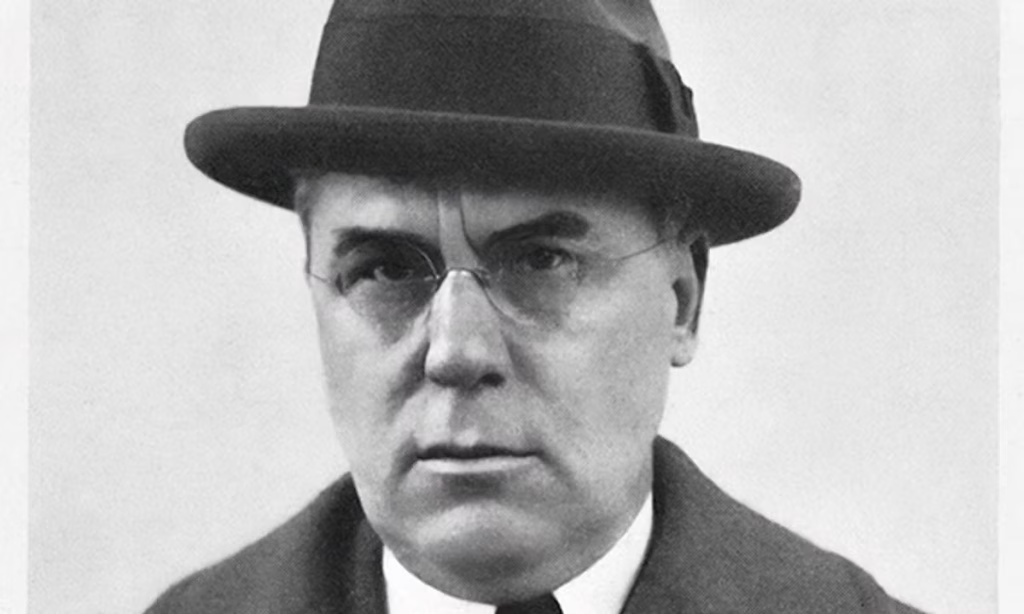

In 1951, Albert C. Barnes sped through a stop sign at a crossroads in Pennsylvania. His Packard convertible collided with a tractor trailer loaded with paper. The Philadelphia art collector, aged 79, and his dog were killed.

Barnes was irascible, obsessive and rich. He built a collection with more Paul Cézannes than anywhere else in the US, with exceptional early Picassos and room after room of Renoirs. In 1912, he was the first American to buy a painting by Vincent van Gogh, The Postman (Joseph-Étienne Roulin) of 1889. He also acquired Henri Matisse’s serene Joy of Life (1906) and commissioned the artist to paint the radiant gallery-sized mural The Dance (1932-33). Nothing else in the US came close.

Shooting from the hip defined Barnes, a physician and chemist who paid for medical school by winning boxing matches. Frustrated as a doctor but insisting on that title, he studied chemistry and developed a silver-based treatment for gonorrhoeal blindness and other ills. The man backed up his business acumen with threats, bribes and a volcanic temper. He was also multilingual and passionate about the art that inspired him. The art critic Blake Gopnik retells enough old stories and produces some zany details to give Barnes’s biography the feel of a screwball comedy—Barnes’s own version of The Philadelphia Story—until its sudden end on the highway.

In The Maverick’s Museum: Albert Barnes and His American Dream, Gopnik reminds us that Barnes’s dedication to collecting, backed up by his fortune, was genuine. So was his commitment to education, guided by the American philosopher John Dewey, one of the few people who remained his friend for life. Barnes also had a lifelong commitment to racial equality, rare in the then-segregated “City of Brotherly Love”.

The building that Barnes opened in 1925, just beyond Pennsylvania’s city line, exhibited Post-Impressionist paintings, African sculpture, contemporary American art and Old Masters (of questionable attribution), often displayed between metal industrial hinges, which he also collected. The book’s title notwithstanding, Barnes did not create a museum, but a foundation for art appreciation.

Shocking polite society

Gopnik writes gracefully as he follows the parallel lines of Barnes’s rough-and-tumble acquisitions in France from 1912 and his rigid formalist theories influenced by Dewey. That approach ignored the subject matter of the works that he showed. “For Barnes, that art itself, however deluxe and elite, represented the possibility of egalitarian new beginnings…; it stood as a reminder of his own rise out of grimmest poverty and as a symbol of the ascent that he desired for others,” Gopnik writes.

Barnes shocked the polite folk of Philadelphia by exhibiting nudes, among many other sins. One newspaper gathered a panel of physicians to conjecture on which pathologies had led him to do so. The collector, a working-class kid expecting scorn from the “well-born”, loved the fight: the more vituperative the better. While Barnes was alive he had plenty of money and some allies, so he got away with doing what he pleased. That said, as Gopnik notes: “His grim intemperance did lasting harm, in distracting from the real substance of Barnes’s achievements, ideas and even character…for some observers, his virtues have remained hidden. He has come off as a fool, a monster, or both”.

Barnes’s many adversaries would launch another fight, soon after his death, to open his collection to the public, while Lincoln University, a historically Black institution that Barnes named, eventually controlling the board, was shamed out of selling works from the collection to create a patronage fund. A court eventually permitted the loan of works from the Barnes Collection for a travelling show, an arrangement that the man himself would never have allowed. Money problems and pressure to promote tourism led to another court decision allowing the foundation and collection to decamp from suburban Merion to a new, crowd-friendly building near the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

It took a character like Barnes to form his extraordinary collection (plus the many restrictions he placed on it). It later took years of battling in court for politicians, their donors and Philadelphia’s cultural elite to supplant it all. The result, finally, is a museum that Barnes never intended: a Barnes without Barnes. In a brief epilogue composed like bullet points, Gopnik suggests that the larger crowds make it all worthwhile. But readers who get to this point will have a sense of the uniqueness that has been lost as a result.

Blake Gopnik, The Maverick’s Museum: Albert Barnes and His American Dream, Ecco/Harper Collins, 416pp, $35/£28 (hb), published 18 March/8 May

• David D’Arcy is an art critic, journalist and regular contributor to The Art Newspaper