Perusing the booths of Art Basel Paris in October, I noticed there was very little digital art on view. Even works made with the tools of mechanical reproduction were shunned, it seemed—just a few photographs and screens here and there. No algorithms. No large language hallucinations. No motion-sensing interactions.

Instead, the majestic halls of the Grand Palais were filled with art made by hand. I saw splattered paint, knotted rope, braided yarn, chiselled wood and filigreed metal. The objects flaunted their virtuosity. They were proudly, defiantly analogue.

Was this art as a last stand for humanity? In this year of feverish anxiety about artificial intelligence (AI), the art world seemed to be staging a rally for art created by flesh-and-blood people.

I was intrigued but not surprised. What I saw that day at the Grand Palais resonated with several threads in my new book, The Future of the Art World, a collection of dialogues with artists, curators, academics, patrons and art-business leaders. While reluctant to specifically predict the future in it (that would be a fool’s errand), I do lay out some plausible forward scenarios in my introduction to the conversations.

‘An analogue sanctuary’

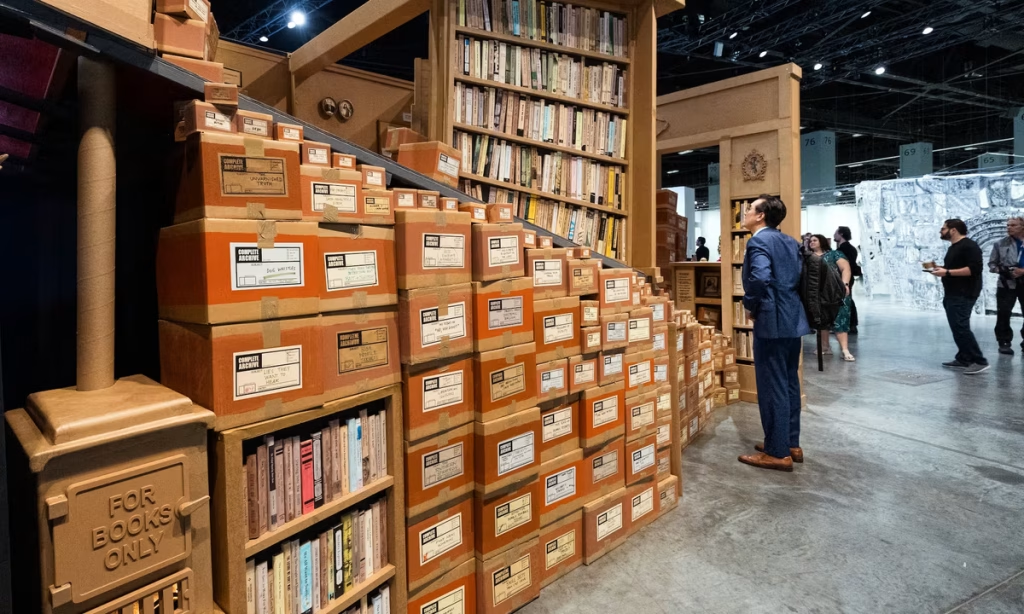

One of them is a kind of strategic retreat—or advance, depending on your view—whereby the art world, and especially museums, might transform into what I called an analogue sanctuary.

In this version of the future, the legacy art world would double down on what it has long done well. It would showcase rare and unique objects made by humans for humans.

The institutions of art, instead of co-opting new digital genres—building on what they have done, albeit at a glacial pace, with photography and video—might let digital spectacles splinter off into their own sub-industry, as theatre did vis-à-vis cinema nearly a century ago. Immersive and AI art, with their seemingly limitless thirst for large spaces, new skill sets and energy-guzzling technology, would carve out a parallel lane for digital productions.

The analogy for an analogue-first strategy comes from the watchmaking industry. Confronted by the spectre of its demise in the 1980s, when battery-powered watches flooded the zone, haute horlogerie scaled even higher. It circled the wagons around savoir-faire, inventing timepieces of mind-boggling complexity (and price) that celebrated classic materials and mastery. All in all, the strategy paid off, at least for the manufactures that survived.

I am not predicting that this is where the whole art world is headed. Next year’s global art fairs, for all we know, may be chock-a-block with human-machine collaborations. But the art world, at its best, functions as a bellwether, a keeper of the zeitgeist. And right now, as our culture, economy and politics disappear into digital screens, it seems to be sending a message. It is not unreasonable for art institutions and markets to support creativity that algorithms cannot touch.

I spoke with some of the leading protagonists of digital and AI-enabled art for my book, including Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst, Refik Anadol, Agnieszka Kurant, Michael Connor and Simon Denny. While clear-eyed about the downsides of AI, they rejected the view that machines are about to displace artists.

As Herndon put it: “AI models can simulate a kind of creativity that can produce new things, for sure. But the idea of that threatening human creativity is silly.” What I found, somewhat to my surprise, is that many trailblazing artists of the digital age are deeply committed to and protective of the art world’s institutional scaffolding.

To be clear: I am not advocating here for an escape into the analogue sanctuary. Quite the contrary. I believe that museums and galleries should engage with the best of these nascent forms of art-making, and that it is instructive to listen to those who are fluent in new creative languages. But we may find that, for the time being, the art world thrills to unique objects made by human hands.

- András Szántó, a strategy adviser to museums, foundations and commercial brands active in the arts, is the author, most recently, of The Future of the Art World: 38 Dialogues (Hatje Cantz)