THE STUDIO MIGHT reasonably be described as the ground zero of West African photography. There, trained professionals, typically men who had chanced on studio photography as a career, devoted themselves to picturing their clientele with ardor and originality. Malick Sidibé is the epitome of this model. The late Malian photographer made images of his Malian country-people that have, since the 1990s, become venerated as art objects, less as the individual keepsakes they were initially meant to be, but as bona fide documents of a collective identity. In fact, in almost every essay about his work—or about other West African photographers with similar practices—one can find a version of the idea that he “pictured people as they wished to be seen.”

I exaggerate, of course, but only to point to the unique achievement of the late photographer’s oeuvre. His checkered black-and-white studio backdrops and his clients’ sanguine poses have become emblematic of the visual vocabulary by which African portrait photography charted its own peculiar contribution to the medium.

Sidibé (1935–2016) was by his own recollection an excellent draughtsman, and received acclaim for his talents at school. He drew flowers on pieces of fabric that were then embroidered by young girls, put in envelopes, and sent to top colonial civil servants. At the outset, his mother, who was a decorator of huts, partly inspired his interest in art. “There is a certain pride,” he said in a 2008 interview with Jerome Sother, “in imitating nature.”

Very Good Friends in the Same Outfit, 1972/2008.

An army major took notice of Sidibé’s talents, and in 1951 or ’52, sent him to the School of Sudanese Craftsmen (Maison des Artisans Soudanais), in Bamako, Mali’s capital. While there, the school principal recommended him to French photographer Gérard Guillat, who wanted a student to paint his studio. Seeing his skill with the paintbrush, Guillat asked if being a photographer interested him. “I leapt on it straightaway,” Sidibé said in the interview with Sother. “I was used to working with pictures. I found that the camera was a lot faster than a paintbrush. So I threw myself into photography and that’s how I became a photographer.”

HIS CAREER REALLY began in 1957, when he covered events for locals, like weddings and christenings, as opposed to the European gatherings his employer covered. By then he had his own camera, a Brownie Flash, and its convenience ensured his mobility. Sometimes he’d cover four parties in one night. (His older compatriot, Seydou Keïta, was meanwhile encumbered by his bulkier plate camera.) Working those parties, the overall aesthetic of his work came into focus. He photographed a nation under a groove, to paraphrase the title of a 2010 Guardian interview with him. By 1962, he ventured out on his own, opening Studio Malick, which he described as a “studio like no other … relaxed.” He slept in the developing room, sometimes developing up to 400 photos a night.

Malick Sidibé: Christmas Eve (Happy Club), 1963/2008;

The photographs from that era record a youthfulness not wasted on the young, to reformulate Chris Marker’s phrase. It was a unique era, Sidibé admitted. An ordinarily conservative youth wore fashionable Parisian attire. Boys could use the excuse of music to dance close to girls after showing off their Vespas. All this happened within the context of a newly independent Mali.

An oft-repeated Sidibé narrative concerns this intertwining, between his photographic vision and the nationalistic milieu in which it unfolded. An early explication of the idea, in filmmaker and cultural theorist Manthia Diawara’s 2002 essay, “The Sixties in Bamako: Malick Sidibé and James Brown,” noted that his photographs “show exactly how the young people in Bamako had embraced rock and roll as a liberation movement, adopted the consumer habits of an international youth culture, and developed a rebellious attitude towards all forms of established authority.”

This intertwining of aesthetics and politics became clear only in retrospect. When Malians of that generation remember Sidibé, it is mainly through the lens of nostalgia. In a 2016 video interview in Paris, Diawara recalls himself as one of those young people who, in the late 1960s and early ’70s, formed clubs—“the rockers,” “soul brothers,” “sofas”—and took pictures posing with albums by Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, and Aretha Franklin. Sidibé, he said, “was the architect of my utopia.” “Today, I speak with nostalgia,” he added, “because he is my nostalgia.”

With my new bag, my ring and my bracelet, 1975/2001.

IT WAS NOT until 1995, when Sidibé was 60, that he had his first solo exhibition outside Africa, organized by the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain. From then on, rarely a year has passed without an exhibition of his work, and publications accompany most of those shows. This ongoing (even perpetual) commitment to his work owes likely, in part, to what Diawara articulated: There is no future to be glimpsed in these nostalgic images, but there is at least a hint of the uncomplicated past. In many West African countries, and in Mali for sure, the promise of freedom, cosmopolitanism, and rapid development as a modern state would soon be decimated by fratricidal politics and neocolonialism. Hence at their core, Sidibé’s images illustrate not just the buoyant movement and sound of those optimistic times but also evoke, to the multitude of his admirers, an African nation coming into its own.

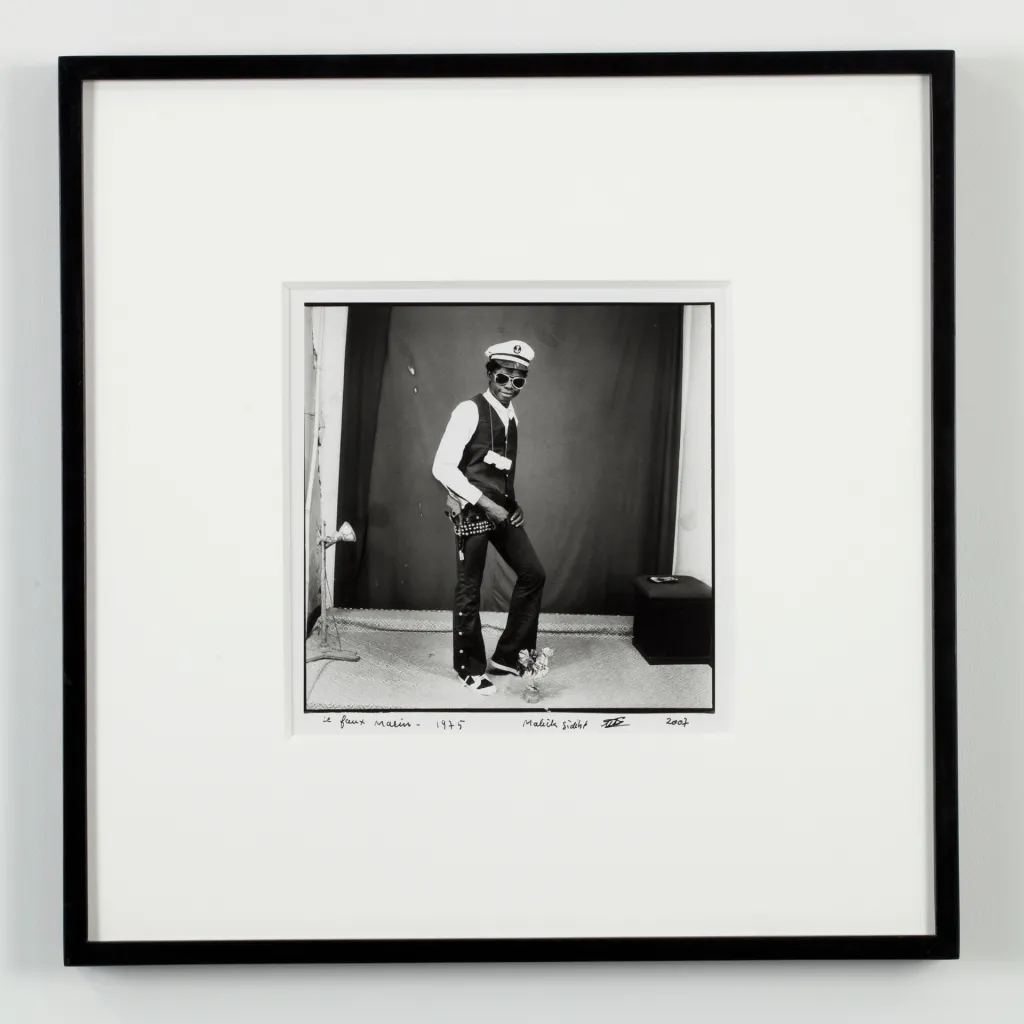

The newest Sidibé book is Painted Frames, published by the Marseille- and London-based studio Loose Joints. It accompanied a recent exhibition at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York, and spanned his most active period: the early ’60s through the late ’70s. A broad description of his oeuvre might begin with those photographs of frenetic, somewhat halcyon nighttime parties or visits to the banks of the Niger, followed by portraits of enthusiastic or demure posers he took in his studio, then a final series from the early 2000s, documenting back-facing subjects in his studio, mostly women.

Painted Frames collects photographs Sidibé curated from his entire oeuvre. Each photograph is encased in a glass painting of flowery forms, produced in the atelier of Checkna Touré, Sidibé’s longtime friend and collaborator. This iteration of their collaboration began after Jack Shainman and the late Claude Simard—cofounders of Jack Shainman Gallery—asked about a painted frame in the small studio one day. Previously, Sidibé and Touré had collaborated, but by the time of Shainman and Simard’s visit, the painter’s atelier had closed, as his clientele had gradually diminished. The dealers encouraged the artists to return to their collaboration, and to fulfill their request, Touré taught his sons the art of reverse-glass painting. The new book of these framed photographs achieves a remarkable feat of printerly quality, with nothing of the glare accompanying the transfer from glass to page. The book is, perhaps, indicative of Sidibé’s durability as a visual artist: His insights as a photographer were never reserved for the camera alone, but extended to a collaborative acumen, an affinity for sanguine exchanges between him and his sitters or friends.

Spread from Painted Frames.

Loose Joints

By the time Shainman and Simard saw that painted frame, the photographer was elderly, and visits to his studio starting in the mid-1990s, around the time French gallerist André Magnin visited Sidibé, tended to perpetuate veneration of his work by non-Malians. A recurring footnote in the contemporary history of African photography involves such eagerness on the part of Western art dealers. Most accounts of origins, retrievals, and discoveries point to chance encounters, as with the enthusiasm by which the careers of J.D. ’Okhai Ojeikere, Sanlé Sory, and Samuel Fosso were saved from international obscurity. I note this intending no disrespect to the productive and equitable relationship between those artists and their dealers, but to indicate how photographs like Sidibé’s travel in an oxymoron of benevolent capitalism.

These painted-frame photographs may nevertheless provide unique insight into what Sidibé himself intended as an overview of his decades of documenting Malian social life, as it is a rare selection that the artist curated himself. In fact, it includes surprising choices, most of them images taken outside his studio. One of them, for instance, is a photograph of possibly a wedding, in which neither bride nor groom looks into the camera, and only half the face of a man is seen. Or another of a woman flanked by two boys who both reach toward her with affection. And then the woman in a courtyard, regarding a young child with a smile, as he in turn considers the photographer with a timid glance. Those images project a feeling of intimacy too precious and unstaged for the studio to contain.

Each additional exhibition or publication that recirculates Sidibé’s photographs affords the opportunity to revisit his archive of Malian identity, and to consider why it matters today. In Painted Frames,his double role asan architect of utopia and purveyor of nostalgia is clearer in a material sense than in earlier retrospective projects. Sidibé’s nostalgia is doubled in his role as curator of his own archive, in Checkna Touré’s decision to return to the now obsolete art of reverse-glass painting, and in the key role his gallery played in kick-starting the project.

How was Sidibé, at the same time, an architect of utopia, looking forward and backward simultaneously? The metaphor is tangled. It includes a sense of how African photographers today might attempt to capture his energy by distilling his visual vocabulary down to the patterned fabrics and props in his studio, and to his evidently friendly relationships with those he pictured. It also points to the possibility of true globality, a world in which Bamako and Paris are equals in a cultural exchange. Yet, ultimately, we can simply celebrate Sidibé as a savvy master of functional art, much as Touré was. The least complicated reading of Painted Frames is probably the best: Sidibé chose the images based on what he wanted to pass on to his former clientele, and the rest of us are fortunate to catch a glimpse.