A few years ago, at Art Basel Paris, London’s The Gallery of Everything wanted to show the work of the late self-taught Haitian painter Hector Hyppolite, who is today considered a pioneering artist associated with the Surrealist movement. The response from the fair, gallery founder James Brett told ARTnews, was essentially: “Not now.”

With Hyppolite having now appeared in several Surrealism blockbusters mounted last year to mark the movement’s centennial, the gallery is finally bringing his work to Art Basel Paris, which opens to the public on October 24. Billed as the artist’s first survey in Europe, the solo booth in the fair’s Premise sector will feature works by Hyppolite, including three previously featured in “Le Surréalisme en 1947,” a historic exhibition that appeared in Paris that year.

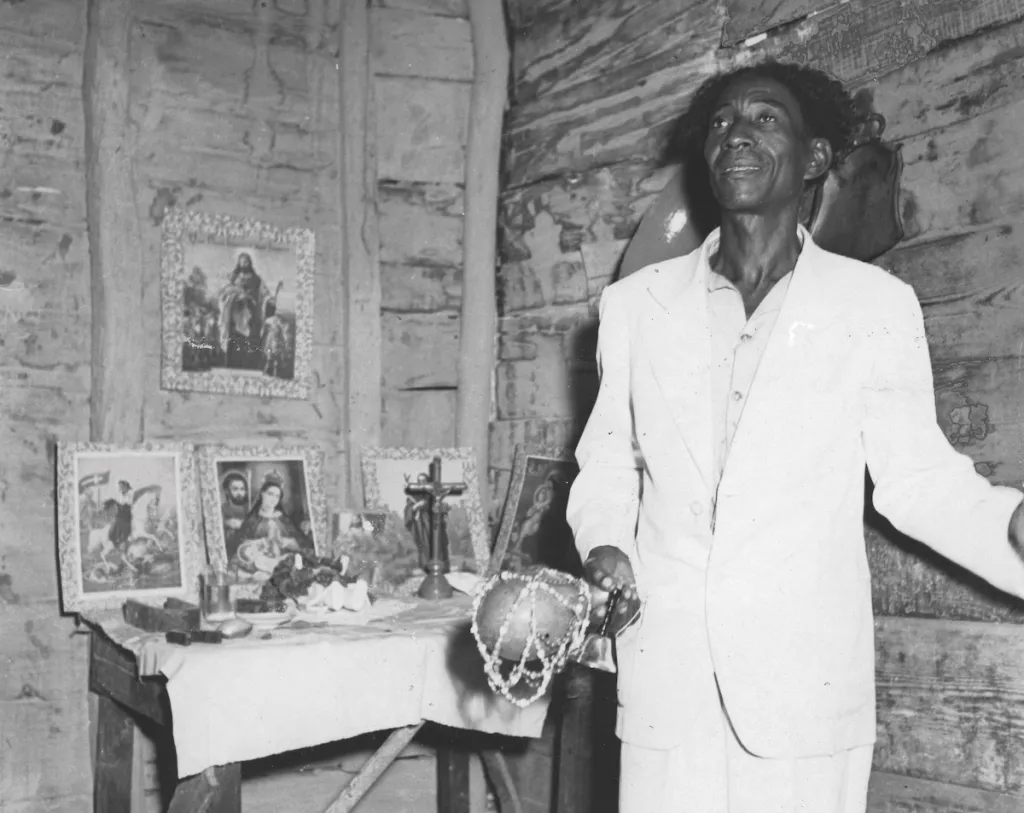

On display will also be documentation, photos of the artist from 1946, and an essay titled “Haiti on my mind” written by Malian filmmaker and writer Manthia Diawara, who worked with Terri Geis, an art historian, curator, and museum educator.

“This show is superior and better contextualized than anything else that’s ever been presented. It’s a unique opportunity to see his work,” Brett said, recalling that his good friend introduced him to the “pretty spectacular paintings” of Hippolyte some 25 years ago. The works, he said, “were so unusual, dynamic and beautifully painted, and his story was so unique.”

Hippolyte was born in 1894 in Saint-Marc in Western Haiti into a family of vodou priests. He made shoes and painted houses before becoming the artist perhaps best known for his colorful depictions of vodou gods and spirituality in the Caribbean nation in his work as an artist. He is said to have produced hundreds of paintings before his untimely death at the age of 54 in 1948, just as his star was rising internationally.

His fame abroad was thanks in part to the efforts of French writer, poet, and the founder of Surrealism, André Breton, who traveled to Haiti in 1945 for an exhibition by the Cuban painter Wifredo Lam. While there, Breton gave lectures to university students and witnessed vodou traditions on the island. Breton also visited Le Centre d’Art d’Haïti, founded by American artist Dewitt Peters, through an introduction by the poet Philippe Thoby-Marcelin; Breton came into contact with, and was mesmerized by, the work of several self-taught artists, including Hyppolite, a vodou priest who painted with chicken feathers, brushes, and his fingers. (Hyppolite relocated to Port-au-Prince, the Haitian capital and worked in a studio space provided by Peters.)

Hector Hyppolite, Untitled (Figure), 1945.

Courtesy the Gallery of Everything

Before returning to France, Breton and Lam acquired artworks by Hyppolite, some of which were featured in “Le Surréalisme en 1947,” which he organized with Marcel Duchamp at Galerie Maeght in Paris in 1947. Hyppolite’s Papa Lauco (1947) is on the second page of the catalogue of the exhibition, which otherwise mostly featured famous white American and European Surrealists. Brett said the exhibition offered “a new way to look at Surrealism, a new way to look at art.” Hyppolite, Brett added, was “really the first Black Surrealist in a real way—certainly, the first Afro-Caribbean Surrealist.”

Works by artists such as Hyppolite were often featured labelled “naïve” or “primitive.” These labels, Brett said, are “intended to say ‘OK, well, here is the high, and here is the low.’” Hyppolite’s work may have fallen for some at the time in the latter category, but with the canon expanding and museums broadening what they collect, the reception of Hyppolite’s work is changing.

“I think that that gap is getting smaller now,” Brett said. “Every year, it gets a bit smaller. And my interest is to try and be an advocate for the ‘low.’ Because I find the ‘low’ is not really low. It’s just at the side.”