Among the prominent presentations at this year’s Paris Photo was one by the MUUS Collection which traced a lineage of artistic evolution across two generations of photographers. Looking Out, Looking In: Larry Fink and Rosalind Fox Solomon with Lisette Model placed the work of Fink (1941-2023) and Solomon (1930-2025), whose archives are owned by MUUS, in dialogue with that of their teacher, the pioneering Austrian-born photographer Lisette Model (1901-83).

The MUUS Collection, which is a partner of the fair, is a US-based organisation that acquires and develops photographic archives. Since its founding by Michael W. Sonnenfeldt, MUUS has focused on acquiring the estates of under-examined artists—among them Fink’s and Solomon’s, which were acquired in 2024 and 2021 respectively—and transforming them through preservation, research, exhibitions and publications. Its holdings also include Deborah Turbeville, Alfred Wertheimer and André de Dienes. MUUS does not own any of Model’s work, including the prints on display in this exhibition; they were featured thanks to the French gallery baudoin lebon in a collaborative effort to highlight the importance of the photographer’s work as an image-maker and teacher.

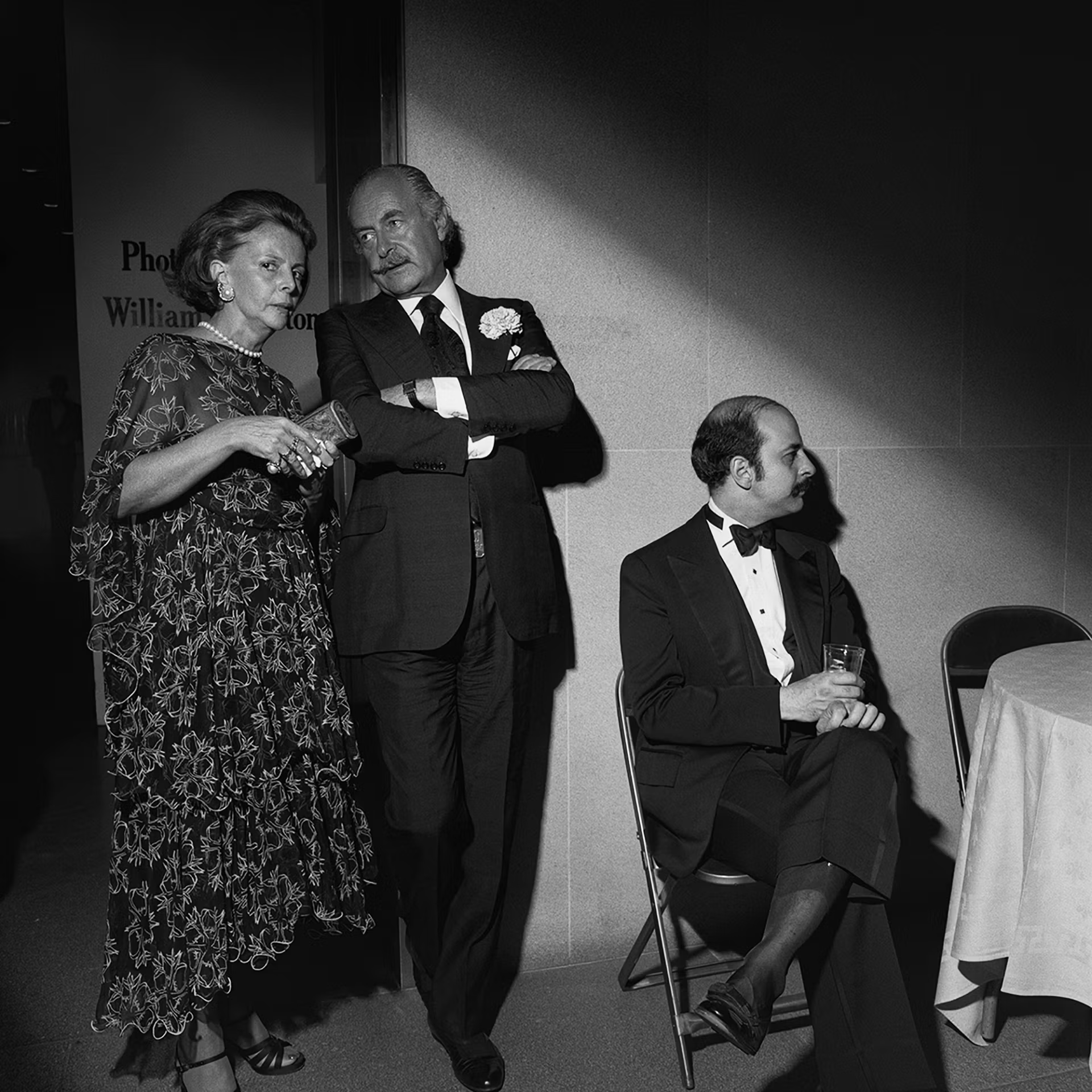

A photo of Lisette Model herself at Brassai’s Marlborough Gallery opening in New York by Rosalind Fox Solomon (1976) © Rosalind Fox Solomon / MUUS Collection

Anne E. Havinga, the curator of photography at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, organised the presentation. She sees the exhibition as an opportunity to underscore the pedagogical as well as the aesthetic legacies of Model, who taught at New York’s New School for Social Research from 1951 and profoundly shaped the outlook of her students. “Model’s teaching prioritised personal vision and creative independence,” Havinga says. “Through intense personal mentorship, she transmitted her deep fascination with human psychology and the diversity of human experience to her students.”

Model believed that “photography starts with the projection of the photographer, his understanding of life and himself into the picture”. Her lessons were philosophical rather than technical. That approach is made visible in the ways her students developed. Fink, best known for his series documenting parties, political events and jazz clubs, sought to capture what he called “the breath and life” of his subjects. He credited Model with teaching him to pursue the “energy, the pulse of things”.

Larry Fink’s Benefit, The Museum of Modern Art New York, NY, June 1976 (1976) © Larry Fink / MUUS Collection

Solomon, who only began photographing in her late 30s, also found in Model a teacher who encouraged her to face her own anxieties and sensibilities. Solomon’s sometimes unsettling portraits reveal what she described as “what is most deeply felt yet often unspoken”. Her death earlier this year lends the Paris Photo presentation an elegiac tone: the exhibition is dedicated in part to her memory.

Each of these photographers used the camera to pursue a form of social inquiry. Havinga says that Model “profoundly shaped her students, giving them the confidence to photograph fearlessly. But those students in turn developed independent voices, ensuring that her teachings were refracted into new contexts.”

The presentation comes amid a broader resurgence of attention to Model. Alongside the MUUS display in Paris, Vienna’s Albertina museum is staging a major exhibition of her work, and the London-based publisher Mack is preparing a new volume this autumn.

For MUUS, showing at Paris Photo is part of a deliberate strategy to embed its holdings in the wider public consciousness. It is also a reminder that archives are not only repositories of the past but also active sites of interpretation. In Paris, MUUS’s stand offered visitors a chance to see how a teacher’s philosophy echoed through the work of two of her most gifted students, and how those legacies are being shaped again for the next generation of lens-based artists.