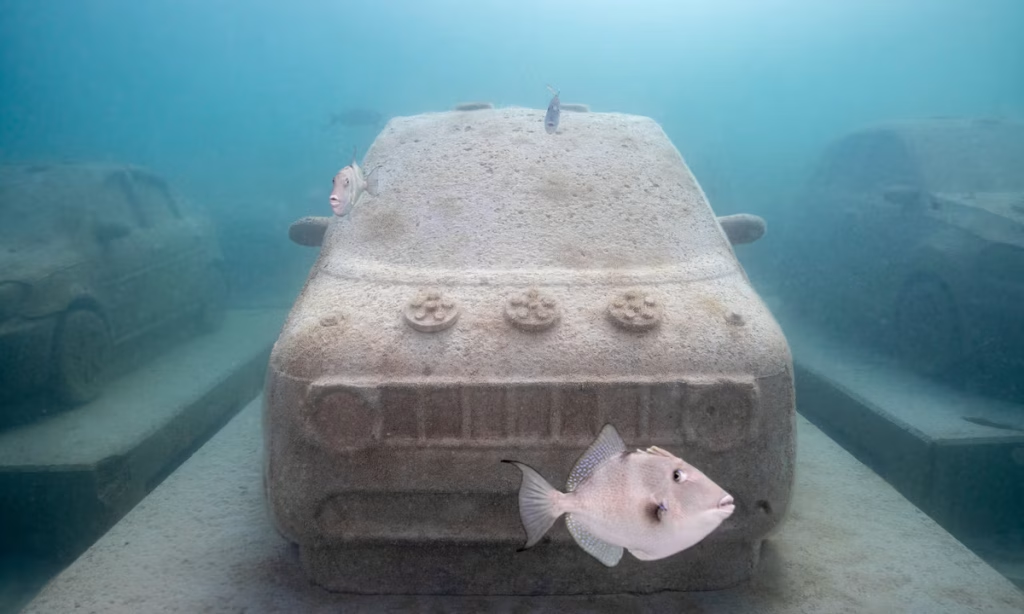

A large installation by the Argentine artist Leandro Erlich, consisting of 22 submerged marine-grade concrete cars on the ocean floor that seem to drift towards nowhere as the current flows through them, marks the first phase of the Reefline project just off the shores of Miami Beach. This underwater sculpture park, located 21ft below the waves and 600ft from the beach, is designed to resemble a hybrid reef that will support coral regeneration and marine biodiversity. Over the next ten years, new art installations will be added until it reaches seven miles in length. The project, intended to demonstrate how art and science can drive real solutions to climate change, was developed by the cultural producer Ximena Caminos and features a masterplan by the architect Shohei Shigematsu of the firm OMA.

The image of an underwater traffic jam is likely to resonate with locals and visitors alike, who are known to bond over their frustrations with South Florida’s gridlock. Erlich’s sculptures were fabricated using 3D-printing technology and are designed to become covered by live corals. Renowned worldwide for sculptures and installations that disorient viewers with trompe l’oeil effects and optical illusions, the artist found an unexpected vanishing point while working on Concrete Coral (2025).

“Underwater, this traffic jam colonised by nature looks like a submerged civilisation from the past. It has something of the myth of Atlantis in it,” Erlich tells The Art Newspaper. “This work transforms a vehicle of negative impact into something that now serves nature.”

Visitors can reach the installation by swimming, diving, snorkelling, kayaking or using electric paddleboards designed by BMW and SipaBoards. The initiative—developed by the BlueLab Preservation Society in partnership with the city of Miami Beach and a large team of biologists, engineers and artists—is intended as both a unique public art attraction and long-term ecological infrastructure: it will expand over decades as organisms grow over the structures and consolidate a resilient underwater landscape.

During Miami Art Week (1-7 December), a floating marine learning centre is anchored at the site, where scientists and artists welcome the public to explore the challenges of coral restoration and encourage them to plant their own coral. Reefline is not the only project urging visitors this week to think about marine ecology: at the nearby fair Untitled Art, the curator Allison Glenn has organised a special-projects section around the theme of water as both a metaphor and an art-making material.

Parking art underwater

It took a 157ft-long construction barge, heavy-lift cranes and impeccable logistics to submerge Erlich’s 22 cars off the coast of Miami Beach, between 4th and 5th Streets, in late October. Within minutes of being installed, fish began swimming curiously around the cars’ hollow shells.

“The Reefline project is very specific to Miami,” Erlich says. “You can have museums, galleries or fairs in any city in the world, but not all of them have a sea where you can plant corals.”

The new work reimagines Order of Importance, the installation that Erlich presented during Miami Art Week in 2019, which consisted of 66 life-size sculptures of cars and trucks covered in sand, arranged in an unsettling traffic jam on the beach. That piece sparked an idea in Caminos that it was not enough to create works that raise environmental awareness.

The artist Leandro Erlich (left) with the Reefline founder Ximena Caminos during one of the deployments to send sculptures to the sea floor Photo: Veronica Ruiz

“When we had to dismantle that installation, it broke my heart, and the $400,000 we spent went down the drain,” recalls Caminos, Reefline’s founder and artistic director. “I said to myself: how can I create something with that impact that isn’t disposable?”

In this way, Reefline offers an unusual approach to public art: the pieces in this park are subject to the will of the ocean and designed to transform over time. “What makes this project unique is the intersection of worlds: art, science, biodiversity, entertainment and community,” Caminos says. “This corridor will continue to grow for years. Its true form will be written by the ocean.”

The project—and Erlich’s conjuring of a submerged traffic jam—is particularly apt in a region that is acutely at risk from global warming and sea-level rise. Coastal flooding in Miami Beach specifically and South Florida in general is already a chronic and enormously costly problem that is only going to get worse.

Inside the coral studio

An ocean heatwave in 2023 has decimated a huge share of Florida’s coral reefs; two important species, elkhorn and staghorn coral, were declared functionally extinct in the state’s waters in research published in the journal Science in October. This bleak situation has made the work being done a few miles inland from the Reefline site especially crucial.

In an industrial warehouse in Miami’s Allapattah neighbourhood, blue lights illuminate rows of water tanks—huge coral aquariums—that pulsate alongside air pumps and high-precision filters. LED lights re-create the blue spectrum that passes through the layers of the ocean, while small polyps open and close to trap plankton inside tanks containing hundreds of gallons of water. The Reefline coral lab is where the marine biologist and artist Colin Foord, the co-founder of Coral Morphologic, cultivates the octocoral species that will later be grafted onto the sculptures.

A concrete car is lowered into the water off South Beach as part of Erlich’s sculpture project, the first piece in the Reefline sculpture park Photo: Nico Munley

“Each car will get 100 corals. It’s 22 cars, so we’re talking about 2,200 corals in total,” Foord tells The Art Newspaper. The oldest fragments in the lab are around eight months old; the youngest, nearly two. An individual coral can grow four to eight inches in a year. Foord adds: “Unlike a conventional work of art, here the art begins when you submerge it. Nature completes the piece.”

The species of soft coral being grown in the lab, which are very common in Florida reefs, “grow like bushes, branch out, filtering the water, absorbing the energy of the waves, and creating habitat. They are visually striking and much better for fish refuge,” he says. The corals will need between three and five years to fully “bloom” on the car bodies.

More art going under

The next deployments, starting in 2026, will include Heart of Okeanos by the London-based artist Petroc Sesti, a monumental sculpture based on the heart of a blue whale that represents a symbolic offering to the Greek Titan god of the oceans. Also in the pipeline is The Miami Reef Star by the Puerto Rico-born, Miami-based artist Carlos Betancourt and the Miami Beach-based architect Alberto Latorre. It will consist of 46 star-shaped modules that, once installed, will have a diameter of nearly 90ft and be visible from planes flying over the area. OMA, the architecture firm co-founded by Rem Koolhaas that is behind Reefline’s masterplan, is also designing geometric modular units that stack to adapt to the topography of the seabed and function

as breakwaters.

In addition to its artistic and scientific features, Reefline has a civic and political dimension: in 2022, residents of Miami Beach voted to provide $5m in financing for the project through the city’s arts and culture general obligation bond. The project has also received support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Blavatnik Family Foundation, the singer Gloria Estefan and her husband Emilio, Michele and Don Soffer, Karla and Dylan Dascal and others in the Star Founding Members programme.

So far, according to Caminos, Reefline has raised around $6m in all, which will allow the first phases to move forward. Her goal is to reach $30m. She hopes Reefline will provide a model that can be replicated in coastal cities around the world, and that empowers future generations to drive collective action. She adds: “If we continue to behave this way, we are going to crash.”

- Reefline, at 4th Street, Miami Beach