There is a danger in trying to say everything and it is not that you might say nothing. It is that you might say worse than nothing: You might say something that you didn’t intend.

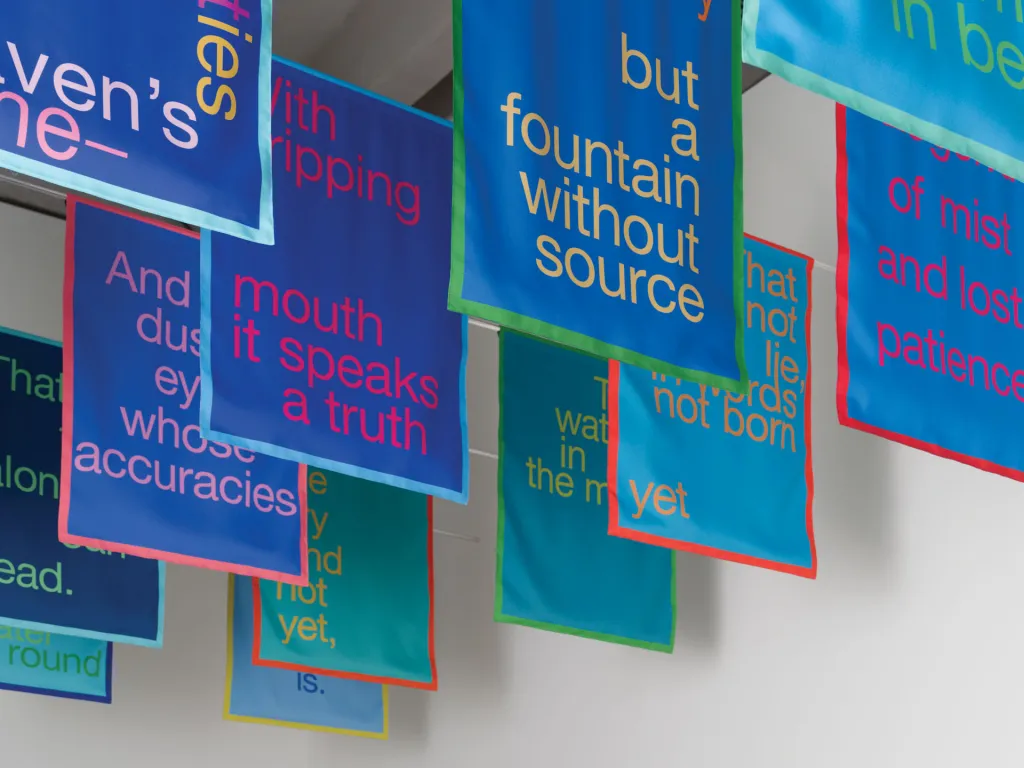

“Echo Delay Reverb: American Art, Francophile Thought,” an ambitious show at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, aims to trace the effect of 20th-century French writers on American art since the 1970s. Works from 60 artists are set alongside quotations by, photographs of, and book covers from Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Aimé Césaire, Roland Barthes, Gilles Deleuze, Frantz Fanon, Michel Foucault, Édouard Glissant, Jacques Derrida, Pierre Bourdieu, Monique Wittig, and Julia Kristeva. But while the art is generally compelling, the incoherent organization and superficial treatment of the theorists is not, and this overreach says something inadvertent and lamentable: that there is nothing that cannot be reduced to decorative script on a wall.

Imagine Guernica, rendered in sequins, on a tote bag, sold by H&M. Now do the same thing to critical thought.

Conceived by Naomi Beckwith, chief curator at the Guggenheim and two years out from overseeing the 2027 edition of Documenta, the show sprawls across the entirety of the mazy building. Its scope includes a mural by Caroline Kent; a nested Melvin Edwards retrospective; five broad thematic galleries—Dispersion, Dissemination; The Critique of Institutions; Geometries of the Non-Human; Desiring Machines; Abjection in America—and a room devoted to the journal and publisher Semiotext(e).

View of the 2025 exhibition “Echo Delay Reverb: American art, Francophone thought” at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris.

Photo Aurelien Mole

The show works best when it sticks to artists who directly grapple with theorists. There are fewer than you’d think. Paul Chan’s 2010 costume designs for a theatrical collaboration with Gregg Bordowitz, The History of Sexuality Volume One: An Opera, feature studies of a cock-dangling, chap-wearing Foucault, a cop in dom-wear, Freud, and the pope. Beautiful as standalone watercolors, the designs also signal how Foucault described institutions like the law, religion, and psychoanalysis as modern disciplinary regimes. Oriana (2024), a multichannel video by Beatriz Santiago Muñoz based on Wittig’s 1969 novel Les Guérillères, translates her linguistic experiments to cinematic form, constituting a serious reading of Wittig’s text. Andrea Fraser, an artist-practitioner whose work develops Bourdieu’s analysis of cultural capital, is represented here with her satirical performance of jargon-drenched curatorial authority in Orchard Document: May I Help You? (1991, 2005, 2006).

At other times, despite an ostensible link between theory and art, the show feels skin-deep. In the year 2025, absolutely no one needs yet another room dedicated to Kristeva’s 1980 book Powers of Horror and her account of abjection. Already by 1993, in the Whitney show “Abject Art: Repulsion and Desire in American Art,” abjection had been institutionally digested and regurgitated into cliché. In fact, what is most interesting about that history is that Kristeva was misread in that inaugural moment. Abjection described subjects intimately bound to something unassimilable, pulling us toward “the place where meaning collapses.” But Kristeva’s work was taken up in the culture-war era of “abject art” as if that unassimilable realm was a nameable list of entirely assimilable things: shit, blood, pus, piss. This unnecessary rehash does nothing to remedy that misreading, giving throwback vibes with Cindy Sherman and Mike Kelley and updating it with Tala Madani’s “Shit Moms” series (2019–). Madani’s paintings are glorious, brown pigment–spilling desecrations of an art-historical idealization of mothers and children. But they are not about abjection as Kristeva named it. Stretched past the point of recognition, there is no use for the organizing conceit of “Abjection in America” in the first place.

Other pieces are informed by theory, though it is less clear that the relevant pensées are primarily francophone. Mark Dion’s taxonomies and classifications owe more to Stephen Jay Gould (American) and Donna Haraway (American) than to French theorists. Char Jeré’s commissioned installation Zone of Nonbeing (2025)—featuring 70 black ceramic ears and a soundscape derived from satellite dishes positioned across Haiti, Chicago, Tigray, Sudan, Palestine, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Mississippi—navigates noise, witnessing, and Black life (she calls her work “Afro-Fractalist”). But it is primarily engaging a different intellectual tradition, one that could properly be called (horrors!) American critical thought. I’m talking Samuel R. Delany, bell hooks, Frank Wilderson III, Saidiya Hartman, Fred Moten. These thinkers know their French theory, but subsuming their work under that label is like claiming that because Foucault read Nietzsche and Lacan read Hegel, French theory was actually German.

Work by Char Jeré’ in the 2025 exhibition “Echo Delay Reverb: American art, Francophone thought” at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris.

Aurelien MOLE

Further selections are downright puzzling, bringing more relevant potential inclusions to mind. Baudrillard is barely present despite his enormous influence, while Sartre is overrepresented, his existentialist humanism at odds with both later French theory and the post-1970s American art scene. Likewise, Joan Jonas’s Left Side Right Side (1972) strikes a discordant note, an escapee from a show on medium ontology. One wonders why monitors aren’t instead playing Hollis Frampton’s Zorns Lemma (1970), a literal structural film that has been likened to S/Z by Roland Barthes, one of structuralism’s central figures.

The show overreaches yet is simultaneously riddled with gaps. Where are the women? I kept wondering, looking in vain for Luce Irigaray and Simone Weil, for Colette and Marguerite Duras. Sylvère Lotringer’s Semiotext(e) gets an entire room for its mix of punk culture, avant-garde experimentalism, and radical philosophy. But missing is the simultaneous founding of the journal October by Rosalind Krauss and Annette Michelson—the site where the ideas and not just the fashion of post-structuralism arrived in America.

This may seem like inside baseball stuff. But this show promised us baseball.

The day after the exhibition opened, the Palais de Tokyo removed Cameron Rowland’s Replacement (2025), a work in which the artist placed the new Martinican flag, rife with the history of anti-colonialism, in place of the French flag outside the museum. In its stead is a small wall-mounted label reading that the work was determined to possibly violate France’s principle of neutrality. A handwritten honte (“shame”) is now scrawled beneath this text. This reflexive drama stages the structure of critique without teeth: The art institution benefits from the frisson of provocation, but without accepting any risk, demonstrating that no one better absorbs the critique of institutions than institutions. (You know what critical tradition developed an astute, nuanced diagnosis of precisely that capacity? This very one on display. But you won’t get how in 20 words in a jazzy font, even if they are blazoned across a vermilion wall.)

The problem with turning theory into ornament is that when you really need it, it isn’t there.