On a sweltering afternoon this past July, Miccosukee youth and cultural workers gathered at Panther Camp, the family grounds down the road from the fenced-off training airport where Florida officials had just erected the notorious migrant-detention facility that has been nicknamed Alligator Alcatraz. The action, coordinated in partnership with the collective Unidos Immokalee, was intentionally communal: hydration and medic teams were on standby, volunteers helped with safety and de-escalation, and young organisers distributed sunblock, insect repellent and art supplies for sign-making.

The organisers gathered on the shoulder of the Tamiami Trail, a thin, paved road that cuts through Big Cypress National Preserve, within view of Alligator Alcatraz, around 57 miles west of the Miami Beach Convention Center. On that day and in collective actions since, Miccosukee and Seminole artists, culture-bearers and youth organisers are using ceremony, performance and archiving to confront what they describe as a new chapter of colonial violence unfolding on ancestral lands.

“When we heard about the detention centre, people didn’t believe it could be real,” Kendal Osceola, a 26-year-old member of the Miccosukee Tribe who joined the tribe’s new archives department in autumn, tells The Art Newspaper. “The [site of Alligator Alcatraz] was always open—you could drive in, some of us swam in the man-made lakes. Suddenly there were trucks, fences. The land that protected us is being dug up for something backwards. Documenting how our community is standing up—elders and youth together—is now part of our responsibility.”

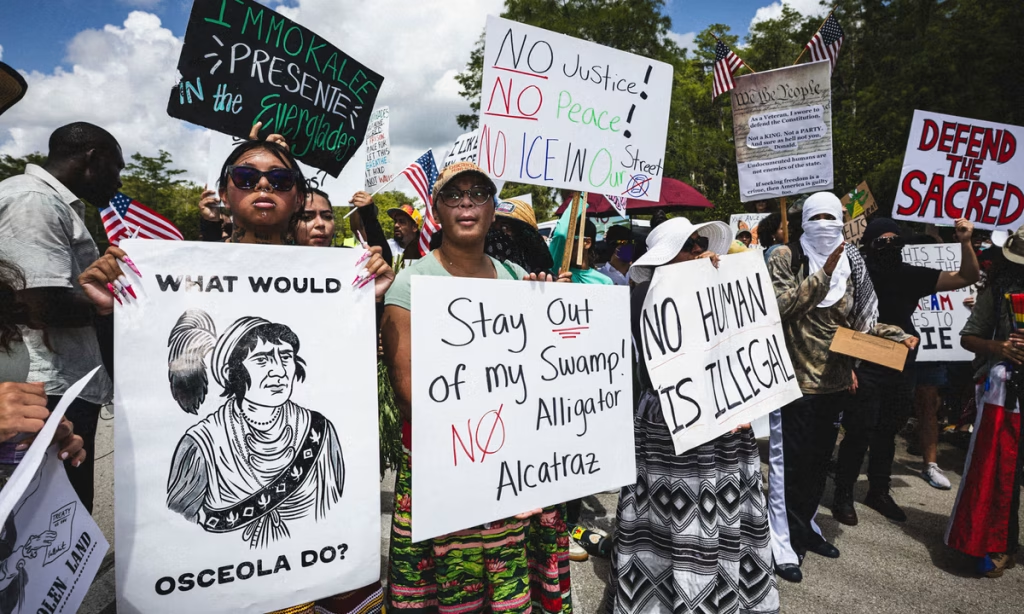

At the demonstration in July, patchwork skirts rustled as dancers moved to the beat of hand drums. Volunteers prepared food and distributed it freely. Hand-painted signs fluttered along the roadside. Voices from different communities were welcomed, as long as their messages were rooted in care. Even when a few outside agitators attempted to disrupt the gathering, the unity of the group held firm.

Then the skies opened. Rain poured over the marl and cypress, cooling the asphalt and easing the tension. Protesters crowded beneath tents, soaked through but buoyed by laughter, prayers and stories. The moment felt symbolic to those present: a reminder that resistance here is not only about shutting something down, but also about taking care of one another and believing that the Everglades—and its people—deserve a safer future.

Panther Clan’s youth leader Maeanna Osceola stepped forward to address the crowd and the cluster of cameras. (Osceola is a common surname in the Miccosukee community, and not all individuals who share it are related.) She reminded those gathered that this fight is happening in her own front yard. “I live 0.4 miles away from here, along with the rest of my family,” Maeanna said. “We recognise that our homeland is not only the foundation of our tribal sovereignty, but a vital, diverse ecosystem that many people and wildlife depend on for protection. We will not stand by and watch as history repeats itself.”

An accelerated opening

Florida officials announced plans for the detention facility at the remote Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport inside Big Cypress National Preserve in late June and moved quickly to open it on 3 July. The complex is the first federal immigration jail to be run by a state agency; Florida’s Division of Emergency Management operates it in partnership with the US Department of Homeland Security. For Indigenous artists and youth organisers, the facility is a direct threat to ecology, sovereignty and community safety—and a reminder that the Everglades remain a battleground.

Community opposition to the facility has gained traction in court. In August, a federal judge temporarily halted new construction amid an environmental lawsuit, and subsequently ordered that the facility be closed pending a full review. In early September, however, a divided appeals panel stayed the shutdown order, allowing operations to continue while litigation proceeds—leaving the site open as the case winds its way through appellate court. Aspects of the appeal were paused during the federal government shutdown, from 1 October until 12 November, prolonging uncertainty for detainees and local communities.

For many in the South Florida arts community, the fight over Alligator Alcatraz is inseparable from the history of the Everglades. The detention complex sits at the one-time epicentre of the so-called Everglades Jetport scheme, a 1960s plan to build the world’s largest airport. Miccosukee leaders and environmentalists helped stop construction of the project in 1970, and in 1974 federal officials created the Big Cypress National Preserve. That episode is a touchstone for today’s organisers—proof that sustained, culturally rooted opposition can halt megaprojects in fragile environments.

A protester at the entrance to Alligator Alcatraz; legal action to close down the immigration-detention centre is ongoing, but in the meantime, it remains operational, sparking controversy and protests

UPI/Alamy

Cultural practice as resistance

The cultural response to Alligator Alcatraz this past summer unfolded in waves. After the detention centre opened, a coalition of Indigenous youth and allies organised actions that connected environmental stewardship and immigrant rights.

“We kept each other safe—there was singing, dancing, people weeping,” Dakota Osceola says. “We’re not going to pray away a detention centre, but ceremony helps us cope and stay together.”

Dakota, who supports their family through traditional Miccosukee beadwork—a practice they learned as a child and which, they say, saved their life and kept them sober—frames art as both mutual aid and movement infrastructure. In collaboration with Unidos Immokalee and the group Unconquered Coalition, they have helped organise food distribution for families of detainees.

“Florida is so spread out,” Dakota says. “Not everyone can show up to protest, but they can shop from a wish list or help us pay rent for families. Art built the relationships that make that possible. It brings people together; it’s a coping mechanism—and it’s how we organise.”

During a prayer action on 26 October, the Miccosukee elder and organiser Betty Osceola addressed a circle of supporters, speaking about the role of creative and spiritual expression in sustaining collective resistance.

“You have music for change, artists for change,” Betty said. “Bringing music out here and uplifting, because the environment needs something to uplift it, because right now it has a lot of sadness and depression and anger going on a mile from here.”

Within Miccosukee governance, the archives department where Kendal works is barely a year old—formed, they say, to ensure the tribe authors its own history rather than being “lumped together” or misrepresented by outside institutions. In preparation for the 26 October action, the staff read guidelines on documenting demonstrations ethically, then fanned out to collect signs, record oral histories and, where offered, accept anonymous donations of materials.

“This is a historic moment,” Kendal says. “We want to preserve it thoroughly—but safety is our priority. People decide what to share and how to be named, if at all.” For Kendal, who has worked as a guide at the nearby Miccosukee Indian Village museum, the stakes are cultural and spiritual. Alligator Alcatraz stands near camps associated with Panther Clan—keepers and caretakers of medicinal and spiritual knowledge.

“In the morning, we’ll be able to hear the trucks,” says Gunny, a Miccosukee Bird Clan member and organiser who grew up on a family camp located minutes from the detention centre site. “When we light the fire at night, we’ll be able to see their lights instead of just our firelight.”

Gunny adds: “As Indigenous people, art is part of who we are—it’s our songs, it’s our dance, it’s our traditional arts which carry our history.”

Activists’ creative tactics in response to Alligator Alcatraz are varied and have included land-based rituals at the preserve’s edge, processions that blend patchwork regalia and screen-printed banners, and careful visual documentation for the archive. The emerging collection of posters, songs and testimony joins a long continuum of Seminole and Miccosukee cultural production that often blurs art and life. It is also a practical organising tool. Images and reels circulate among farmworker networks and mutual-aid groups, helping neighbours warn one another of police and immigration activity.

If the Jetport fight is the movement’s historical North Star, the Everglades’ layered sovereignties are its contemporary map. The Big Cypress National Preserve was created in part to protect water flow into Everglades National Park; its management requires balancing ecological restoration with public access and, critically, respect for tribal rights and use. That complexity has become acute at the detention centre, where questions of jurisdiction—federal, state and tribal—now intersect with immigration enforcement.

For Miami Art Week’s global audience, the scene in Big Cypress is a reminder that the Everglades is a living, Indigenous homeland where ecology, culture and resistance are braided together. “Remember our past to provide our youth a better future,” Kendal says. “That’s the work.”

Kendal believes the archive can keep these layers legible. “We’re starting from zero in many ways—many records have never been processed,” they say. “But the mission is clear: our community first. In the future, some materials may be shareable publicly, others will remain within the tribe. The point is that we speak for ourselves.”