In 1975, Susan Sontag asserted that “beauty is a form of power,” but added a serious qualification: “It is not the power to do, but the power to attract. It is a power that negates itself.” Since beauty is in the eye of the beholder, it is a “power” that can be given and taken away. And, she elaborated, one must work hard to stay beautiful—by shopping, preening, dieting, and concealing signs of aging. So beauty hardly constitutes freedom; rather, it entraps you in a loop.

Sontag’s point was buzzing in my head all autumn as I gallery-hopped around New York, which was brimming with paintings of women by women—a sort of Feminist Figuration Fall, if you will. And I wondered if her point rang differently now, when attention is currency and the surest way to earn it—to break through the algorithm—is with pictures of hot girls.

A debate about whether and how beauty is power has cropped up perennially since the dawn of feminist art. In the 1970s, artists like Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke got flak from more than one feminist critic for using their nude bodies in performances and photographs, with Judith Barry and Sandy Flitterman-Lewis writing that such work “ends up by reinforcing what it intends to subvert.”

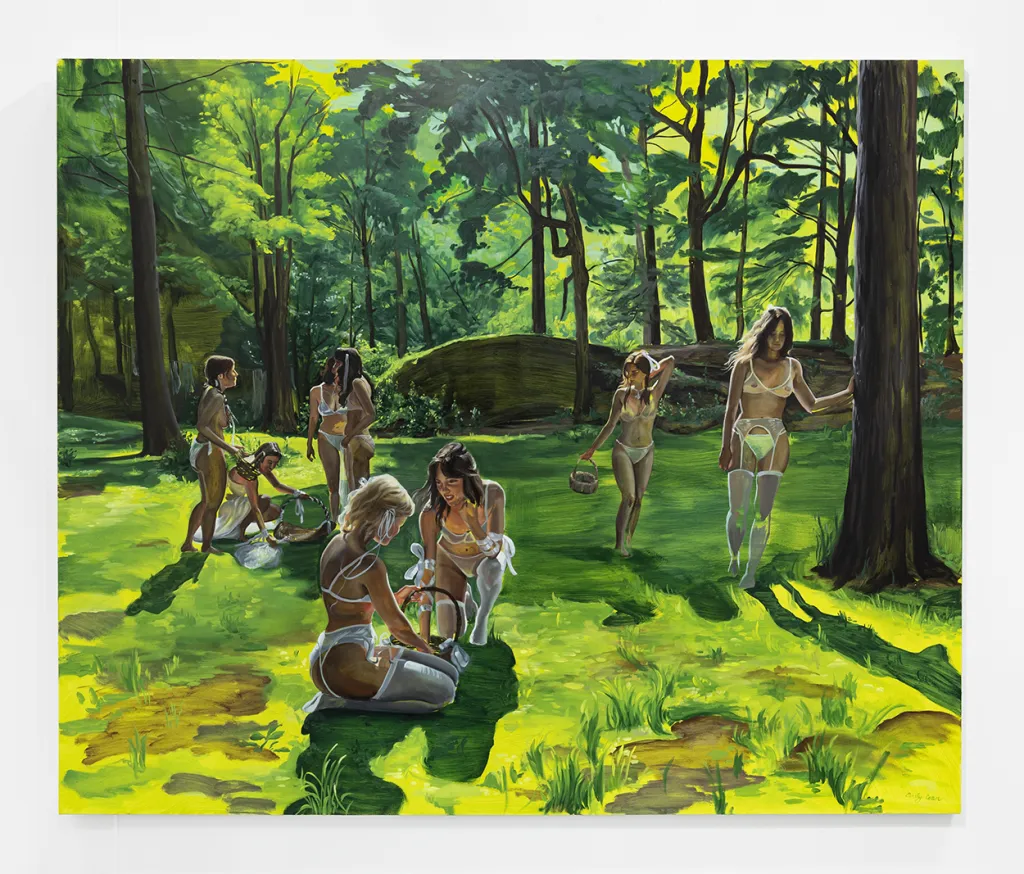

Ren Light Pan: Venus at Sunset, Dramatic Scrap, 2025.

Courtesy Lyles & King

Things got a lot better for women in the intervening half-century, and my (millennial) generation generally came to see that critique as too easy—laced with its own kind of woman-hating and the epitome of feminism’s thorny relationship with sex positivity. Today’s painters seem to largely agree that women should be able to do and paint whatever they want, and that any beautiful and/or sexualized image of women is okay—feminist, even—as long as it is by a woman and express her point of view.

But this position reduces feminism to an identity rather than an ethic or aesthetic, and it is more about the artist than the art. The fall season’s girl-on-girl paintings vary wildly, but taken together, the work proves time and again that form and content are inseparable. Consistently, the most traditional views of femininity tended to appear in the most aesthetically conservative pieces.

EMILY COAN, WHOSE WORK featured in Dimin Gallery’s booth at the Armory Show, paints loosely rendered nymph-y white women, topless and in lingerie, lounging in the woods and basking in the light of golden hour. Part of her point, she explained in Interview magazine, is to mount a reaction against any feminism that might try to shame her for enjoying such scenes. Fair enough. But the work, trafficking in normative fantasy and absent any formal innovation, is utterly pastiche in both subject and style.

The word “reclaiming” gets touted as the thing women do when they employ pictorial tropes of yore in their work. It has been applied—lazily and frequently—to the work of Anna Weyant, though for her, “regurgitating” seems more apt. Weyant paints baby-faced women in push-up bras with perfect porcelain skin, wearing outfits that I can only describe as “Upper East Side”: turtlenecks and pearls, ribbons and pleated skirts. On the podcast Going Mental, Weyant described herself as against censoring the Picassos and Gauguins of the world and cited painters like Balthus and John Currin as her greatest influences. It’s a curious squad: All four have been criticized, to varying degrees, for fetishizing youthful femininity.

None of that deters Weyant from mining their tricks. Her work drips unironically with eroticized infantilization: She’s painted doll-like girls and girl-like dolls and, this past fall, debuted an adult-size dollhouse in collaboration with fashion designer Marc Jacobs. Tellingly, Weyant was first discovered on Instagram. And most often, her work amalgamates Old Masters paintings and luxury advertisements, the only twist being the occasional strange crop, off-kilter or abrupt. Bum (2020) shows a view up a pleated schoolgirl skirt, with the woman’s head left outside the frame.

It’s easy to get attention with pictures of pretty young women—something that painters as well as art dealers, advertisers, and algorithms all know. The problem is not that these painters take pleasure in looking—that critique would be puritanical and prudish—but that the to-be-looked-at-ness of women is doing all the work in otherwise unoriginal, if skillfully rendered, canvases, and that the kind of looking they engender is one-note.

When faced with a blank canvas, where one could imagine literally anything, why double down on rehashing more of the same? It’s the very definition of conservatism. At least Nash Glynn, in works like a 2020 naked come-hither self-portrait overlooking a Van Gogh-esque vista, leans so hard into kitschy tropes that it becomes funny. But more compelling are artists making work that is consumable and challenging at the same time, with the best feminist figuration not scrutinizing beauty so much as scrambling it—until it’s funny, feral, or free.

And yet it’s hard, if not impossible, to shed the baggage of art history. A canvas, they say, is never truly blank, but always riddled with inherited imagery and conventions—which have rarely been kind to women. The same is true in art as in life: Beyond the canvas, it can be tricky to disentangle what a girl genuinely wants from what she has been brainwashed by patriarchy to desire. Art will probably never resolve all these tensions, but plenty of standout work treads honestly through the muck.

IT MAY BE TEMPTING to dismiss Weyant and Coane as low-hanging fruit—plump grapes dangled tantalizingly over the mouth of the market. But several young blue-chip market darlings are in fact imagining compelling feminist worlds through figuration.

The self-portraits in Sasha Gordon’s show at David Zwirner mesmerize and repulse simultaneously. In Husbandry Heaven (2025), her luminous skin glows eerily green and is punctuated with cellulite and stretch marks, with each of her long hairs rendered individually. Gordon stands naked save for a pair of black kitten heels, not just echoing Manet’s Olympia but talking back to it.

In It Was Still Far Away (2024), Gordon clips her toenails while noise-cancelling headphones leave her oblivious to a mushroom cloud in the distance, even as the warm glow of the nuclear bomb gently graces her face. On the next wall, in Trance (2025), she snacks on icky translucent slivers perhaps only recognizable as toenail clippings to those who’ve seen the adjacent painting. What draws you to the work is its beauty—gorgeous colors, a compelling face, glowing eyes. Then Gordon challenges all your first impressions.

Sasha Gordon: Husbandry Heaven, 2025.

Courtesy David Zwirner

Ren Light Pan’s fall show at Lyles & King similarly played with first glances. The exhibition revolved around nude self-portraits made with inky, splotchy photo transfers that walk a fine line between showing and concealing—a flirtatious opacity. I initially mistook her best piece, studio (crimson), 2025, for a big red phallus, when it actually shows a woman sitting on a stool, her slightly slumping posture giving her form a gentle curve as a urethral highlight crowns her hair. Light Pan, who is trans, stained this shape red and allowed the rest of the faint grayscale image to recede.

A stripper stars in People Loved and Unloved (2025), the standout work in Ambera Wellmann’s fall show at Hauser & Wirth. Fully nude and hanging upside down on a pole, our dancer is the painting’s largest figure and yet hardly its focal point. She is surrounded by people eating dinner: Some seem transfixed, some bored, and some dead, with Munch-esque faces mingling among spooky skulls. On the table, a chaotic array of fish and fruit offers a feast for the eyes, and in the background, I spy quite the scene—a reclining pregnant nude lies near someone who spreads their cheeks to show the viewer their anus. Nearby, a skeleton leans in to kiss a figure who looks understandably displeased.

That’s just the content; the form is equally wild, with vibrant reds paired jarringly with hazy neutrals. Decadence bleeds into decay—a strip club scene made vanitas. In Wellmann’s world, sex and beauty are just part of the strange business of having a body.

Ambera Wellmann: People Loved and Unloved, 2025.

Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

IT’S UNFAIR—AND UNINTERESTING—to read all paintings of women by women as some kind of symbol or statement about women in general. Plenty of painters, like Katja Seib and Louise Bonnet, have described to me how they paint women not necessarily to say something about women, but because they are women and simply paint what they know. Women do not have to “mean” anything; that’s an expectation worth resisting.

And yet other artists make work betraying profound ambivalence as to what feminism looks like. Sara Cwynar’s colorful, maximalist installations amalgamate tropes from product photography. Her video Baby Blue Benzo (2024), recently on view at 52 Walker, stars a model lounging on the world’s most expensive car in a pink bikini while her perfectly manicured hands caress its shiny surface. Pamela Anderson makes a memorable cameo, and in a voiceover, Cwynar expresses, by way of quotes from the Frankfurt School, ambivalence about her attraction to seductive ads—then proceeds to make an artwork that could pass for one were it not for all the words. The conflicted feelings are understandable, to be sure. I only wish the artwork expressed them visually rather than rehashing the seduction and then sprinkling in a skeptical soundtrack.

Chloe Wise: Some abysmal jam, 2025.

Courtesy Almine Rech

Chloe Wise’s fall show at Almine Rech was similarly ambivalent. It starred campy Caravaggesque paintings of skinny, pretty girls in silky outfits, glowing with slightly sickly hues that make fabrics gleam with jewel-toned iridescence and skin turn too orange or too green—a thin layer of weirdness over pictures otherwise perfect. Neither the press release nor Wise’s artist talk for the Brooklyn Rail even mentioned the subject matter—women, except for one figure—beyond a nod to the glut of fashion advertising that surrounds us, which Wise said inevitably inflects her paintings: “The images that come into my eyes come out of my hands.”

Wise’s ambivalence feels honest; most of us like pretty girls and nice things, after all, and there’s no need to overintellectualize or defend either. And yet, such ambivalence results in work that describes the world more than it reimagines it. Personally, I’m more drawn to Wise’s paintings of gagged and bound football players, sourced from photos found online, and to her grotesque shrimp and Caesar salad chandeliers. But it’s no mystery why galleries prefer the girls: Sex indeed sells.

Suspicion of beauty seems not only dishonest but also risks the misogynistic logic of framing pretty things and pretty people as shallow and vain. The beauty industry, however, deserves plenty of scrutiny, especially in an art world now merging with luxury and lifestyle industries. Seductive ads can be pleasurable, but I think they do more harm than good, designed as they are to make women feel insecure so they can sell products promising beauty.

The girlboss logic of hot girl feminism goes something like: Make pretty paintings, get money, and succeed—just don’t disrupt the status quo. But that’s a losing proposition because, to stay hot, proceeds will have to go to Botox and the latest fashion trends—as the legendary Pippa Garner once emblazoned on a T-shirt: I’D BE MORE BEAUTIFUL BUT I RAN OUT OF MONEY. Why use art to get more trapped in this loop when it could be used instead to redefine what beauty is?