On a spring morning in 1966, New York Times subscribers awoke to news that two bodies were found at the Guggenheim Museum. “Give a man enough rope, they say, and he’ll hang himself,” John Canaday, the paper’s art critic, wrote that April day. “The adage received double proof this week at the Guggenheim Museum.”

So what if there were no actual corpses? For Canaday, the painter Barnett Newman, who had just opened a show at the Guggenheim, was as good as dead. So too was the show’s curator, Lawrence Alloway.

In his review, Canaday torched Newman’s new paintings, a series of 14 abstractions that the artist titled “Stations of the Cross.” Canaday claimed that Newman’s show wasn’t “worth a plugged nickel” and that the museum had delegitimized itself to a point where it “can no longer be taken quite seriously.” Without any clear logical connection, he compared the black vertical bands in these paintings to “unraveled phylacteries,” referring to tefillin, or the leather boxes worn by pious Jewish men that contain verses of the Torah.

Artists get negative reviews all the time, and most simply brush them off. But Newman was one of the huffiest, prickliest painters of the 20th century—he couldn’t just ignore pushback. He’d feuded with Canaday in the past, joining a group of artists in protesting the Times critic’s open hostility toward modern art. Following the Guggenheim review, Newman opened a new line of critique.

“What do you make of his remarks that turn the ritual phylacteries into an epithet?” Newman wrote to the Times’s publisher. “Is he attacking Jesus because he was a Jew and had to wear them or is he attacking men because he knows that I am also a Jew?”

This remark was striking even for Newman, who could be vicious in situations that didn’t necessarily deserve his bile. (He was, after all, an artist who once sued his friend, the painter Ad Reinhardt, alleging that Reinhardt had slandered him when he called him an “artist-professor” in the College Art Association’s journal.) Newman’s questions regarding Canaday imply that Newman’s Jewishness was central to him as a person—so central, in fact, that anyone who denigrated his art was also denouncing his identity.

Paintings from Barnett Newman’s “Stations of the Cross” series at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Photo Bill O'Leary/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Newman’s relationship to his religion is at the core of Amy Newman’s remarkable new book, Barnett Newman: Here, which goes a long way in explaining why the painter—no relation to the author—fought so hard for himself. “It is impossible to overemphasize the impact of cultural nutrient in which Barney’s crusades were waged,” Amy Newman writes in her tome, which is thick with pages—nearly 700 of them—as well as insight. She goes on to note that, though by today’s standards the painter may appear to have an “annoyingly thin skin,” his diatribes made sense in a time when Jews had to fight to be taken seriously.

The author points out that Newman read James Waterman Wise’s 1938 “Open Letter to My Fellow-Jews,” in which Wise wrote that Western society would rather view a member of the tribe as “Mr. Zero than an Einstein.” “There was no way that Barney was going to be a Mr. Zero,” Amy Newman writes. Bingo! This is the kind of revelatory moment you want from any biography; Barnett Newman: Here contains plenty of them.

Amy Newman, an art historian whose past books include one about Artforum’s early years, isn’t the first to highlight the role that Jewish identity played in the development of postwar abstraction—others like the curator Mark Godfrey have already done so, and quite thoughtfully, too. But Barnett Newman: Here makes this artist’s religion so central that it’s hard to ignore, and that is rare. Tellingly, the book is titled after the Torah parsha read at Newman’s bar mitzvah—one of the most sacred passages of the Pentateuch, in which Moses communicates directly with God, saying: “I am here.”

It’s not as though Newman hid his Jewish identity from the public eye. He frequently led disquisitions on the Kabbalah, a form of Jewish mysticism that became, as this new biography notes, “one of the many hallmarks that he appropriated to define his historical person.” (“‘Pious,’ he wasn’t, but identified he was,” Amy Newman writes.) A 1949 painting now owned by MoMA, featuring a black stripe running through a dark void, is titled Abraham seemingly in reference to either the artist’s father or the Genesis patriarch. And one of the last events that Newman attended before his death in 1971 was an auction of antique Judaica, at which he and his wife Annalee purchased a yad, or a torah pointer.

Barnett Newman, Abraham, 1949.

Courtesy the Barnett Newman Foundation

But the association seems not to have stuck in the context of Newman’s legacy. In museums, he tends to be presented to the public as an Abstract Expressionism affiliate concerned with big questions about man’s place in the world, not as a Jewish painter with spiritual quandaries on his mind.

The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., for example, regularly shows works from the “Stations of the Cross” series—lovely canvases with sharp bands of white and black pitted against a creamy background. The texts for these works mention that these works allude to the life and death of Jesus Christ, but not that Newman was a Jew. You’d be forgiven for assuming that Newman was a Christian, just as I did at first when I encountered these paintings as a college student. When the Philadelphia Museum of Art mounted a Newman retrospective in 2002, its press release stated that the artist was born to a Russian Jewish Zionist father, but not that Newman’s religion informed his art.

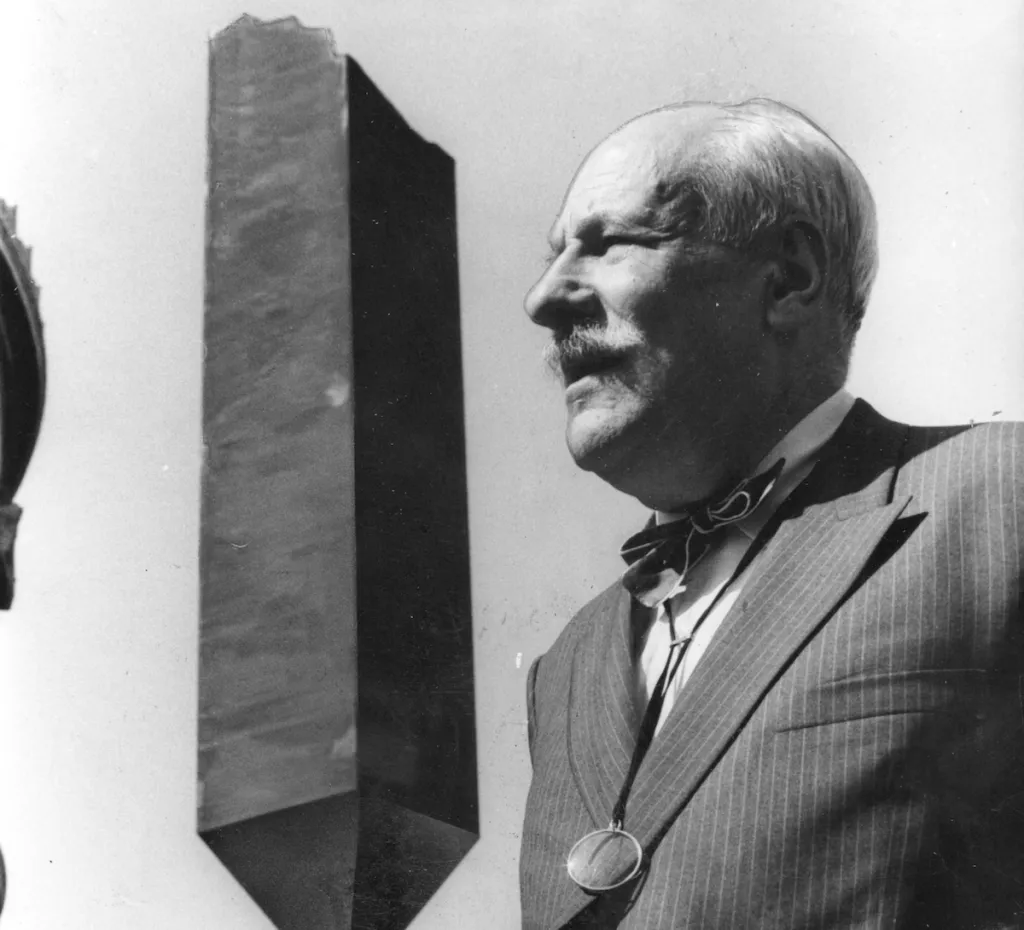

Barnett Newman, 1939.

Courtesy the Barnett Newman Foundation

Almost from the start, Barnett Newman: Here ensures that the connection between the artist and his Jewish identity is clear. Amy Newman salts her lush prose with Yiddish words—geshray, meaning “yell,” appropriately recurs throughout the book—as she spends time elucidating this artist’s vexed spirituality.

Barnett Newman grew up in relative poverty in the Bronx, where he developed an early predilection for discourse and disagreement. Just 16 pages in, Amy Newman writes that “the reflexive instinct for passion, the gamesmanship, of Jewish-style disputation would forever be one of Barney’s most marked traits.” The sensibility remained with him into his adolescence and early adult years, which included a number of failed attempts at other careers before committing to art: as a political flop with ambitions of becoming New York’s mayor, as a milquetoast critic, as a man about town. Think of all this as a cry for visibility, and then recall a remark from dealer John Kasmin quoted later in the book: “For all Jews the record is pretty important. Whatever gets written gets carved in stone.”

Newman’s art is today carved in stone, but Barnett Newman: Here usefully reminds us that it wasn’t always that way. Until the 1960s, when his spare paintings acted as a lodestar to rising artists, Newman was a laughingstock of certain critics and artist colleagues both. His canvases were vandalized on several occasions, and he failed to make into shows such as MoMA’s “15 Americans” in 1952, which helped usher the emergent Abstract Expressionist movement onto museum walls.

Barnett Newman, Vir Heroicus Sublimis, 1950–51.

Courtesy the Barnett Newman Foundation

As for his art: it takes about 200 pages for Newman to make his first great work with Onement I (1948), in which an unruly stream of orange barrels through a brownish field. Then it takes about 100 pages more for Newman to create his masterpiece, Vir Heroicus Sublimis (1950–51), in which thin lines of white and black slice down a crimson mass that’s nearly 18 feet wide.

One can easily imagine a shorter version of this book, which is periodically weighed down by run-on quotations from reviews and Barnett Newman’s dense, sometimes incoherent writings. Easy reading, it is not.

But Amy Newman is such a vibrant storyteller that she makes it worthwhile to spend so much time with a man who could be so annoying. She is not easy on him: she presents Newman as a drinker whose ire was easily stoked (“Everything provoked him,” she notes), and she often questions his self-mythologizing.

Yet she is also an inquisitive biographer determined to understand her bizarre subject. Take the thrilling section on Broken Obelisk, a 1963–67 sculpture resembling an obelisk’s snapped-off top balanced upside-down on a triangular base. The sculpture has been interpreted as a response to the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., but Amy Newman proposes that it’s actually a work about Israel, to which the artist—a “second-generation Zionist,” per this biography—pledged loyalty. Of the sculpture, she even notes that “one side—the most articulated face, the one he spent endless hours working on getting right—bears a striking resemblance to the northern boundary of Israel with Lebanon and the seized Syrian Golan Heights, as it was drawn on the maps printed in the daily papers.” I’m not sure I agree, but the point is certainly provocative.

Broken Obelisk at the Rothko Chapel. Amy Newman asserts that the sculpture can be related to Barnett Newman’s Zionism.

Photo Marie D. De Jesus/Houston Chronicle via Getty Imag

If Broken Obelisk really is related to Newman’s Jewish identity, what other of his artworks might be? Barnett Newman: Here left me wondering, in a way that has left me thinking more about his art.

It also made me curious to learn more about works I didn’t know, like Lace Curtain for Mayor Daley (1968), in which a grid of barbed wire is splashed with red blood. Mayor Daley was Chicago politician who garnered controversy by lobbing an antisemitic slur at a Jewish senator. In response, Newman said, “Well, if that’s the level he wants to fight at, I’ll fight dirty too.” As this book aptly shows, Newman had essentially already been doing just that throughout his career.