As director of artist programs at the Joan Mitchell Foundation, Solana Chehtman oversees the foundation’s programs related to artists’ legacies. As Mitchell stipulated before her death in 1992, the foundation has devoted attention to the needs of other artists via grants, fellowships, and convenings focused on creating opportunities and teaching artists how to think about their future, both during their lives and after. Prior to working at the Mitchell Foundation, Chehtman was the director of creative practice and social impact for The Shed in New York.

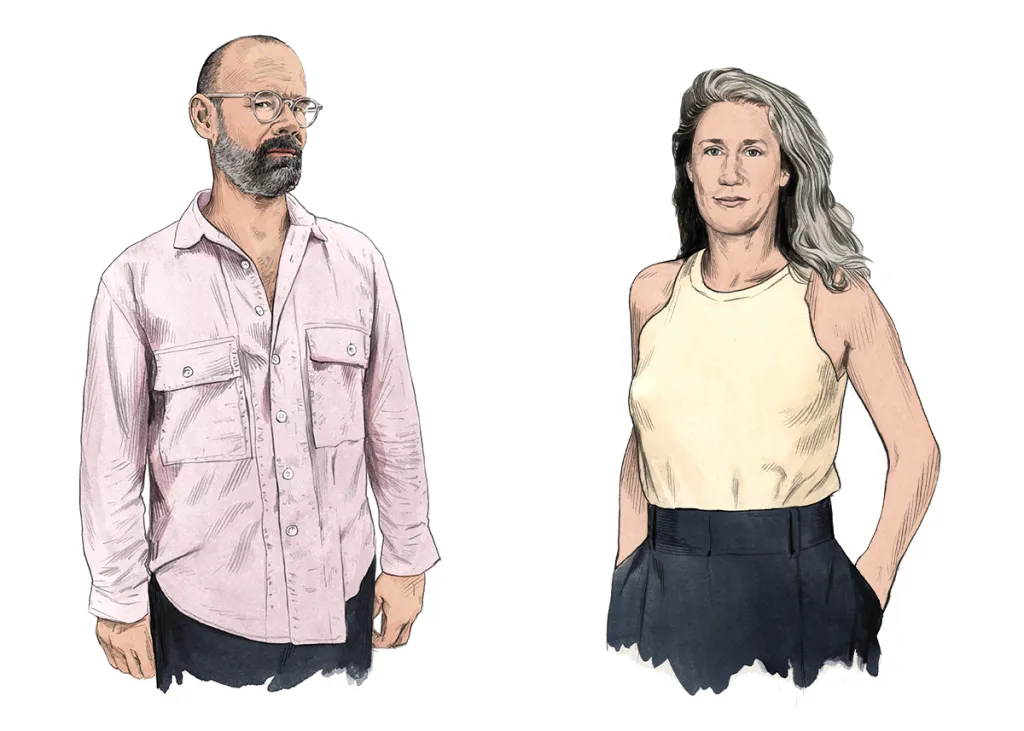

Chris Sharp opened his eponymous gallery in Los Angeles in 2021 and co-represents—with Jacky Strenz in Frankfurt, Germany—the estate of Lin May Saeed, a sculptor who died in 2023 at the age of 50. He has shown Saeed’s work since 2017 and continues to, as he endeavors to keep her legacy alive in an international art world with differing degrees of familiarity with her work. Sharp has also started working with the estate of Deborah Hanson Murphy, a painter who died in her 80s in 2018. Prior to his LA venture, Sharp operated the Mexico City gallery Lulu from 2013 to 2023.

ARTnews spoke with Chehtman and Sharp this summer about the challenges and opportunities related to artists’ estates, how living artists can start thinking about their legacy, and other issues related to the prospects of finite life and infinite futures.

Artist Marcos Dimas (right) working with legacy specialist Alexandra Unthank as part of the Joan Mitchell Foundation’s CALL program in 2018.

Photo Megan Pasko

ARTnews: Solana, the Joan Mitchell Foundation does a lot of work pertaining to more than just Joan Mitchell. How do you characterize the range of work the foundation undertakes, and why is that important in the context of Joan Mitchell?

Solana Chehtman: Joan Mitchell was very specific in her will, she defined working with other artists as a mission. We’re very privileged in that sense, because a lot of artists did not get to do that before foundations got created in their names. We have two arms: One has to do with preserving her legacy, and the other is a programs team. We gave grants—$25,000 to 25 artists a year—for many years. Then, in 2001, we shifted to a five-year fellowship for artists, for which we provide unrestricted funding, community-building, and intentional support. Some people call it professional development, but we think about it as more like personal advancement. We always say that we’re a foundation from one artist to the many. Artists are represented on our board, in our staff, in our selection processes. One artist board member once said, “We’re doing all this work around Mitchell’s legacy, but what’s going to happen to our work? How do we ensure that our work doesn’t end up in the dumpster?” That’s how our program Creating a Living Legacy (CALL) started in 2007.

ARTnews: Chris, you started working on the estate of Lin May Saeed when she passed away at the age of 50. How much or little planning had you done with Saeed prior to her passing? Were you able to have conversations about the future of her work and her legacy?

Chris Sharp: I co-represent the estate of Lin May Saeed with Jacky Strenz in Frankfurt. I ran a space in Mexico City called Lulu, and we did a show in 2017—that’s when we developed a relationship. When I opened my gallery in Los Angeles in 2021, I asked her to join the program, and really soon after that she was diagnosed with brain cancer. She passed away in 2023. Jacky had been with Lin for a long time, and they managed to do a lot of estate planning in the two years from when she was diagnosed until she died. It was both a blessing and a curse that she didn’t go suddenly. They were able to think about a lot of different things, like making editions and Lin signing off on them. That wasn’t about creating income: Lin worked slowly, and there wasn’t much work, so it was about making the work accessible and creating the potential for visibility.

View of Lin May Saeed’s exhibition “The Snow Falls Slowly in Paradise. A Dialogue with Renée Sintenis,” 2023, at

the Georg Kolbe Museum, Berlin.

Photo Enrich Duch

ARTnews: How does the co-representation of Saeed’s estate work?

Sharp: My role is primarily representation in the United States. I did Lin’s last show while she was alive. She was too sick to travel for that. I recently did a solo presentation with her at Post-Fair in Los Angeles, and we secured a solo show on the back of that at Anton Kern Gallery in New York. Lin has a lot more visibility in Europe. She’s in great collections in Italy and France, and she’s starting to enter important collections in Germany. She’s got this incredible support A Call to Action Artist Marcos Dimas (right) working with legacy specialist Alexandra Unthank as part of the Joan Mitchell Foundation’s CALL program in 2018. network, but here in the US, she’s still pretty unknown. I’m doing my best to change that.

ARTnews: Did you have any prior experience thinking about estate planning yourself, or was it a new subject for you?

Sharp: It was new for all of us, and it started with really basic stuff. I still feel like a newcomer in this situation. When Lin passed, I reached out to a close friend of mine: Wendy Olsoff from P·P·O·W gallery in New York. She has a handful of important estates, including Martin Wong’s, so I reached out and asked what we should do. She brought up some really good points—like make an Instagram account. That seems like a no-brainer, but it all starts with little things like that. Another project that Jacky and I have discussed is making a website with a complete archive of all the work. These basic things have been really new to me, in terms of communication and promulgation and trying to ensure the continued visibility of artists after their death. I’m really learning on the job, as it were.

ARTnews: Solana, as you mentioned, Creating a Living Legacy was established in 2007. What kinds of issues does that program deal with?

Chehtman: A lot of what Chris shared is what we have been seeing when artists pass away, and the family or gallery or peers don’t know where to start. Because we support artists directly, we always want to give them the opportunity to have agency and a voice for how that narrative is going to be crafted. What do they want the story to be? What works do they want to preserve? It was very much about giving artists the tools to do that. Originally, while giving grants, we gave artists money and convened them so they could learn from each other. But we realized they didn’t even know where to start. We started hiring and training what we call legacy specialists, who are younger artists with better technological capacities, and pairing them with older artists to talk about how to inventory and document their work. We had a couple of cases at the beginning, from Jaune Quick-to-See Smith to Mel Chin. Jaune reflected afterward that her career survey at the Whitney Museum had a lot to do with this work. She realized just how generative the process of looking back could be.

After some years of doing that, we wanted to share more broadly what we’d learned from working hand-in-hand with artists. We moved to publishing workbooks that are free and accessible on our website. It’s great that artists have access to this material, but there’s also the question: How are they using it? There’s access to a lot of information, but that’s not always useful enough. Our position lately—and this has been an iterative process of learning from artists—is that we want artists to have agency, yes, but they cannot bear the responsibility alone. As a foundation that has the possibility to be a bridge, how can we ensure that there is more institutional awareness of the importance of this, specifically in this moment of cultural erasure and also the expansion of the art world? There’s a lot of processes happening in parallel, so our intention lately has been more about how we can move this work forward, and what does that need to look like in terms of being sustainable and scalable? We won’t ever be able to work with everyone. There is an ocean of need for this type of support. But can we convince other foundations or other granters to support this work? Can we work with collecting and non-collecting institutions, residencies, and universities that can be our partners in providing artists this information? As people get older, in particular those who are not commercially successful, how can they learn how to do all this? That’s what CALL exists for.

Chris Sharp in his eponymous Los Angeles gallery.

Photo Moë Wakai

ARTnews: Chris, you mentioned awareness of Lin May Saeed’s being more prevalent in Europe than in the US. Are there different questions that arise in different places related to cultivating her legacy?

Sharp: I feel as if, in America, we’re having a very specific conversation around art, and identity always seems to be its starting point. Lin was an animal activist—that’s a part of her identity, but that’s not what the work is about entirely. In a sense it’s made it harder, even though I think the issues she’s discussing in her work are universal, like animal rights, the dignity of other species, and considering a more equalrights- minded grounding.

My investment and commitment to the work is based on the belief that Lin was one of the most important sculptors of her generation, and my desire to create more visibility and discussion around that in the US. One thing I can say is that, despite the internet, social media, and so on, conversations tend to be regional. The conversation that’s happening in LA is different from the conversation in New York, and the conversation in Mexico City is totally different from that. When you work with an artist like Lin, you realize that. I lived in Europe for 10 years, so I have a familiarity with that. But you can try to bring a sense of context somewhere else and people could say, “This isn’t important to us here—we’re thinking about other issues.” There’s something frustrating but also affirmative about that.

ARTnews: Jacky Strenz brought some of Lin’s work to Art Basel this year. How was the response to that

Sharp: It went really well. I’m happy to report that sales were strong. I was in Basel doing the Liste fair with a different artist, so I was on the ground, and a lot of people came up to me saying that Jacky’s was the best booth in the main fair. It was really gratifying to hear that. Lin had a good career before she died. She had really strong supporters, like Chus Martínez, an incredible Spanish curator who helped get her work in great collections like Castello di Rivoli in Turin. Lin had a fair amount going on. We were all anxious when we found out she was dying, and there was a lot of anxiety around [the possibility of] her disappearing. But the level of interest since she died has been incredible. In many ways, she’s much more well-known now than she was before. At times it’s hard not to be cynical about that, I have to say. But in the case of Lin, I don’t really have a right to be cynical because she’s still very much an institutional artist. There’s no speculation or secondarymarket dealing. But sales are happening, probably more so than when Lin was alive. In some ways it’s frustrating that it took this to launch her into a different stratosphere of visibility, but it’s also really gratifying.

ARTnews: Given the death of the artist and the scarcity of the work available, how do you handle pricing responsibly and think about that in terms of sustaining her market over time?

Sharp: Lin was primarily known for working in Styrofoam, and collectors do not love Styrofoam as a material. But she was committed to it for formal and ideological reasons, which are very critical. Toward the end of her life, she started working in bronze. She had eschewed traditional noble sculptural materials like bronze, wood, and marble, but she was invited to do some commissions and started working with bronze so she could have work outdoors. Basically, all the Styrofoam works are earmarked for institutions, and the prices reflect that. They aren’t inexpensive. That’s something that reflects the scarcity, and is meant to ensure that everything keeps going. The bronze works are in editions, and those can be sold privately. That’s one distinction we’ve made.

ARTnews: Solana, from your perspective how much do estate-planning questions change depending on location, in terms of countries or other designations?

Chehtman: It’s interesting because, even within the US, there are legal issues that are different state by state. Artists who have studios and work in different states can have complications. And estate laws can be very different between the US and other places. In Argentina, where I’m from, the questions are different. What is reflected in this is that the main problem with [estate-planning] is that it’s so case by case. Every single person has a different circumstance or situation, and they need something different, which makes it hard to support and to guide—and it makes it expensive. You always need a lawyer, an appraiser, and so on. These things make it hard to systematize.

Deborah Hanson Murphy: Variation 253, 1984–86.

Courtesy the Estate of Deborah Hanson-Murphy

ARTnews: Chris, you recently started working on the estate of Deborah Hanson Murphy, a painter who died in 2018 in her 80s, and are planning a show for her at your gallery next spring. She wasn’t well-known in her time, and her work is from a different era. How does working with her legacy differ from that of a more contemporary artist, like Saeed?

Sharp: It’s hugely different. I didn’t even know that Deborah Hanson Murphy’s art existed. She rarely exhibited in her lifetime, but she was totally serious about her work. She had systems for how she created her work. What’s exciting about her is that she was from Stockton, so it makes sense to exhibit her in California and reintroduce—or introduce, actually—her to the region where she’s from. But it’s two totally different things, and I think I’m going to have to consult the Joan Mitchell Foundation website and download all the materials, because for this I’m really starting from scratch.

ARTnews: Solana, given the wealth of materials available and all the complicated issues, what are the most basic, elemental things to think about at the start?

Chehtman: In our documentation guide there’s a great first chapter on planning. But for some low-hanging fruit: Definitely always do an oral history with the artist if possible. There’s something about recording their voice and the way they want to be remembered that is very key. The second most-important step has to do with documenting and inventorying work, and creating a map for work to be found. Then also ensuring, in this moment of climate change, that the work is properly stored and safeguarded, in the case of catastrophe. Then, if possible, working on a will to define who is going to take care of the work.

Something we talk a lot about with artists is that there are practical matters but also a feelings part to this as well. Artists find this all very hard to do in general, but who can you trust? How do you want your work to be carried on? And who wants to accept that task? It’s not easy. If the artist has children, not all children want to do it.

Another piece that is key for artists is thinking about what work they want to save. The same thing goes for their archives and their papers. We’re in a moment of lack of capacity and wondering about the sustainability of both digital and physical archives. If you cannot save everything, think about pieces that were milestones— that marked a new series, or a new exploration—and make sure that you keep those. Also, do you want to donate archival materials? Do you want to sell them? Can you sell them? Not everyone can, and not everyone has a gallery willing to go in partnership to do that. Also, even donations are not easy. If you want to donate archives to your alma mater, they might not be able to take them because they need funding to ensure care of them into the future.

ARTnews: Chris, as a gallerist how much do you think about archives?

Sharp: We have a small archive at the gallery, and that’s something I’ve been thinking about. A colleague recently made me aware of the importance of having a paper archive, even if there is a digital counterpart, because things change. But I have a question for Solana about the idea of emphasizing the importance of oral history. I’m thinking we should start considering this, but it’s tricky as a dealer. How do I go to an older artist and say, “We should maybe start discussing some of these issues …”?

Chehtman: You don’t need to be old to do an oral history. Actually, it’s amazing to have oral histories of artists throughout their lives. One of our partners is the Institute of American Indian Arts. They do oral histories with their residents who are emerging artists. For another example, one of our fellows, Rupy C. Tut, says that for her work there’s a lot of cultural specificity, and she wants to develop the language with which she wants institutions to represent her work. For her, doing an oral history is key, because she wants to create that language for others. It’s not just about artists feeling old—it’s more like, “Let’s do an oral history now, and maybe we do another one in 10 years.”

Sharp: That’s good and useful. It’s weird: I’ve never had this kind of discussion before.

Chehtman: We’ve been talking with every generation, and usually when an artist gets to 50, they get to that moment where mentors and parents start passing away. Sometimes artists realize themselves that this is something they need to think about. But it depends on each individual person. There are artists who are very against thinking about this, who say, “I want to think about the future—what’s coming next.” Some others are in survival mode: “I can’t do it—I need to work on the next show or my next residency. I don’t have the stability to even think about that or engage in a process like this.” But I think it’s good for all of us, from whatever perspective, to be thinking about this. You can pass away at any age. Sam Gordon from Gordon Robichaux gallery works with the estate of Jenni Crain, who was 30 when she passed away during the pandemic.

ARTnews: Solana, you mentioned that making a market isn’t as easy for all artists. What are other modes of funding that artists or people handling estates can look to?

Chehtman: We try to encourage younger artists, as they put away a little money for their retirement, to put something away for their legacy. Some of our fellows are buying property to make sure they will have a place to store their work. A lot of opportunities have to do with collaborating with organizations. It’s very hard to selffund for this, particularly for those who are not commercially successful. The one key problem with this is funding—because there is very little available.

The Joan Mitchell Foundation’s Creating Future Memory conference, which featured a

conversation between artist Amalia Mesa-Bains and Josh T. Franco.

Photo Heather Cromartie

ARTnews: How are you thinking of support differently given the changing nature of arts funding? It feels a lot different now from even just a couple years ago.

Chehtman: When I started at the foundation in 2022, my first inclination was that I was sure there were other people doing this. Then, I realized there weren’t. There are archives, initiatives, and curators finding ways to hack the system. But it’s very much individuals within institutions who are pushing, and the institutions are not necessarily buying in. With the foundation’s executive director, Christa Blatchford, I put together an advisory council that organized a convening called “Creating Future Memory” this past May. There were 150 people in attendance, with more than 60 percent not from New York. That was intentional because, as Chris was saying, a lot of these conversations are regional. This is a lot about place-making and thinking about local artists in different places. Why are we looking at the same 10 artists nationally, and not looking at local artists?

ARTnews: What were some of the main takeaways from the conference?

Chehtman: The idea came from Teresita Fernández’s US Latinx Arts Futures Symposium in 2016. She partnered with the Ford Foundation [around the idea that] Latinx art is not considered part of “American art” or “Latin American art”—it’s in this position where no one is giving it visibility or support. It focused on conversations with institutional representatives and artists in the same room having to come to terms with it as an issue. Out of that came grants for artists and for curators and new positions, like Marcela Guerrero’s [curatorial] position at the Whitney Museum. I always say that conference and PST: LA/LA were like a before and after for the Latinx art community in terms of visibility.

In putting together “Creating Future Memory,” we invited gallerists, institutional representatives, archivists, and people in between. We wanted to map and give visibility to different models. One of the main takeaways was that this work has been done in different ways by different communities. That was a very big point that was made, especially by Indigenous artists. Dyani White Hawk, for example, talked about how there are practices and a spectrum of different ways in which you can do this, beyond those purely Euro-centric technical ways. We had a panel on alternative approaches, from spiritual guardianship and work that artists are doing with communities in Hawaii and New Zealand.

Another big piece was a lot of people felt that they were very alone doing this work, that they were the only ones, and it was amazing for them to find others. There’s now a group of children of artists who are starting to talk and collaborate. I always talk about the responsibility of the ecosystem, because I feel like, as an ecosystem, we need to grapple with the realization that there are generations and generations of artists’ stories that we are losing. Artists in their 80s, especially artists of color, were often not only artists but activists and organizers, and all of that is going to be lost if we don’t do something about it now, before they pass away. It’s urgent. The narrative is key to preserve.