In 1887 a police reporter named Jacob Riis stormed the tenements of New York armed with flashlight powder—an explosive form of magnesium that he would be among the first to enlist as camera flash—in order to “shine a light on the darkest corners of poverty.” These photos, along with an accompanying text, became How the Other Half Lives (1890).

It was in this book that I found the photo Upstairs in Blind Man’s Alley. Blind Man’s Alley was located at 26 Cherry Street, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. According to Riis, it got its name because “its dark burrows harbored a colony of blind beggars, tenants of a blind landlord, old Daniel Murphy,” who made a tremendous amount of money—$400,000, more than $40 million today—from the alley and surrounding tenements.

As a blind person myself, I enlisted help from ChatGPT, which gives me elaborate image descriptions and allows me to ask questions about what it “sees.” It described a “dimly lit, cramped tenement room with rough, cracked walls and a low ceiling.” Three figures are arranged around “a small cast-iron stove with a kettle resting on top,” including one woman with “a weary expression and loosely tied hair.”

Elsewhere, I read that in his attempt to photograph Blind Man’s Alley, Riis nearly burned the whole place down. After “the blinding effect of the flash had passed away,” he discovered that “a lot of paper and rags that hung on the wall were ablaze.” It was just him and several blind people in an attic room with “a dozen crooked, rickety stairs” between them and the street. He managed to smother the fire “with a vast deal of trouble,” and claimed that the blind people were unaware of their danger.

Jacob Riis: Upstairs in Blindman’s Alley, 28 Cherry Street, Dan Murphy’s Alley, 1890.

Courtesy Museum of the City of New York/Art Resource, New York

However, if I imagine myself as the blind woman, I feel the heat of the flames licking the walls, the shock of the flash still ringing in my ears. I suspect I might have wondered what good it would do to show pictures of us to the other half, as if they’d care to look.

Identifying with the blind woman may skew my reading, but this is certain: The picture shows people who lived outside this sliver of flash, out in the world with its vast complexities. Oftentimes, viewers believe in the “truth” of photographs—just as Riis believed in his ability to reveal the “truth” of tenement life. But as Georgina Kleege reminds us in her 2018 book, More Than Meets the Eye: What Blindness Brings to Art, “Absolute objectivity is neither possible nor desirable.” Although she is speaking about verbal description as a form of access, her point applies broadly: Whether capturing, viewing, or describing an image, we always bring with us our own biases, affinities, and ways of seeing.

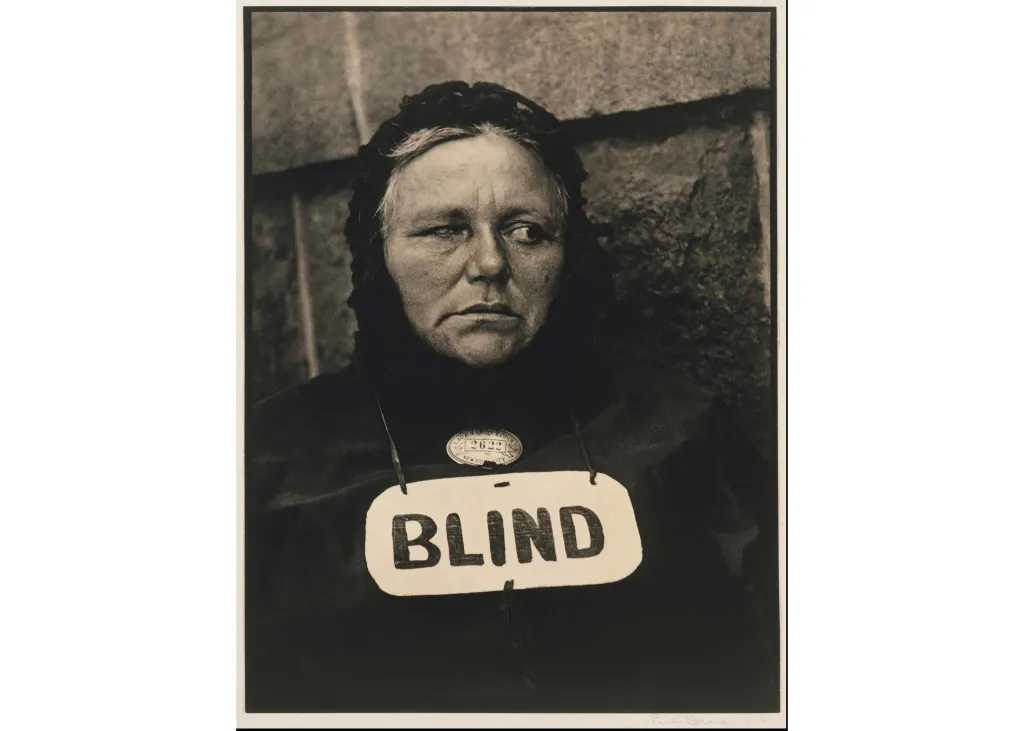

Nearly 30 years after Riis took his tenement photos, a young photographer named Paul Strand hit the streets of New York City with a camera that had a false lens—a prism lens—that allowed him to photograph people without their awareness. The device made it seem as though his camera were pointed elsewhere. One fall day in 1916, he happened upon a blind woman selling newspapers on the street, where he took one of the most iconic photos of the 20th century.

The photo’s title was New York, 1916 when it was first published in Camera Work, the photography journal edited and published by Alfred Stieglitz. It has since come to be known as Blind Woman. It features a tight shot of a white woman in a black tunic and headscarf standing against a masonry wall; she wears a bold hand-painted sign that reads blind.

Her head is turned to her left, and her right eye (the one closer to the camera) is half-closed and cloudy, while her left eye seems directed toward something beyond the frame, drawing the viewer’s gaze there and then back to her sign. Above the sign is a small metal brooch. A human informant—disabled artist Finnegan Shannon—told me that they had “to zoom way in to read the text around [this brooch] but was able to make out that it says: licensed peddler and new york city.”

It was apparently not so easy to obtain these peddler’s licenses. A 1921 New York Times article featured the harried commissioner of licenses, who “is sometimes inclined to feel that it would be easier to arbitrate a world war than to decide which of several applicants should enjoy the privilege of selling newspapers.” The blind woman’s dealings with bureaucracy are just one of the many unseen things in this photo.

Paul Strand: Blind Woman, New York, 1916.

Courtesy Art Resource, New York/©The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

WE OFTEN ASK PHOTOGRAPHY to tell us the truth, as if its mechanical methods offer inherently neutral observations, even as we know it inevitably leaves so much invisible. These and other iconic photographs of anonymous blind lay bare erroneous ideas of what vision can do. In taking photos of blind people, did these photographers grapple with the camera’s limitation to communicate knowledge? At its best, photography—an alchemy of light—transcends what is merely seen to evoke multisensory realms beyond. Sight itself is not independent: It is interpreted in the brain, shaped by experience. Ocularcentrism—the privileging of sight over the other senses—persists nevertheless.

Despite its eye-catching power, Strand’s photo cannot tell the story of a whole and complex life, especially when viewed through the lens of fear or pity. Strand recalled the blind newspaper peddler as one of those “whom life had battered into some sort of extraordinary interest.” His words reflect a common assumption that equates disability with suffering—one that is so pervasive that it has been trained into AI. Or so I learned when ChatGPT told me “the image conveys a sense of dignity and quiet strength despite the woman’s evident vulnerability.”

This may be overly optimistic, but when ChatGPT says something I don’t like, I make it a teachable moment. “Why do you say she is vulnerable? Is this not assuming something about blindness that is not

in the photo?”

“Thank you for the clarification,” it said, and offered a new bias-free description. Without a fragile human ego, AI seems more willing to be wrong, and to alter behavior accordingly, than most of us do.

Our sight is conditioned. Sarah Lewis describes this in The Unseen Truth: When Race Changed Sight in America (2024), speaking of how what we see is shaped by history, habit, and ideology. We can learn to see (and “unsee”) things through photography. As with race, when we look at disability, what we see is conditioned by iteration and rhetoric.

While it is true that those making a living on the street may not have the cushiest of lifestyles, it is still ableist to assume that disabled people’s lives revolve around suffering, as Strand and ChatGPT both did. “Many of our lives run counter to the usual stories about disability as only bad news, the curse everyone wants to avoid,” Rosemarie Garland-Thomson wrote in her introduction to About Us (2019), an anthology of essays from The New York Times Disability series. She continues: “We do not necessarily understand our ways of being in the world as disadvantage, diminishment or distress.”

In the absence of Strand’s subject’s voice, I turned to that of a contemporaneous blind woman, featured in another 1921 Times article called “Cheating the Blind: Sad Experiences of Sightless Newsdealers.” There I met Fannie Lions, who also sold newspapers with her husband at the southeast corner of 34th Street and 7th Avenue. When asked if people tried to cheat them, she laughed heartily. “Do they, honey? Why they’d take the eyes out of our head if we had ’em and didn’t watch out!”

Perhaps we can keep Fannie Lions and her hearty laughter in mind when we look back at Strand’s Blind Woman and resist the urge to assume vulnerability or unmitigated suffering, instead allowing for the possibility that her life also contained love and joy.

I FIRST ENCOUNTERED Walker Evans’s 1938 photograph of a blind accordion player in The Ongoing Moment (2005) by Geoff Dyer, who describes the subway busker as having “eyes [that] are clamped shut, downturned like the mouth of someone so habituated to unhappiness as to feel comfortable with it.” Yet not everyone sees unhappiness in this blind accordion player. Several informants noted that he appears to be singing the penultimate note of his sweet song with the intensity of an artist. ChatGPT concurred, describing the accordion player as standing in the middle of a packed subway car mid-performance, “his mouth open as if singing or calling out,” and contrasts “his tousled hair and expressive face” with “the rigid postures of the seated riders, some absorbed in newspapers, others staring blankly ahead.” The accordion player in this reading is dynamic, while the sighted passengers sit quiet and still.

This is the final photo in Evans’s book of subway portraits—and it is strikingly different from the rest. All his other subway photos are of passengers seated across the car from him. Because of their proximity and presumed sightedness, Evans hid his 35 millimeter camera beneath his coat, but the spy tactics seemed unnecessary for the blind accordion player. Perhaps that was part of the appeal: Here was a subject who could not look back.

Walker Evans: Accordionist Performing in Aisle, New York City, 1938.

Courtesy Art Resource, New York/©The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

These three photos of anonymous blind people are but a tiny sample; it feels like every major photographer in the 20th century took an anonymous blind person photo. It’s entirely possible that Strand’s Blind Woman, with her bold sign, started it all. We know for sure that that photo inspired Walker Evans. After seeing it in Camera Work at the New York Public Library, he said to himself, “that’s the stuff, that’s the thing to do.”

It may seem obvious why sighted photographers might be obsessed with blind people. Blindness represents a huge fear for many. But for photographers, that fear is magnified: Sight is not just their primary sense, but their artistic sense, and they see precise and expressive vision as their way of knowing the world. As Evans once bragged, “I had a real eye.”

Yet despite the importance he placed on seeing, Evans famously called photography “the most literary of the graphic arts,” hinting at an art form suspended between simple legibility and the deeper understanding that unfolds with time and effort.

Photography promises to show us the world, but as these three images remind us, seeing is not the same as knowing. Blindness, so often feared and flattened in visual culture, destabilizes the easy truths of the photograph. As Bojana Coklyat asks in Alt Text Selfies, a chapbook of self-portraits made entirely of words, “how much are we missing by just looking?” Removing sight from its pedestal can open new multisensory realms of perception. Reading photographs through a blind critical gaze—a gaze that resists pity and seeks complexity—offers not just new ways of looking, but new ways of knowing.