“I never saw such poverty as I saw in Rousseau’s studio,” recalled the artist Max Weber, one of the first patrons of the self-taught painter Henri Rousseau (1844-1910). Having retired early from a job in the toll booths of Paris to pursue his dream of being an artist, Rousseau faced constant money struggles. In 1907, he was embroiled in bank fraud and put on trial. Defending him as a simple soul who was duped, Rousseau’s lawyer deployed his untutored paintings as proof of his “naivety”.

This myth of unworldly innocence was spread after his death by the artists, critics, dealers and collectors who championed the amateur they nicknamed “Le Douanier” (the customs officer). His reputation and market were booming by 1923, when the US collector Albert C. Barnes paid the dealer Paul Guillaume 45,000 francs (plus commission) for his first Rousseau—on a par with prime works by Henri Matisse or Pablo Picasso. Only 15 years earlier, a young Picasso had rescued a discarded Rousseau canvas from a junk shop for five francs.

Barnes and Guillaume formed the two largest collections of Rousseau’s work, with 18 and 11 paintings respectively. Many of these will be reunited for the first time in over a century this month, as part of Henri Rousseau: A Painter’s Secrets (19 October-22 February) at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. It travels next year to the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, home to the Guillaume collection.

‘Incredible discoveries’

“Uniting the two collections was the perfect foundation for the show,” says Nancy Ireson, the deputy director for collections and exhibitions at the Barnes Foundation and the co-curator of the exhibition with Christopher Green, professor emeritus at London’s Courtauld Institute of Art. The project was made possible by the foundation’s 2023 court case, which permitted paintings to be lent outside the fixed ensembles conceived by Barnes himself. Ireson describes “an amazing opportunity to create new pairings” that help to bust some of the old myths around Rousseau.

While Green notes that “a lot of Rousseau’s secrets will never be known”, new conservation research on the Barnes paintings has revealed “some incredible discoveries”. Traces of myriad revisions suggest he tactically adapted his compositions to attract clients. Frugal by necessity, he reused some canvases by completely overpainting them. Rousseau “had real ambitions to earn a living from his work”, Green says. “Ultimately, he failed. But he made extraordinary work while trying to do so.”

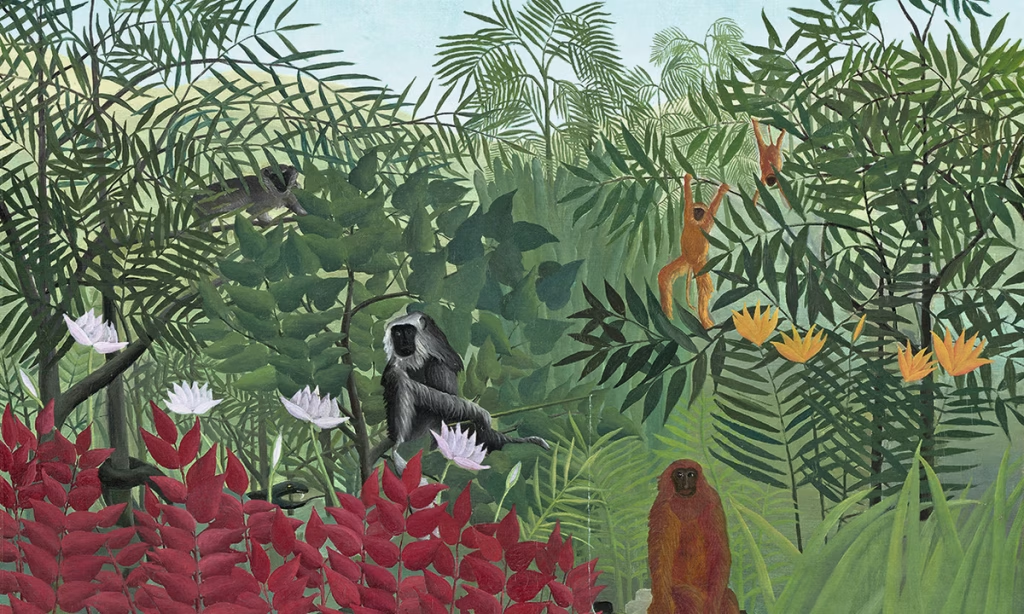

The show will focus on the artist’s search for an audience while embracing different themes, from the political allegory of War (around 1894) to his popular scenes of wild beasts in lush jungles. These fantastical inventions—inspired by illustrated magazines and sketches at the Paris botanic garden—were a knowing “attempt to make a spectacle” at the city’s open-submission salons, Ireson says. It took years before mockery gave way to genuine acclaim, but Rousseau collected positive and negative press clippings alike. “He understood the power of recognition,” Ireson says.

Other sections will capture the “petit bourgeois” suburban milieu in which Rousseau eked out a trade before his avant-garde admirers came knocking. He produced portraits and landscapes for families and business owners in his neighbourhood, sold at modest prices or bartered for professional services.

The curators’ goal to “bring out the nuance” of Rousseau’s workaday reality is “not to deny the mystique”, Ireson says. “We want to celebrate the fact that in some ways he remains an enigma, but we’re offering clues as to how visitors might interpret him.”

The closing section, “An Enigma”, will feature three large-scale paintings: The Sleeping Gypsy (1897), Unpleasant Surprise (1899-1901) and The Snake Charmer (1907). Hovering between calm and danger, they remain powerfully “open to interpretation”, Green says. They also embody a tipping point in Rousseau’s fortunes, from pauper to visionary Modern artist. Each entered an important collection after his death—The Snake Charmer going to the Louvre, where he once copied the great masters. “In a sense, they establish Rousseau’s legacy… which he would’ve been delighted with, but couldn’t have foreseen during his lifetime,” Ireson says.

• Henri Rousseau: A Painter’s Secrets, Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, 19 October-22 February 2026; Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris, 24 March-20 July 2026