In the decades before the First World War, Munich was celebrated for its so-called “painter princes”—a tiny group of top-tier artists who set themselves up in grand mansions, turning out wildly popular salon paintings, mythological scenes and portraits of other A-listers. The last of these great artist-aristocrats was Franz von Stuck, one of Europe’s most important Symbolist painters, who was also a sculptor, an architect and a designer. His Gesamtkunstwerk was his own home, the Villa Stuck, an extravagant, if eccentric, showplace, built in two stages between 1897 and 1915. On 18 October, the museum reopens after a €13.5m renovation.

Damaged in the Second World War, then donated to the city of Munich, before being turned into a museum in the early 1990s, the Museum Villa Stuck has a dual purpose: to present Stuck’s manifold talents and to mount special exhibitions, including work by cutting-edge contemporary artists. Both aspects of the remit have been rethought as part of the year-and-a-half-long redevelopment.

A main goal of the project was to update and upgrade the building’s infrastructure, including its security system, and this has coincided with the restoration of the facade and a renewal of the museum’s historical rooms. The adjoining music and reception salons boast, as they did before, sumptuous decorative features, including elaborate flooring and Pompeii-inspired wall paintings by Stuck. But thanks to the conservation of art and objects, and the dramatic inclusion of new silk curtains that serve as a room divider, the overall effect is much brighter and more dramatic.

An installation view of Villa Stuck’s rehang, showing Franz von Stuck’s The Guardian of Paradise (1889)

Photo: Jann Averwerser

The new vermillion-red colour of these curtains plays off several other elements in the salons, including the restored Italian Baroque painting hanging nearby, says Margot Th. Brandlhuber, the museum’s head of collections.

The museum’s display of Stuck’s paintings has also been reconfigured, with fresh exhibits including a recently donated work, Portrait of a Woman from Mainz (1914). It still has its original artist-designed frame, whose swirling relief seems to suggest loose brushstrokes. In addition, the museum has taken the opportunity to increase the total number of Stuck paintings on view.

Stuck, who came from humble Bavarian origins—the noble “von” added when he was in his 40s—first made his name as a graphic artist. When he was still in his 20s, he began earning large sums for mythological and religious paintings that German art publishers were able to reproduce and sell in various formats, including black-and-white prints. The artist “had a strong instinct for marketing”, says Brandlhuber.

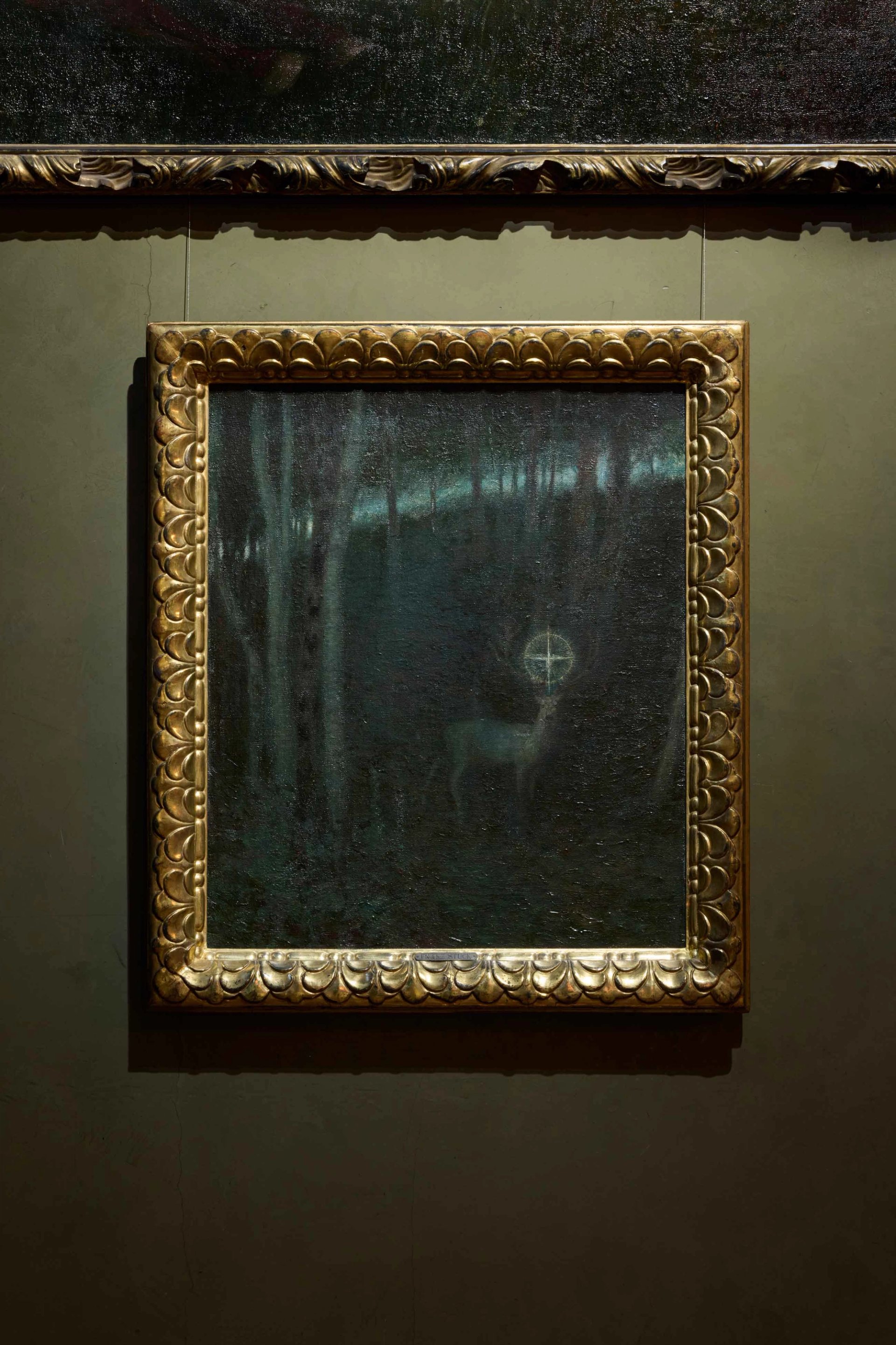

An installation view of Franz von Stuck’s The Vision of Saint Hubertus (1890)

Photo: Jann Averwerser

Stuck is now best-remembered for co-founding, in 1892, the Munich Secession‚ an association that helped usher in a generation of avant-garde art throughout Central Europe—and for the painting The Sin, a masterpiece of the Symbolist movement, depicting a swooning Eve and a demonic Serpent enveloping her. The motif dates to the early 1890s but came to exist in several versions. The Villa Stuck’s piece, created before 1906, is enshrined in a marble altar, designed by the artist—which has been conserved as part of the restoration. A collection of sculptures from antiquity and by Stuck surround the painting.

The villa will reopen with a contemporary art exhibition: A Song of Ascents is the first museum show dedicated to the work of the young Manchester-based artist Louise Giovanelli. The exhibition, first held earlier this year at the UK’s Hepworth Wakefield, makes use of the villa’s refurbished historic spaces, including the room housing the Sin altar.