Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt from Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife, a new biography about Gertrude Stein from author Francesca Wade. It releases October 7 from Scribner.

The [Stein] siblings’ recollections of their early years in Paris varied considerably. Both agreed that it was Leo whose craze for Japanese prints sparked their shared interest in ‘junking’: prowling around antique shops in search of affordable art with which to adorn the atelier’s walls.

It was Leo who fell for the work of Paul Cézanne, the ageing painter he thought ‘succeeded in rendering mass with a vital intensity that is unparalleled in the whole history of painting’. And it was Leo, on the recommendation of Bernard Berenson, who first rang the bell of the tiny gallery run by Ambroise Vollard on the rue Laffitte. For Leo, making contact with Vollard (an ardent champion of contemporary artists who had mounted Cézanne’s first ever solo exhibition nine years earlier) was the natural consequence of his long-standing engagement with aesthetic theory. In Gertrude’s version of events, the visits to this ‘incredible place’ were simply a delightful form of entertainment.

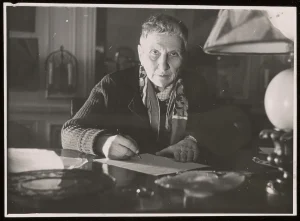

Gertrude and Leo Stein, ca. 1897.

Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Over the autumn of 1904, they were regulars at the shop, rummaging through the heaps of pictures and sending the gruff proprietor running upstairs in search of more. At this point, the Steins’ tastes were eclectic: they would buy what they could afford. Their brother Michael, still in California, continued to send them a monthly allowance from their invested inheritance, which covered their rent and living expenses comfortably—they were able to hire a housekeeper, Hélène, who cooked and managed the household budgets—and they preferred to buy art than eat lavishly or extend their wardrobes beyond their simple corduroy uniform. When Michael informed them that their stocks had outstripped all expectations and they had a surprise windfall of 8,000 francs apiece, they went straight to Vollard’s, and kick-started their collection. Their early purchases covered a range of styles: the classical Romanticism of Eugène Delacroix, the Impressionists Monet, Degas and Renoir (controversial a generation earlier, now more palatable to contemporary tastes), and more daring works by Gauguin, Van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec, who rebelled against their predecessors’ naturalistic use of form and colour. Finally, they told Vollard they had to stop—but wanted their final purchase to be something large, unusual and exciting. Vollard led them through to a back room—where Gertrude had speculated that an elderly charwoman sat churning out the canvases sold as masterpieces – and showed them a portrait of Cézanne’s wife seated in a red armchair, holding a fan on her lap, her expression enigmatic. One side of her face appeared dynamic, the other half smooth and flat as a mask. A brief deliberation over honey cakes down the street, and the painting was acquired.

But it was the following year, at the annual Salon d’Automne of October 1905, that the Steins took their first great risk, making the purchase which marked a shift in their collecting habits from modestly priced pieces by acknowledged modern masters to the cutting-edge work of marginal young artists. By this point, Michael [Gertrude and Leo’s brother] had joined them in Paris with his wife Sarah and their eight-year-old son Allan, taking an apartment just around the corner in a converted chapel at 58 rue Madame. Michael had quit his job on the San Francisco railway, finding himself on the side of the union workers rather than the management during the cable-car strike of 1902. He continued to manage the family’s financial affairs, and was inclined to be cautious where Gertrude and Leo seemed reckless: dismayed to discover his siblings spending all their money on art, he reproached Leo into auctioning off some Japanese prints. But before long he embraced the idea of a family art collection, which he had come to see as a potentially shrewd investment, as well as a source of pleasure, intellectual purpose and new social horizons.

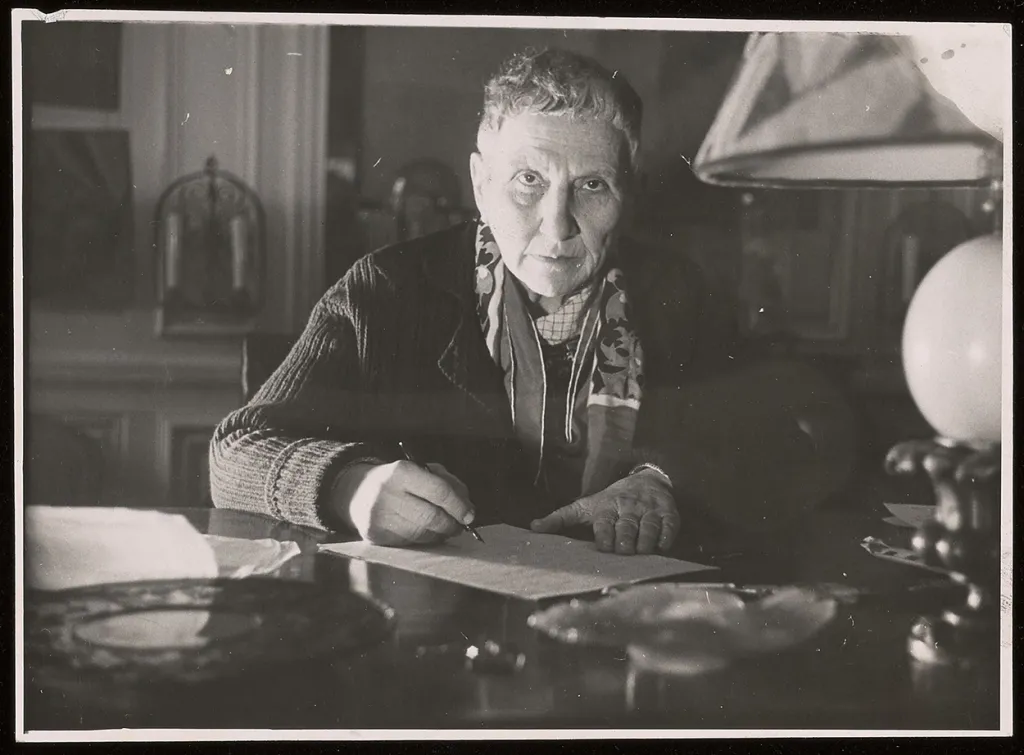

27 rue de Fleurus, ca. 1913.

Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

On the opening day of the Salon d’Automne, the Steins joined the animated throngs queueing down the Champs-Élysées to enter the Grand Palais. Once inside, they passed through several large halls and stopped at a small side room, where a commotion was brewing. On the wall hung Henri Matisse’s Femme au Chapeau, an exuberant portrait of his wife, her feathered headpiece at a jaunty angle, composed from loose daubs of paint in an explosion of blues, reds, purples and greens. Leo initially considered it ‘the nastiest smear of paint I had ever seen’—a view shared by the hordes who jeered and scratched at the painting’s surface—but after thinking it over, decided the portrait was ‘what I was unknowingly waiting for’. Gertrude claimed it was her idea to buy the painting, which she considered ‘perfectly natural’, for 500 francs. In her telling, she ‘arranged the whole matter’ with Madame Matisse herself, who urged her husband—so distraught at the painting’s terrible reception he had considered burning it for the insurance money—to command the highest price he could, since these buyers were clearly mad.

The Steins were soon seeing a lot of Matisse. Sarah joined his art class, and she and Michael rapidly became his major patrons, devoting their own collection exclusively to his latest work. But Gertrude and Leo’s attention had already moved on. A few weeks after the Salon, the dealer Clovis Sagot showed them a painting of a nude girl posed side-on against a dull blue backdrop, clutching a basket of red flowers. Placidly chewing liquorice, Sagot informed them that this unknown Spanish artist—who was so destitute he slept on a shared mattress in a run-down Montmartre studio—was ‘the real thing’. Here, unusually, Gertrude’s and Leo’s stories align. Leo immediately recognised the work of ‘a genius of very considerable magnitude’, but Gertrude was ‘repelled and shocked’ by the girl’s legs and feet, to the extent that Sagot, anxious to make his sale, offered to guillotine the canvas and jettison the lower half. They bought the (complete) painting for 150 francs. But that dynamic slowly reversed after they were introduced to Pablo Picasso by their mutual friend Henri-Pierre Roché. By the end of their first dinner together, Picasso and Gertrude were play-fighting over the last slice of bread, Gertrude concealing her giggles as Picasso, under his breath, poked fun at curmudgeonly Leo’s clichéd enthusiasm for fashionable Japanese prints. Soon, she was in and out of Picasso’s studio, discussing his work with him, lending him money, and buying his work independently. It was Leo who led the way, but Gertrude who stayed the course. Before the end of the year, Picasso asked to paint her portrait.

Excerpted from Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife by Francesca Wade. Copyright © 2025 by Francesca Wade. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.