “art that can be described as dark or sad” but, in words that ring just as true for his cosmopolitan joie de vivre, “colourful” and “joyful”. Or, perhaps more accurately, “esquisito”.

Sylvain (Sylvio) Perlstein; born Antwerp 1931; died Antwerp 6 August 2025