Gerhard Richter turned 93 this year, and has still been hard at work. Though he officially gave up painting in 2017, with a final sequence of elaborate abstracts, he has recently been turning out small, exquisite, painterly works on paper. And now the full range of his very long career, from his breakthrough photographic paintings of the 1960s to last year’s ink-cloud drawings, will get what can only be called a gargantuan showcase this month, when the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris mounts Gerhard Richter, a 275-work retrospective.

The show is curated by two perennial Richter watchers: Dieter Schwarz, the former longtime director of Switzerland’s Kunstmuseum Winterthur, and Nicholas Serota, the former longtime director of Tate. The two were suggested by Richter himself, when the Fondation Louis Vuitton approached the artist about doing an exhibition.

The goal from the beginning, Schwarz says, was “to do a really comprehensive show” whose only constraint was the foundation’s over 3,000 sq. m of Frank Gehry-designed gallery space. The curators were met with open doors from both public and private collections. “The fact that Richter is still alive meant that nobody wanted to say no,” Schwarz says.

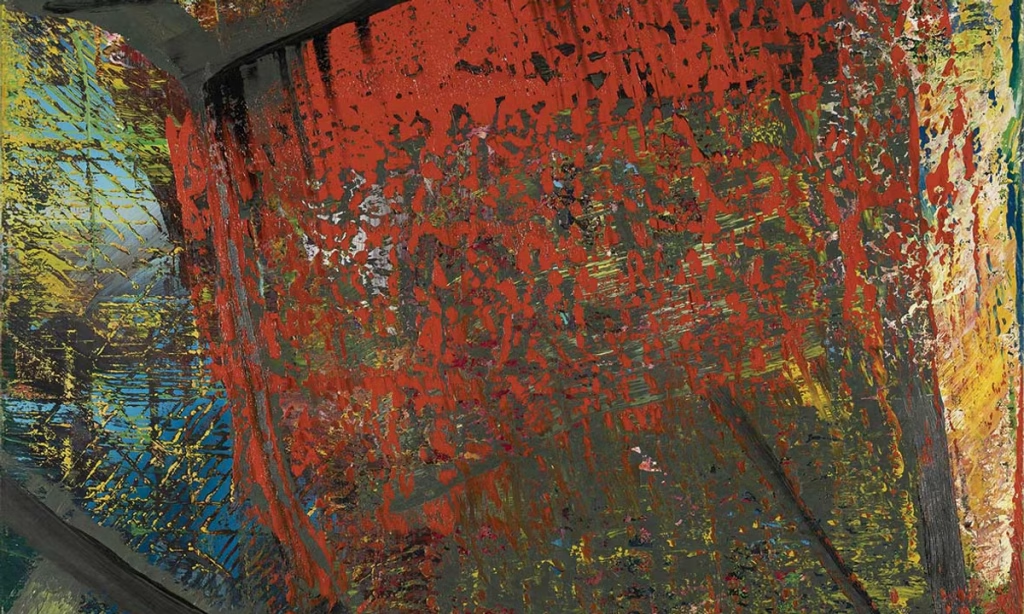

Richter has had a career marked by radical reinvention. His early photographic paintings—such as Uncle Rudi (1965), a blurred interpretation of a family snapshot, showing a smiling relative in Nazi-era military garb—now seem a world away from the brash 1980s abstract works made with the help of a squeegee. And these works, in turn, seem almost unrelated to the crystalline strip paintings of the early 2010s.

Richter’s Uncle Rudi (1965), which depicts the artist’s relative in a Nazi-era uniform

© Gerhard Richter 2025

In order to deal with the variety of the work, and the sheer number of pieces, the curators have opted for a “strictly chronological” approach, Schwarz says. The show will open with the painting that Richter now regards as his very first, the grey-on-grey Table (1962)—a blotted-out, bare-bones image that hints at the artist’s even earlier work, inspired by the French painter Jean Fautrier. Spread out over 34 rooms, Gerhard Richter will wind down with a display of very recent drawingsthe size of standard A4 paper, in which Richter relies on a solvent to dilute ink, leading to unpredictable, fanciful shapes, rendered in severe colours and named after the dates they were made.

A deference to chance, it turns out, is a unifying element in Richter’s career, say both Schwarz and Serota. While the signature blurriness of his early photo paintings was deliberate, perhaps it anticipates the dribbles and deviations of paint that would mark later decades of abstract canvases.

The other great through line in his career is a keen awareness of German history. Uncle Rudi is remembered as one of West Germany’s first major works to address Nazi Germany’s wartime culpability, and the Dresden-born Richter—who fled East Germany a matter of months before the wall went up in 1961—would go on to make complicating allusions to notable Germans as diverse as Johann Sebastian Bach and the Baader-Meinhof Gang terrorist Gudrun Ensslin, commemorated in the 1987 abstract painting, Gudrun.

Richter versus Kiefer

In the art world fame sweepstakes, the taciturn Cologne-based Richter vies for top billing with his garrulous fellow German, the France-based Anselm Kiefer. The two explore the implications of Germany’s past, but the similarity ends there. Serota sets apart the “complexity” of Richter’s historical allusions and considerations from the “rhetorical” images of Kiefer, whose use of found objects like barbed wire give his immense works a literalness quite distinct from the more equivocal, even hermetic quality of Richter’s paintings.

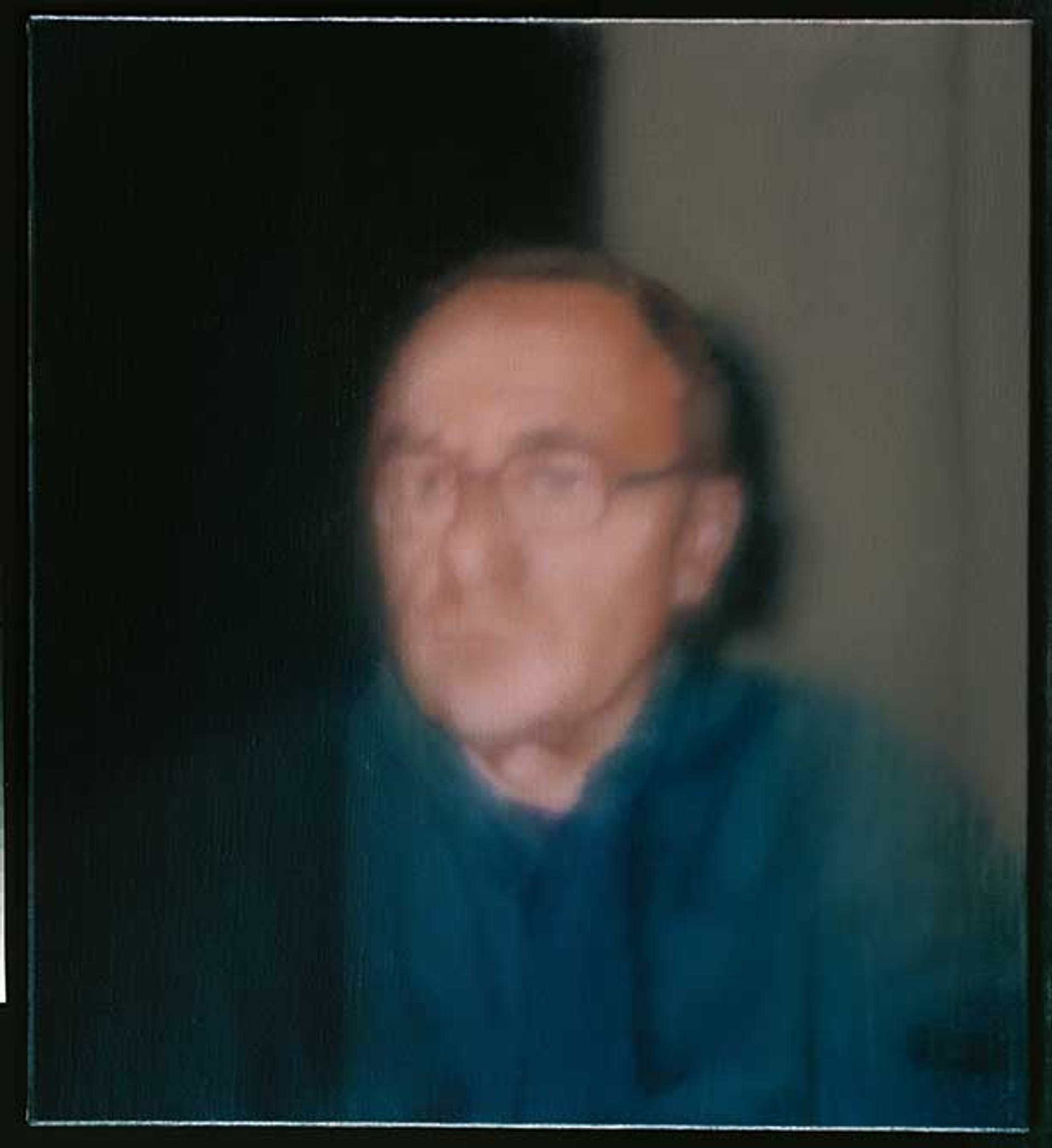

Richter’s Self-portrait (1996), which perhaps sums up Nicholas Serota’s view that Richter is “never really satisfied”

© Gerhard Richter 2025

Kiefer’s face, voice and amiable demeanour are fixtures in the art world; Richter, who rarely gives interviews and has all but stopped going to openings, is much more remote. The Paris survey includes a rare self-portrait from 1996, showing Richter’s blurred head encased in soft, abstract colour blocks. The expression, insofar as we can make it out, is unsettled. Serota, who first became aware of Richter in the early 1970s, says putting the show together has revealed to him a goading but dynamic aspect to the artist’s life and work, one this self-portrait might seem to sum up: “He’s never really satisfied.”

• Gerhard Richter, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, 17 October-2 March 2026