It was a cold January afternoon when 35-year-old Czech artist Klára Hosnedlová arrived in London to install “Echo,” her debut solo show at White Cube (on view at the gallery’s Bermondsey branch through March 26th). Technicians with forklifts worked in the background, building the latest of her imagined landscapes: enigmatic mixed-media environments embedded with cultural and historical references. As we walked around, I felt like I’d landed on a strange new planet. Yet Hosnedlová’s work always begins with an assessment of her site’s existing structures. “It’s to feel the space, to feel its architecture and energy, to play with how I can occupy and change the emotion of the space, in a fragile way,” Hosnedlová said. “For me, the artwork always connects with the space.”

At the start of her career, before galleries were interested in her work, Hosnedlová had to serve as her own location scout. A decade ago, she presented a series of embroidered canvases depicting fragments of women’s bodies inside a home in Pilsen, Czech Republic, which was designed by famed modernist architect Adolf Loos. But in the past few years, her site-specific installations, simultaneously grand in scope and delicate in tone, have sprung up at increasingly high-profile institutions. Since White Cube announced its representation of the artist in 2022, she has presented solo exhibitions at the Kestner Gesellschaft in Hannover, Germany, Kunsthalle Basel, and Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin. In late March, when New York’s New Museum reopens to the public, her newest commission will anchor the atrium stair.

Hosnedlová, who lives and works in her small hometown of Uherské Hradiště, Czech Republic, is making the most of these international opportunities. In Bermondsey, she has taken over two galleries in the cavernous former warehouse. An enormous tapestry composed of thick strands of woven flax, linen, and hemp hangs from the ceiling of the smaller gallery. These matted tendrils, tinted with natural dyes in earth tones, are a recurring motif for Hosnedlová; she is drawn to materials that bring an organic vitality and meaningful provenance to her often stark venues. The fibers come from the last remaining linen factory in the Czech Republic; the pieces were woven by artisans at a Slovenian textile studio dedicated to preserving the region’s cultural heritage. Hosnedlová invited me to feel one of the faux locks, which was surprisingly soft and airy. The artist loves it when visitors want to touch her work, though institutions rarely allow it.

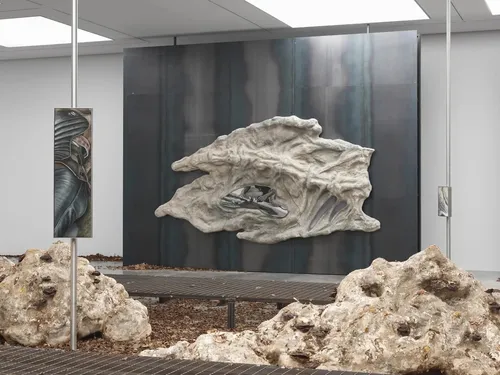

A resin sculpture, coated in stone and mineral dust, nestles in the center of the tapestry. It resembles an ancient fossil and gestures towards Hosnedlová’s fascination with remaking the past. And in a niche of the sculpture, a small, curved panel of embroidery appears, recalling her own creative beginnings—needle and thread in fact led Hosnedlová to artmaking. “When I was a child, I often made clothes for myself and my family, and I always felt so relaxed,” she said. But when she arrived at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, in 2009, she found herself in an extremely “old-fashioned” and male-dominated environment. Craft-based practices weren’t taken seriously. Hosnedlová attempted to conform to the dominant trend for abstract painting but quickly realized that “if I wasn’t enjoying the process, there was no point.” She reverted to her origins, developing her unique strategy for defamiliarizing a centuries-old craft tradition.

Hosnedlová bases her cotton-thread embroideries, which take months to complete, on photographs. Every time she has a show, she privately stages a “performance”—no spectators allowed—in which she directs participants to pose within the space. For Hosnedlová, the shots of these events are akin to drawings in a sketchbook. They’re also, perhaps, a way to connect the embroidered surfaces to her three-dimensional, total environments (or Gesamtkunstwerke, as Hosnedlová puts it): they offer a sense of continuity in her practice. The results are finely detailed, hyperrealistic images featuring fragmented glimpses of human figures frozen mid-action. A pair of hands hold a lit match; a grinning mouth exposes a full set of shiny grillz.

At White Cube, 13 additional embroideries appear in the even more elaborate mise-en-scène of the larger second gallery. Some are again on biomorphically shaped panels embedded in resin sculptures. Here, they’re mounted on a series of rolled steel screens placed like stage curtains in front of the gallery walls. Others are affixed to poles which Hosnedlová has installed in the center of the room, along with a four-sided step platform. The set-up is reminiscent of a futuristic theater in the round. (When I returned for the opening, bits of costume and other remnants from the private performance had been left behind—a leather corset sewn together with strands of textile, markings on the walls, and so on.) “I usually don’t like to arrange things around a center like this,” Hosnedlová said. “But this space has a very strong center, and there are various rectangular shapes: the shape of the room, but also the overhead lights.”

In the middle of the poles, scattered autumnal leaves surround a trio of pale, Styrofoam blocks wrapped in hemp. Mycelium and sprouting fungi emerge from their craggy surfaces. For several months, Hosnedlová cultivated reishi, a mushroom used in Eastern medicine, in a rented studio. “Years ago, I studied with a very old man, an expert reishi forager,” she said. She decided to bring fungi into White Cube when she first saw the windowless, overhead-lit space and likened it to an “underground laboratory.” Hosnedlová has incorporated the sounds of the growing mushrooms into an accompanying audio piece made in collaboration with the experimental composer Billy Bultheel.

Each venue presents a new opportunity for Hosnedlová, and she also sees her work as an ongoing process. Aspects of one project always feed into the next: several of the woven works, for example, featured in her Hamburger Bahnhof show, and photographs taken here will reappear in future embroideries. “For me, it’s important in developing myself,” Hosnedlová said of her recursive approach. It’s a way to come back to questions in her practice that remain unresolved. Hence the title of the exhibition: “Echo.” The space is the container for the artist’s voice, which will reverberate in the world beyond.