I never thought I’d get misty-eyed reading an essay called “Why I Am an Asshole,” but artists are always surprising me, and that’s why I love my job. This tragicomic tearjerker, from 2021, appears in Joseph Grigely’s new essay collection Otherhow: Essays and Documents on Art and Disability 1985–2024. The book made me laugh and cry, and it made me angry, too—angry alongside, rather than at, the author. I felt seen. I learned lots.

You’re probably wondering: Why is Joseph Grigely an asshole? His short, self-deprecating answer is that he is fed up, as a deaf man, with navigating ableism, with overcoming the same obstacles again and again. Sometimes, that frustration shows. And sometimes, when people—strangers, pizza delivery workers, police officers—try talking to him and he doesn’t reply because he cannot hear, they grow angry or annoyed, or even try to arrest him.

The asshole essay originated as a preemptive apology to students while guest lecturing on Zoom. He was asking for their patience as he eyeballed several screens to keep track of his interlocutors, his interpreter, and his presentation simultaneously. He showed a screenshot of the software’s captions and access disclaimer: “our products are compliant, with exceptions.” Somewhat inured to this typical truth—to things being accessible-ish—he laughed it off. At least Zoom is honest.

A page from Joseph Grigely’s 2026 book Otherhow: Essays and Documents on Art and Disability 1985–2024.

Courtesy Primary Information

Assholery aside, for most of the book, we watch Grigely carefully convert his anger—as well as his expertise and experience—into calculated and constructive criticism and advocacy. There are persistent, pleading emails to curators requesting, for instance, a sign language interpreter who might accompany him to the opening of the 2000 Whitney Biennial. (This request was denied, even though his work was included in the show.) There are xeroxes of several lawsuits with details heavily redacted, respecting requisite NDAs. There are unpublished op-eds rejected by the New York Times, shown alongside collections of the paper’s ableist headlines incessantly wielding blindness and deafness as metaphors for ignorance. And there are postcards addressed to the artist Sophie Calle.

It is these postcards that open the book. They comprise a text I’ve returned to many times in my life, always admiring the calmness and curiosity they retain in gently pointing out all the ableism in Calle’s “The Blind” (1986), a work where she photographed blind people and paired them with their descriptions of beauty. In the postcards, we watch Grigely work out his thoughts about her photographs, which he can’t seem to shake, as he challenges her softly. He points out that the series is wholly inaccessible to the population it depicts, that the work both romanticizes and others its subjects. Calle was admirably receptive, first meeting with Grigely and then arranging to have the postcards published in Parkett.

As you may have already noticed, the ephemera of correspondence—postcards, xeroxes, and emails—is Grigley’s medium. For him, art, writing, and autobiography merge into one, both in this book and throughout his practice. That’s because writing is inseparable from his everyday life. When conversing with people who do not sign, he passes notes; he does not read lips because, he memorably points out, “vacuum” looks exactly like “fuck you.”

Over the years, he has amassed a veritable archive of banal conversations ordinarily lost to the ether, saving scraps from casual chats. He calls the results rhopography—depictions of the trivial and the everyday. And this material mode of communication is as enabling as it is disabling, allowing for flirtations and gossip and dirty jokes to be exchanged out in the open, like “playing footsie on top of the table.”

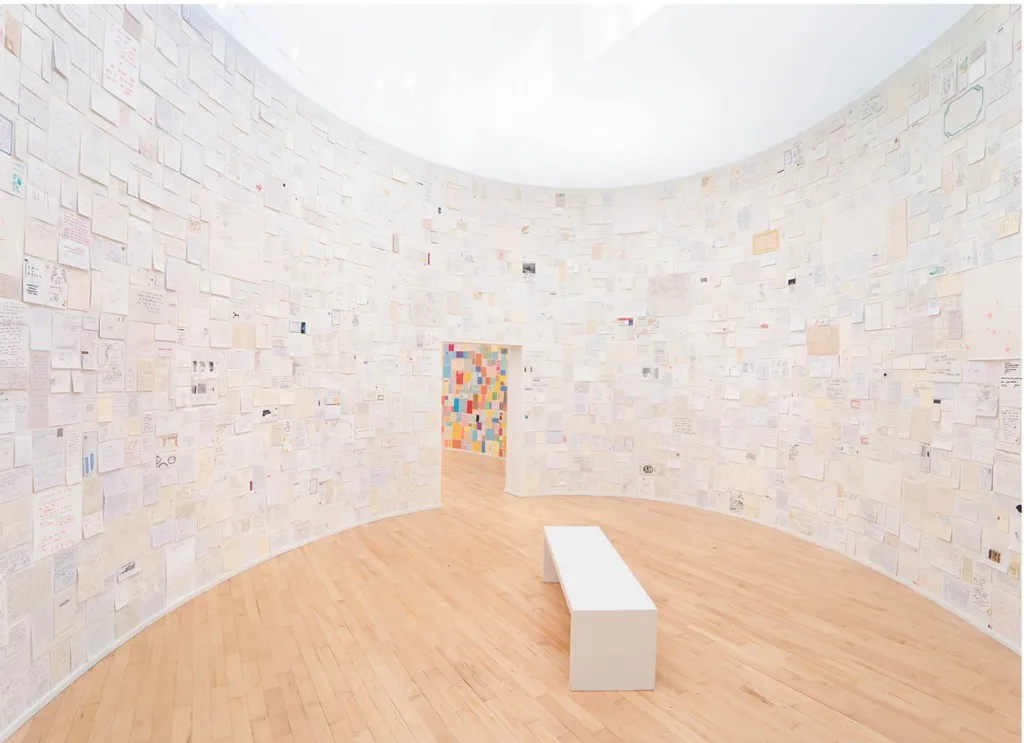

For 30 years, Grigely has turned his archive into artworks. His first note-based Conversation Piece premiered at White Columns in New York in 1994, and more recently, he arranged about 20,000 notes for a work called White Noise (2023). In this installation, two ovular rooms form an infinity shape. In one room, the walls are plastered with notes on white paper. The other boasts a radiant rainbow of scrap sheets dominated by a Post-it palette. The titular auditory term, “white noise,” draws its analogy from color theory, describing simultaneous sounds that cannot be parsed into distinct decibels just as white light contains the full spectrum of hues.

Grigely’s project proposal, reproduced in the book, includes more color theory still: “Remember how Albers said you can’t put one color beside another without affecting both?” he asks. “It’s like that with words.”

This is not to say the book is all—or even primarily—tidbits and notes. As an essayist, Grigely is just great, among the most articulate artists of our times. Probably, it helps that he has a PhD in English from Oxford, and that he’s had to pay attention to written language more than most.

Dr. Grigely earned his bona fides despite barely making it through high school. As a teenager in Massachusetts before the 1990s Americans with Disabilities Act, it was hardly worth attending class; he couldn’t hear what the teachers were saying. His parents understood when he’d skip to go fishing.

Somewhere along the way, he got into books, eventually writing his dissertation on the poet John Keats. After school, on the academic track and teaching at Stanford, he found that the art world he stumbled into was somewhat easier to deal with, access-wise. It relies on individuals more than bureaucracy and committees, and he reasoned that “If I could convince individuals of my worth—not just as an artist but as a human being—I stood a much better chance of finding a platform for sharing my work.”

Notice how he mentions proving his worth as a human with devastating nonchalance, em-dashes not withstanding: proof he’s had to do it far too many times.

Yet almost always, he ends his essays on a joke, no matter how angry or difficult, how formal or playful it might be. Maybe that’s strategic; maybe it’s just his personality. But even an awful, true story about a downright dangerous kerfuffle with the MIT police ends in a punchline stranger than fictsion. Meanwhile, the artwork that best captures his frustration is also probably his funniest. For Between the Walls and Me (2023), he cast a copy of his own head, then banged it against the drywall until it did some damage.

The book is a portrait of an artist balancing unapologetic anger and the sobering knowledge that you catch more flies with honey than vinegar. Grigely, for his part, is a master fly fisher, both literally and figuratively.

Here, I must add gratitude to the list of emotions this book elicited in me. Even when it went unstated, I could sense all the exhausting, repetitive labor of advocating for basic access, even human worth. I could recognize and relate, and yet I know that, in many ways, I have it easy compared to Grigely and his generation; they did so much of the groundwork with far fewer tools. Today, it’s difficult—but honestly, still not especially difficult—to imagine the Whitney denying an interpreter request. (The museum’s exemplary access department was started in 1994, but was geared toward visitors more than artists; similarly, as Grigely notes, university access departments typically serve students and not faculty.)

Over the decades, the artist has had to make the same points again and again—proof that though the world may be largely hearing, that doesn’t guarantee that people listen.