Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt from Mavericks of Style: The Seventies in Color, by Uri McMillan. It releases October 21 from Duke University Press.

[Grace] Jones and [Ming] Smith initially bonded over the obvious—neither fit into the modeling world’s narrow ethos at the time. Jones very briefly worked for the Black Beauty agency but left after a month because she was told her facial features did not fit within “Black beauty” standards: “They said, Your face doesn’t fit. You are really black and your lips are big but your nose is too thin and your eyes are slanty. You won’t get the catalog work that brings in the big bucks.”1 Both were also initially passed over by Wilhelmina Models, opened in 1967 by Dutch-born model Wilhemina Cooper, presumably because neither was potentially marketable in Cooper’s eyes. But perhaps even more fundamental, they both felt an urgent desire for aesthetic freedom. “It was a much more conservative time,” Smith said. “We didn’t fit in as regular models. We were too exotic, too light, too dark.” Jones concurs, remarking that she was perceived as “too black for the white world, not black enough for the black world.”2 Smith adds that Jones was often perceived as “too much,” code for either her unconventional, exotic look or her gregarious personality. They shared a lot of the same friends in the industry and, as struggling models, were both attempting “to find our way, to express ourselves.” Smith used modeling to pay for her photography, while Jones considered trying her luck as a singer. In addition, they had similar liberal viewpoints, especially regarding sexual orientation: “We didn’t judge. We were open to the times. We were not trying to put people in a box.” But ultimately, when contemplating their friendship, Smith recalls being drawn to something more ephemeral: “I love her spirit, then and now.”3

Grace Jones at Cinandre, New York, 1974

Ming Smith

Smith attempted to capture this elusive essence when she photographed Jones at Cinandre in 1974. Wearing a two-tone tutu and holding ballet shoes in her hands, Jones faces the camera head-on with a demure look. Her hair is in a closely cut, short Afro, her hairline shaved high above her forehead. Jones’s profile is reflected in a long mirror on her left, above a row of outlets and under illuminated lights, which cast a warm glow on the left side of her face. The profile of an unidentified man in a light T-shirt and dark pants is also reflected in the mirror. His ink-colored arms and head are almost indistinguishable from the wall he is walking past. Smith recalls that Jones came to the salon wearing the outfit she was photographed in, presumably from a previous modeling shoot, and that the photograph was not planned but rather happenstance. She remarked on this destiny elsewhere: “When I photographed Grace Jones at the hairdresser, I was there to get my hair done too.”4 Smith’s resulting photograph, Grace Jones at Cinandre, is somewhat surprising in its straightforward rendering of Jones, who appears overtly feminine in her attire and almost muted in her facial expressivity. The black-and-white image portrays a rarely seen side of Jones, particularly in the 1970s: quiet, even a bit withdrawn, minus the overt embellishment or palpable confidence we see later in the decade. This is, perhaps, because “Grace Jones wasn’t Grace Jones,” Smith emphasized—not yet a star, but rather a relatively unknown model trying to break through.5

Smith’s choice of black-and-white film may seem at odds with Jones’s colorful personality, yet it was consistent with the artistic hierarchy of the era, as we have seen. “Black and white was the preferred art form,” Smith told me, a sentiment shared by the other members of the Kamoinge Workshop. Black-and-white film and its “great gradation scale,” she said, was perceived as the domain of a “true artist,” while color photography was interpreted as “commercial or even whorish.”6 Indeed, we saw how Antonio Lopez, keenly aware of this divide, chose the cheap Kodak Instamatic camera precisely because of the buoyant color it could solicit.

And yet, while Smith was a black-and-white believer, she seemed uninterested in portraying Jones as a proper art-historical subject or an explicitly political one. If anything, it was an economic decision, one of “making do” with limited resources. Color film had to be sent to a lab to process, making the total cost five times more expensive than black-and-white film, Smith told me.7 By situating Jones as a photographic subject within Cinandre’s voguish environment, Smith accomplished something else: Her portrait frames the artistic labor of women of color in producing beauty—in front of and behind the camera. We can imagine the reciprocity between Smith’s photographic gaze and Jones’s carefully held pose as they recognize each other’s skill and subjectivity on both ends of the camera lens. In short, their friendship became the fulcrum of this fruitful and spontaneous encounter. In the midtown hair salon, rather than Barboza’s studio downtown or a more traditional art space uptown, it was another instance of subverted expectations about where collaborative and edgy art-making occurred. Finally, while the photograph ostensibly lacks color (despite its interplay of soft gray, white, and black shades), it is a reminder that color, regarding race, was the basis of Jones and Smith’s marginalization in the fashion industry. In other words, while color was aesthetic, in the artistic sense, it was also profoundly politicized, an unending marker of racial difference—and also, for Smith and Jones, of mutual support and determined connection.8 As José Esteban Muñoz reminds us, by way of W. E. B. Du Bois, “feeling like a problem is also a mode of belonging, a belonging through recognition,” which is a perfect description of their shared commonality.9

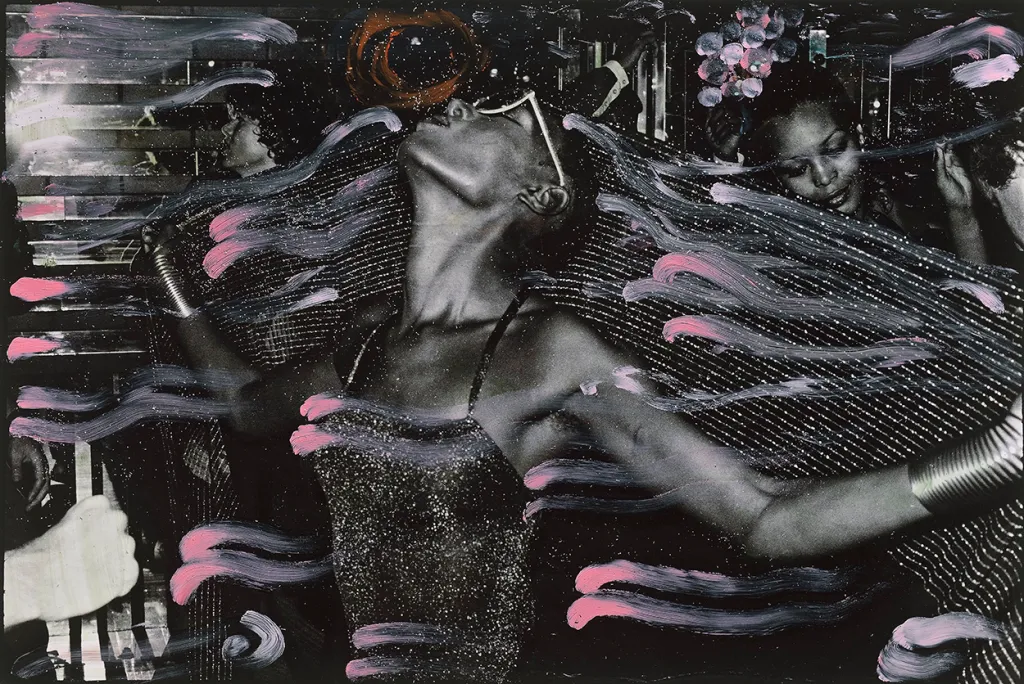

Grace Jones at Studio 54, New York, 1978

Ming Smith

Several years later, in 1978, Smith photographed Jones again at yet another fashionable site: Studio 54. By this time, Jones had become a singer (with two disco albums to her credit) and a breakout star: her 1975 single “I Need a Man” became her first number-one on Billboard’s Hot Dance Club Songs chart when it was rereleased in 1977, attesting to its popularity with nightclub djs. The occurrence of the photograph was, again, sporadic. “She called me and said, ‘Bring your camera!’” Smith said. Fresh from Paris, where her modeling career had taken off, Jones was “returning to New York as a success.”10 That sense of triumph was evident in the photographic magic Smith and Jones conjured. In Grace Jones, Studio 54, Jones is seen in profile, artfully staging herself. She is wearing sunglasses, piles of metallic bracelets on each arm (the same ones, it seems, she wore while posing for Antonio Lopez’s Candy Bar Wrapper Series), a Lurex-like camisole, and a coordinating long scarf, which rests on her head. At the same time, its ends are held in each of her hands. Light reflects off her skin at various contact points—collarbone, neck, cheekbone—and her mouth is slightly ajar. If you look closely, two oblivious Black patrons are visible behind Jones on the right side of the image. However, the hip setting of Studio 54 is not visually apparent because Jones’s elongated scarf takes up most of the photographic space, becoming a pliable aesthetic object.

In contrast to the aspiring model that Smith photographed in Cinandre, this incarnation of Jones is closer to the disco diva who still stimulates our imaginations, the perpetual performer who flamboyantly wields artifice. After all, as writer Ramon Lobato reminds us, excess is a quintessential component of Jones’s body of work, where the “abundance of style becomes the work’s substance.”11 Jones’s adept self-staging in Smith’s photograph also suggests how Jones learned “key devices for subversive performance during the 1970s in the worlds of Parisian fashion and New York disco,” art historian Miriam Kershaw writes. These dramaturgical strategies included how to “give movement and costuming maximum visual impact,” reinventing the self through “rapid modifications of external appearance” and enthralling audiences with “artifice and constructed effects.”12 Jones’s configuration of herself here also illustrates how “the medium of photography necessarily relies on the performance of the photographed subject,” as Joshua Javier Guzmán and Iván A. Ramos succinctly put it.13

Yxta Maya Murray, who argues that Smith’s photographs also drew “from her life as an aestheticized and objectified woman of color,” interprets the photograph’s glimmering elements as evidence of Jones’s manipulation of glamour and Smith’s alliance of dance and photography.14 “Less posing than unfurling herself before the camera” is Murray’s apt description. In the interplay of light bouncing off the various metallicized finishes of Jones’s accessories and clothing and her skin, we see glamour as a “weapon and power source that Jones embodies with her seemingly unvanquishable gift for movement. Indeed, Jones’s almost flamenco contrapposto speaks to Smith’s lifelong interest dance.”15 Specifically, Smith began taking dance classes in New York City after learning about choreographer-anthropologist Katherine Dunham, whom she cites as one of her artistic forebears. Smith has also described the quick adjustments employed while walking down a runway as identical to trying to grab that decisive moment in the frame.

Smith, like Antonio Lopez and his compatriots, and like Grace Jones more and more, ignored disciplinary boundaries. Instead, she imagined—and willed—a loose continuity between modeling, dance, and photography. Hence, we can interpret Smith’s photograph of Jones in Studio 54, the preeminent site of the get-down, as hovering between these different mediums of artistic expression. This improvisational approach between Jones and Smith, working together in the spaces between seemingly distinct art forms, is another example of horizontal art-making. We can speculate further that Smith’s cross-disciplinarity urges viewers to engage the portrait through a movement approach rather than a strictly ocular one, perceiving it as dancing in place. Indeed, it is no surprise that Smith masterfully renders a fleeting sense of Jones’s dramatic movement since Smith is adamant that photographs constantly shift, even when they appear static: “The image is always moving, even if you’re standing still.”16

Furthermore, Smith’s skill in showcasing Jones’s theatrical wielding of glamour was influenced by her shared experience as a model. Smith was versed in conveying allure through gestures and facial expressions in front of the lens and on the runway. However, the “white world of fashion and adver- tising” in the late 1960s and early 1970s limited the opportunities of models of color, especially Black women, to perform glamour.17 Naomi Sims, who studied at the Fashion Institute of Technology simultaneously with Stephen Burrows, was widely celebrated in the 1970s as the first Black supermodel. Sims and Beverly Johnson, the first Black woman to appear on the cover of American Vogue (in 1974), were part of the first wave of Black models who began integrating these industries.18 Yet that select group, in the 1970s, was tiny. For instance, Pat Cleveland, a model for Ebony and Jet, the most suc- cessful Black publications, as well as the prestigious Vogue, said, “These represented two different cultures; they were like different sides of the railroad tracks, and I kept crossing over from one to the other.”19 Wilhelmina eventually reversed course and signed Smith and Jones. Smith became one of the agency’s top performers, appearing in several advertisements for cosmetic companies. Meanwhile, Jones—whose exotic look was still unsuited for catalog work—outraged Wilhelmina when she shaved her head without permission; she was forced to wear wigs while her hair grew back. Who better than Jones to understand that, in an industry rife with racism and overt antipathy toward Black women models, boldly staging yourself as an object of desire, glamour, and radiant self-possession was the ultimate transgressive act?

Smith and Jones’s joint aspirations in figuring out how to be themselves, frequently through their art, unites them with the broader constellation of characters permeating Mavericks of Style. This polyglot group shared an obstinate refusal to stay within the limits of recognizable forms.20 Their creative exploration was often a search for the optimal form to articulate a thematic concept, such as Lopez’s sudden switch to the Instamatic camera. However, Smith and Jones remind us that this inquiry was also about utilizing one’s chosen medium to express oneself in the most expansive way possible, such as carefully held facial composure or the exacting drape of a piece of glitter- ing fabric. It was an act of becoming—transforming into a bona fide artist or personifying an idea. In short, style was continually harnessed as a conduit for personal and aesthetic transformation.

This is particularly salient in Smith’s second black-and-white photograph of Jones in Studio 54, almost identical to the first, albeit adorned with flourishes of orange and pink paint. Also titled Grace Jones at Studio 54, Jones—in profile—is pictured in the same outfit, still using her long scarf as a malleable tool, with one side falling to the floor and the other extending past the pho- tographic frame. Her head is tilted back this time, and her eyes are closed behind her oversized sunglasses. Jones’s angular jawline, much more promi- nent in this image, appears sculptural. She looks blissful, momentarily lost in the sublime rhythms of an unheard song. Around her, we can see glimpses of other bodies, someone’s hand in the foreground on the image’s left side, and another’s face in profile. The most noticeable person, besides Jones, is another Black woman standing behind her, face visible over the top edge of Jones’s outstretched scarf. While this woman’s eyes are downturned, we can see the subtle smile on her face. One of her hands is suspended in the air; she appears to be snapping her fingers. The collective embodiments suggest that Smith’s photograph was taken on the dance floor. Meanwhile, a faint circular orange swirl is painted above Jones’s head, and hot pink brushstrokes, moving left to right, complement the stripes in her scarf and seem to undulate like waves.

An incredible tactile energy comes from Smith’s pink brushstrokes, their bright hue and palpable texture adding a multisensorial element to the photograph, elevating it to another realm. These squiggly lines enhance the sense of Jones’s corporeal movement, as they seem to emanate from her electrifying presence. Their “material surplus,” to use Rizvana Bradley’s language, is evident in the visible marks left by the paintbrush as it moved across the photograph’s surface and in the warm intensity of the hot pink itself.21 This effulgent shade also appears in Lopez’s Ribbon Series. Smith’s painterly sensibility imbues the photograph with a startling haptic quality; it calls us to see and touch it.22 In this sense, its visceral hapticity gestures to the painted photograph’s excess, how it spills out of the bounds of one sense and into another. This seems appropriate for the times, considering how the prototypical 1970s disco was repeatedly described as a venue that engaged multiple senses simultaneously. For instance, Roland Barthes visited the Parisian disco Le Palace in the spring of 1978, the same year as Smith’s photograph. He marveled at its fantastic unison of “pleasures ordinarily dispersed,” including dance, music, and “the exploration of new visual sensations, due to new technologies”—an insight easily applicable to Studio 54.23 Barthes’s musing could also apply to Smith’s artistic proficiency here. Her textured hot pink paint jars us out of passive spectatorship, using color to invite us into this elusive but sharply rendered world: aural ecstasy, chromatic excess, and hap- tic pleasure.

Moreover, Smith and Jones’s friendship is evident in the ease with which they riffed off each other’s energy, like musicians in an ensemble, as if Jones’s fearlessness as a model and club fixture stimulated Smith’s freewheeling artistic freedom. After all, Jones continued expanding her repertoire in this period, channeling her artistry into a newfound music career, where her “appearance, musical taste, and sense of fashion in many ways shaped the image and public perception of disco.”24

Meanwhile, Smith experimented with painting and blurring her photographs—an instinct-driven, ad-lib method that differentiated her from her purist peers in the Kamoinge Workshop. In doing so, she developed a more poetic, dance-inflected approach to photography—driven by light, beauty, and energy—that has become her signature. Put differently, Smith has mastered “a singular and technically challenging style: Her images shake and soften the lines between the subject and its background, mimicking movement itself.”25 Smith and Jones’s camaraderie underpins these portraits, an artistic duet in which they became their freest and most imaginative selves. And while Jones’s breakthrough as a model occurred in Paris, Smith’s big break was local: The Museum of Modern Art purchased two of her photo- graphs in 1979. She became the first Black woman photographer to have her works acquired by the institution.

We have witnessed Jones’s shift from a neophyte model to a more seasoned pro, as her respective representations have also become more layered and complex. Jones grew increasingly confident before the lens, starting with her incipient work with commercial photographer Anthony Barboza in the early 1970s. She began staging herself more theatrically, which has become her trademark. (Barboza photographed model Pat Cleveland, Jones’s equally bubbly peer, in 1977.) The portraits taken by Smith, first at Cinandre and later at Studio 54, can be interpreted as “before” and “after” shots that visibly mark the transition in Jones’s professional self-development. In this arc, we can see a simultaneous artistic change, from Barboza’s photo-editorial work for Essence to Smith’s elegiac black-and-white portrait at Cinandre, culminat- ing in her exuberant, disco-infused hybrid of hot pink paint and photography at Studio 54. Smith and Barboza’s straining of clear-cut delineations in their work—between color and black and white, or in Barboza’s case, between commercial and fine art photography—mirrored Jones’s intrepid traversal across genres and categorical imperatives.

For instance, the artsy filming of Jones’s haircut in an obscure color video from 1978 showcased the morphing of the quotidian into a fresh performa- tive event. The fourteen-minute-long video, titled Anton Perich Presents Grace Jones, Haircut (1978), opens with a close-cropped shot of hairstylist Andre Martheleur, standing in a light blue button-down shirt, before quickly zoom- ing out to show Jones sitting in a salon chair beside him.26 The camera zeroes in on her. She is wearing red lipstick, a gold chain around her neck, and a brown unzipped jacket, suggestively ajar, without a bra. She has the same closely shaved haircut with a high-cut scalp that we saw in Smith’s photo- graph at the same salon. Over several minutes, Jones and Martheleur banter with each other in French while he applies what appears to be Vaseline to her forehead and uses a pair of small scissors to trim her scalp. Around eight minutes in, Martheleur takes out a small makeup palette and begins painting something on the back of her head with a small brush. At one point, the camera pivots down to show Jones holding a small microphone in her hand while wearing a jumble of silver bangles, presumably the same ones worn in Lopez’s Candy Bar Wrapper Series.

Soon after, we see that Martheleur has painted a jagged, zigzagging gold line down the back of her head; he then starts painting one of her earlobes the same color. “You like to make me bleed . . . suffer for beauty,” Jones jokes. Randomly, she says, “Willi Smith,” before switching back to French. She name-dropped the Black fashion designer who pioneered streetwear in the 1970s and the brother of model Toukie Smith, a peer of Jones. Later, she tells an off-camera patron,“You look so different with your hair down.” After the woman audibly responds with resignation, Jones exclaims, “Come on, get it up. Get it up.” Jones laughs, playfully sticking her tongue out, amused by her sexually suggestive double entendre. When Martheleur finishes, she stands up, looks at herself in the mirror approvingly, and puts the microphone down. Then, after a quick pivot, she and Martheleur are seen standing against a wall talking, with evident mutual affection for each other, before she turns to exit the salon-cum-stage.

Regarding genre, this video moves beyond easy classification into some- thing less defined and amorphous. While it certainly exceeds the simple doc- umentation of Jones’s haircut, it frustrates any further desire to categorize it. Is it video art, a salon-based “happening,” or something else? There is no clear-cut answer, as it could be all those things. And yet, in the context of our discussion on the staging of glamour, Anton Perich Presents Grace Jones, Haircut reveals a type of fashion performance in which beauty is carefully calibrated and physically produced. In short, it becomes a verb, a doing, rather than a noun. Beauty is a performative act. It is often refined through the input of others, a fact embodied in the working relationship between Jones and Martheleur. After all, Jones has described his skill in artistic terms elsewhere, stating that he “created paintings in my hair” and “treated my hair as though he was producing a sculpture, with incredible attention to detail.” She adds, “He was more than a hairdresser. He was an artist…very experimental.”27 The video captures an “interaction-in-the-making,” to use Michelle Stephens’s words—an unfolding event rather than a onetime occurrence with a finite endpoint.28 Jones’s quirky magnetism is so strong that she single-handedly transforms the seemingly banal act of a haircut into a captivating display of her charisma. And when we see her smiling face reflected in the sa lon’s mirror as Martheleur gracefully touches up her hair, she reminds us that the performance of glamour is not simply a honed skill but also a site of joy.

Endnotes:

1 Grace Jones, I’ll Never Write My Memoirs, 79.

2 Ming Smith, personal communication with the author, July 28, 2023.

3 Ming Smith, personal communication with the author, July 28, 2023; Jones, I’ll Never Write My Memoirs, 107.

4 Ming Smith, personal communication with the author, July 28, 2023.

5 Galvão, “View from: Ming Smith,” 30.

6 Ming Smith, personal communication with the author, July 28, 2023.

7 Ming Smith, personal communication with the author, July 28, 2023.

8 I am thinking of Johana Londoño’s discussion of chromatic color versus color as “racially ethnically, spatially, and politically significant.” See Abstract Boarrios, 71. See also Darby English’s “artifactual color,” a “sense of color generated in the tension between color’s racial connotations and its aesthetic meanings,” in 1971, 9.

9 Muñoz, Sense of Brown, 37.

10 Ming Smith, personal communication with the author, July 28, 2023.

11 Lobato, “Amazing Grace,” 135, 136.

12 Kershaw, “Postcolonialism and Androgyny,” 19, 20

13 Guzmán and Ramos, “Mediated Identifications,” 26.

14 Murray, “Beauty Is in the Eye,” 127.

15 Murray, “Beauty Is in the Eye,” 128, 129.

16 Smith and Talbert, “Portrait of the Artist,” 15.

17 Brown, Work!, 231.

18 Detroit-born Peggy Ann Freeman, known professionally as Donyale Luna, was a precursor to both. She became the first Black woman to ap- pear on the cover of any edition of Vogue, gracing the British edition in March 1966, and enjoyed wide success in Europe. See Powell, Cutting a Figure; and Brown, Work!

19 Cleveland, Walking with the Muses, 152.

20 For more on waywardness as a form of Black feminist refusal, see Hart- man, Wayward Lives.

21 See Bradley,“Introduction.”

22 For more on “haptic visuality,” see Marks, Skin of the Film.

23 Barthes, “At Le Palace Tonight . . . ,” 48.

24 Quoted in “Portfolio II: Can You Feel It? Creating Environments and Experiences: Light and Sound Technologies,” in Kries, Eisenbrand, and Rossi, Night Fever, 166.

25 Gyarkye, “Ecstatic, Elusive Art.”

26 Anton Perich Presents: Grace Jones, Haircut, filmed haircut with Andre Martheleur, Cinandre, New York, 1978, posted May 24, 2022, by Anton Perich, https://youtu.be/_ED-vLWemWU.

27 Jones, I’ll Never Write My Memoirs, 83.

28 Stephens, Skin Acts, 85.