The first people to migrate to North America may have sailed from north-east Asia around 20,000 years ago. Experts have argued that prehistoric people in Hokkaido, Japan, used similar stone tools to those later found in North America, and suggest that seafarers may have travelled to the continent during the last ice age, bringing this stone technology with them. This adds weight to the theory that the first Americans arrived much earlier than previously thought.

“We can now explain not only that the first Americans came from north-east Asia, but also how they travelled, what they carried and what ideas they brought with them,” Loren Davis, a professor of anthropology at Oregon State University, said in a statement. “It’s a powerful reminder that migration, innovation and cultural sharing have always been part of what it means to be human.”

Archaeologists have long debated when the first humans arrived in North America. Previously, the main theory was that people travelled by foot, around 13,500 years ago, crossing a now-submerged land bridge from eastern Russia, and then moving south along an ice-free corridor between the massive ice sheets that covered Alaska and Canada.

But in recent decades, experts have uncovered increasing evidence for earlier migration. The most dramatic finds come from White Sands, New Mexico, where 61 human footprints preserved on the edge of a dried-up prehistoric lake have been dated to between 16,000 and 20,000 years ago. Not all scholars agree with this dating, however, and some remain unconvinced by the other evidence for earlier migration.

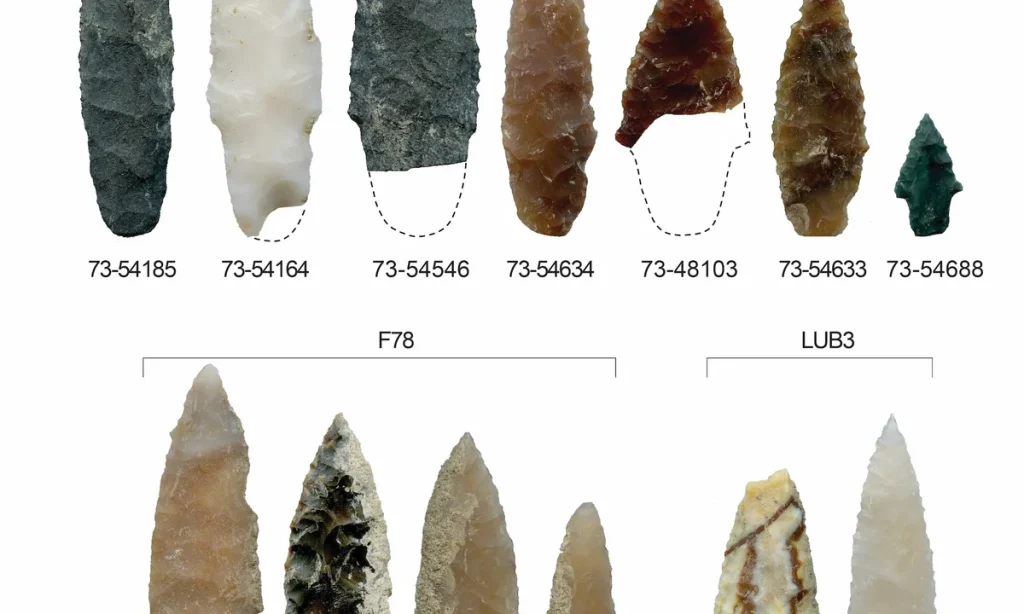

To look deeper into this problem, Davis and his colleagues studied stone tools—mainly sharp projectile points used for hunting—excavated at prehistoric sites across the United States, primarily in Virginia, Pennsylvania, Texas and Idaho. After studying the tools’ production methods and appearance—factors that can help experts differentiate between cultural groups and time periods—the team searched for similar examples from outside the Americas.

Excavator at work recording artifacts at Cooper’s Ferry, Idaho Courtesy Oregon State University, via Flickr

Their research, along with genetic evidence indicating an Asian origin for the earliest Americans’ ancestors, led them to investigate artefacts from Hokkaido, the northernmost island of Japan. From excavated prehistoric sites on the island, they identified stone tools dated to around 20,000 years ago that represent an early form of the projectile points later found in North America, both in certain aspects of their design and their production techniques.

“This marks a paradigm shift. For the first time, we can say the first Americans belonged to a broader Palaeolithic world—one that connects North America to north-east Asia,” Davis says.

None if by land, who if by sea?

Reconstructing how these early people travelled to North America remains difficult. One option is that they migrated rapidly by sea.

“By [around 30,000 years ago], Upper Palaeolithic seafarers were using sea-going vessels to access some of the outer islands in the Japanese archipelago … and were capable of negotiating the Kuroshio Current, one of the fastest in the world,” Davis and his colleagues write in their paper, published in October in the journal Science Advances. “This suggests that such experienced seafarers may also have been capable of handling adverse Pacific coastal currents.”

Nonetheless, the team also suggest that the journey could have happened at a much slower pace. In this reconstruction, the prehistoric seafarers gradually followed a route along the Pacific coast.

“This migration may have taken place over the course of a thousand years or more, lasting 40 to 50 generations and involving a series of movements of people from one place to another relatively nearby location,” the authors write. “This wave of advance population movement may easily have used short coastal voyages in waters between off-shore currents and the wave breaker zone and could have enabled such migrants to access coastal refugia, which became differentially available through time.”

More evidence for these early voyages may lie underwater in the eastern Pacific rim, submerged when sea levels rose at the end of the last ice age. Only further archaeological excavation and research, across both North America and north-east Asia, will help to solve the mystery of America’s first arrivals.

“This study puts the first Americans back into the global story of the Palaeolithic—not as outliers—but as participants in a shared technological legacy,” Davis says.