Born in Wakefield, Yorkshire in 1903 and working until her death in 1975 in St Ives, Cornwall, Barbara Hepworth lived through a time of astonishing technological and social change. She had a broad range of interests, from politics to music, poetry, science and spirituality—and a life-long engagement with landscape—which she brought into her work, alongside influences from her personal life. She believed passionately in the role of art in society, both in terms of public sculpture, and the power of art to reflect and influence our relationships with each other, and with the world in which we live.

Here we round up 10 works by the famed sculptor, on show at a range of museums and galleries around the UK.

1. Infant, 1929

Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden, Cornwall

Barbara Hepworth, Infant (1929)

Barbara Hepworth © Bowness. Photo: © Ginny Sturdy/Shutterstock

Hepworth was a proponent of direct carving, the practice of carving directly into the wood or stone. She favoured hard woods, like the Burmese wood used for Infant, which was very difficult to carve. Reviews of her early exhibitions in the 1920s particularly praise her technical ability, and the sympathetic dialogue between organic material and the forms she created. Infant was made after the birth of her first son, Paul Skeaping, which she described as “a wonderfully happy time … with him in his cot, or on a rug at my feet, my carving developed and strengthened”.

2. Three Forms, 1935

Tate Britain, London

Barbara Hepworth, Three Forms (1935)

Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

Hepworth’s early sculptures were representational carvings of figures or animals, though she noted in 1930 that there are, “degrees between pure representation and the abstract”. After the birth of her triplets in 1934, she wrote: “the work was more formal and all traces of naturalism had disappeared…although the only fresh influence had been the arrival of the children.” Pure white, multi-part sculptures like Three Forms show Hepworth’s new focus on “the relationships in space, in size and texture and weight, as well as in the tensions between the forms” with which she hoped “to discover some absolute essence in sculptural terms giving the quality of human relationships”.

3. Pierced Hemisphere, 1937

The Hepworth Wakefield

Barbara Hepworth, Pierced Hemisphere I (1937)

Marble Barbara Hepworth © Bowness. Photo: Jerry Hardman-Jones

Hepworth pierced through the sculptural form in a non-representational way as early as 1932, and this would become an iconic aspect of her sculpture. She was interested in the way that pierced forms like this one entice the viewer to move around the sculpture, incorporating both light and space as sculptural materials alongside wood and stone. By the time Pierced Hemisphere was made, Hepworth had become part of an international avant-garde based in London, and contributed to the 1937 publication Circle: An International Survey of Constructive Art, which proposed abstraction as a universal language that could unite people in the face of rising Fascism.

4. Sculpture with Colour (Oval Form) Pale Blue and Red, 1943

The Hepworth Wakefield

Sculpture with Colour (Oval Form) Pale Blue and Red (1943)

Barbara Hepworth © Bowness. Photo: Betty Saunders

In 1939, on the brink of the Second World War, Hepworth moved with her young family to the relative safety of Cornwall. It was not until 1942 that she had a house large enough to have a small studio, and was subsequently granted a special permit to obtain wood. She began to work with colour and strings in response to her new environment. She recalled: “The colour in the concavities plunged me into the depth of water, caves, or shadows deeper than the carved concavities themselves. The strings were the tension I felt between myself and the sea, the wind or the hills.” This is one of the earliest wood carvings to incorporate colour and strings, and the only of Hepworth’s sculptures to include multi-coloured strings.

5. Pelagos, 1946

Tate Britain

Barbara Hepworth, Pelagos (1946)

Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

The landscape of Cornwall would be an important source of inspiration for Hepworth for the rest of her life, but rather than simply depicting it, she sought to embody the feeling of being within the environment through her sculptural forms. This is perhaps typified in Pelagos (1946), which Hepworth chose as the cover image for the catalogue of her 1968 Tate retrospective. Its title means “sea” in Greek, and it relates to the view from Hepworth’s studio, “looking straight towards the horizon of the sea and enfolded (but with always the escape for the eye straight out to the Atlantic) by the arms of the land to the left and the right of me”.

6. Concourse (2), 1948

Hunterian Museum, London

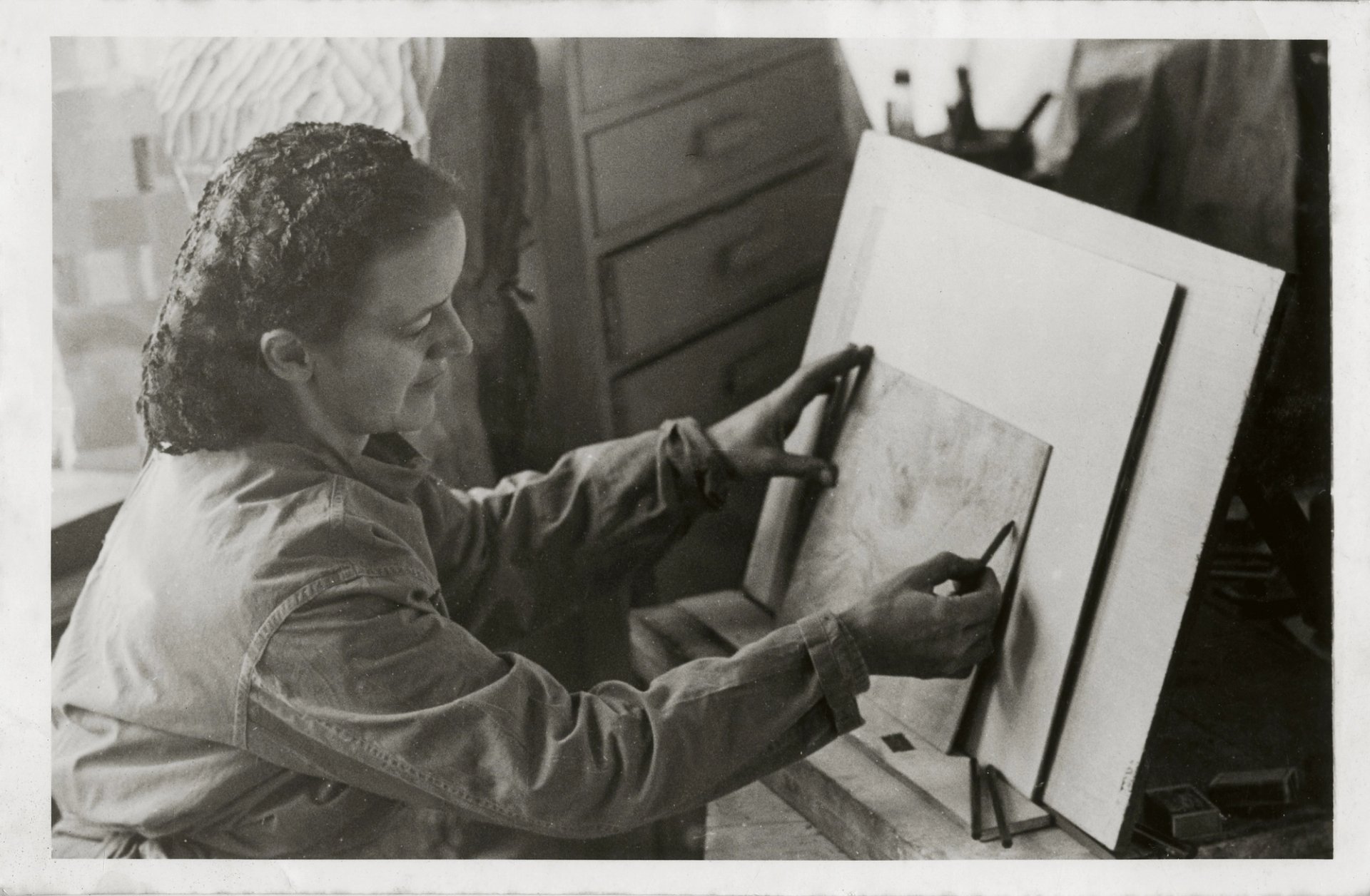

Barbara Hepworth at work on Quartet I (Arthroplasty), another operating theatre drawing, Cornwall, 1948

© Bowness

During the war, one of Hepworth’s daughters became ill and required a series of operations. The surgeon invited Hepworth to witness an operation in 1947, and her subsequent paintings and drawings made over the next few years— known as her Hospital Drawings and including Concourse (2)—marked her return to figurative art. She wrote in 1949: “working realistically replenishes one’s love for life, humanity and the earth. Working abstractly seems to release one’s personality and sharpen the perceptions… The two ways of working flow into each without effort.” The Hospital Drawings capture what Hepworth described as the “extraordinary beauty of purpose and co-ordination between human beings all dedicated to the saving of life”.

7. Contrapuntal Forms, 1950-51

Public display, Harlow

Barbara Hepworth, Contrapuntal Forms (1951)

Barbara Hepworth © Bowness. Photo: courtesy of the Harlow Art Trust

This was Hepworth’s first major public sculpture, commissioned for the Festival of Britain, held in 1951 to celebrate Britain’s post-war achievements in technology, industrial design, architecture and the arts. Hepworth had begun titling her works after musical elements in the late 1940s, and was particularly inspired by her friendship with composer Priaulx Rainier, who she met in 1949. Rainier gave her a copy of Igor Stravinsky’s book, The Poetics of Music, which Hepworth felt highlighted great parallels between the construction of musical and sculptural form. Contrapuntal is a musical term, meaning that each element is the counterpoint to the other.

8. Curved Form (Delphi), 1955

Ulster Museum

Barbara Hepworth, Curved Form (Delphi), 1955

Barbara Hepworth © Bowness, Ulster Museum Collection

In 1953 Hepworth’s son Paul died in an aircraft accident. The following year, a friend took her to Greece in an attempt lift her grief. The landscape deeply moved Hepworth, and of Delphi she wrote: “On a fair and glorious morning I managed to escape some 400 people and ascend the hill alone and in silence […] standing alone in the stadium, alone below Olympus, I felt at ease both physically and spiritually”. On her return, Curved Form (Delphi) became one of the first of several sculptures carved from huge logs of Guarea wood. The strings continue to express Hepworth’s relationship with landscape, while also evoking the lyre of Apollo, god of healing, truth and light, whose temple is at Delphi.

9. Single Form, 1961-4

United Nations headquarters, New York

Barbara Hepworth, Single Form, 1961-4

Single Form at the UN Secretariat; 11 June 1964. © Bowness

Hepworth remained politically engaged after the war. In 1961, she co-authored a statement opposing nuclear weapons, writing: “Culture means the affirmation of life…they are the negation of life.” Dag Hammarskjöld, the secretary general of the United Nations (UN), had become a friend, and they met in London when he gave an address on the UN’s diplomatic role in achieving global nuclear disarmament. In September 1961 Hammarskjöld was killed in a plane crash, and Hepworth was commissioned to make a monumental sculpture for the UN headquarters in New York in his memory. At its unveiling, Hepworth said: “The United Nations is our conscience. If it succeeds it is our success. If it fails it is our failure…I have tried to perfect a symbol…of both continuity and solidarity for the future.”

10. Four-Square (Walk Through), 1966

Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden, Cornwall

Barbara Hepworth, Four-Square (Walk Through), 1966

Barbara Hepworth © Bowness. Photo: Horst Friedrichs / Alamy

Hepworth made nearly as many sculptures in the 1960s as in her career up to this point, taking on a second studio to allow for her monumental commissions and invigorated output. In 1973 she asserted: “One is physically involved and this is sculpture”, emphasising the importance of bodily engagement, which perhaps reaches its apotheosis in Four-Square (Walk Through), where the viewer can enter the sculpture. She wrote in 1966: “so much depends, in sculpture, on what one wants to see through a hole! Maybe, in a big work I want to see the sun or moon…It is the physical sensation of piercing & sight which I want. I like to be free & at the moment I have 20 ‘collared doves’ flying through 4 giant holes in my ‘walk through’ sculpture. I just love it.”