Art

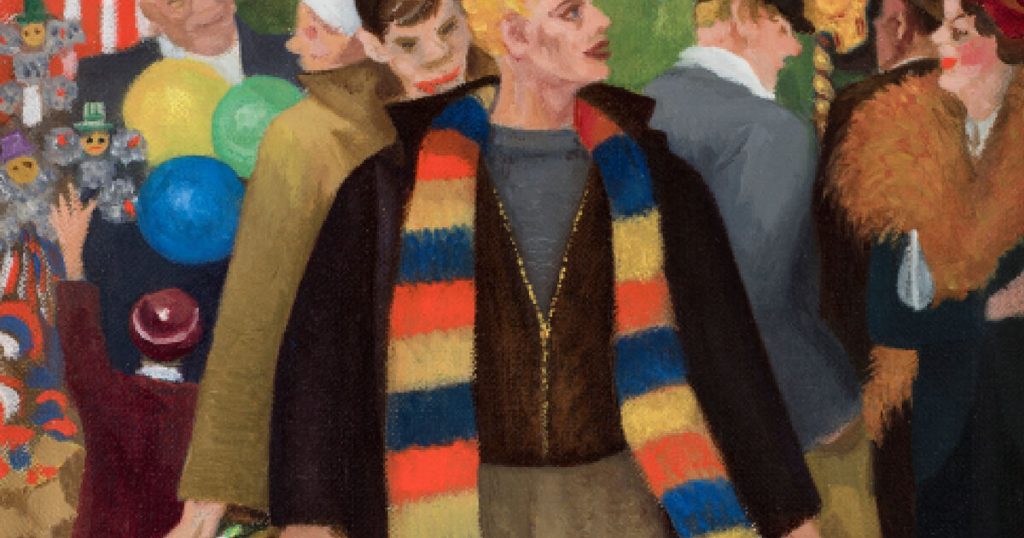

Gluck, Bank Holiday Monday, ca. 1937. Courtesy of The Fine Art Society Ltd © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025. Courtesy of Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen.

Marie Laurencin, Danseuses Espagnoles, 1921. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025. Courtesy of Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen.

In Bank Holiday Monday (1937), queer desire unravels in plain sight within a crowded carnival ground. The kaleidoscopic painting, by British nonbinary artist Gluck, centers on two fashionable, androgynous figures: One, with close-cropped brown hair (like the artist’s own), looms over her peroxide-blond partner’s shoulder, seductive and sinister. The two are physically present in the scene, standing in the trash-strewn grass, but seem to exist in a bubble—speaking a language of forbidden yearning and coded self-expression.

These are the visual cues on view throughout “Queer Modernism: 1900 to 1950,” a comprehensive new exhibition of over 130 works by 34 artists at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen’s K20 space in Düsseldorf, Germany. Rewriting a half-century of Western art history through a queer lens is noble—and necessary. Although modernism was defined by its rejection of traditional values and embrace of experimentation, it was a cadre of straight, white, male artists like Pablo Picasso and Vincent van Gogh who came to dominate the canon. The new exhibition reframes modernism as a movement shaped by queerness, not merely touched by it.

Ludwig von Hofmann, Die Quelle, 1913. Photo by Stephan Bösch. Courtesy of Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen.

The vibrancy of Bank Holiday Monday helps to define the show. It’s also a moment of new visibility for the mononymic British painter who dropped their given name, Hannah Gluckstein, in 1918, and became one of England’s most prominent gender-defying artists. This inclusion reflects a broader trend across the art world, where galleries and institutions have sought to reevaluate historical movements in recent years to recognize the impact of marginalized artists.

Of the 331 participating artists and collectives in the main exhibition of the 2024 Venice Biennale, for instance, there were dozens for whom queerness was central to their practice. The art market has also begun to catch up: early queer icon Rosa Bonheur’s Emigration de Bisons (Amérique) (1897) sold for $773,500 in 2019, while other artists represented in the exhibition, including Richmond Barthé, Leonor Fini, Beauford Delaney, and Paul Cadmus, have also sold works in the upper six figures or higher at auction in recent years.

Installation view of “Queere Moderne. 1900 bis 1950,” Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, 2025, Photo by Achim Kukulies. Courtesy of Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen.

There is a growing appetite for this long-overlooked history, and “Queer Modernism” makes a persuasive case for rewriting it. “It cannot only be about integrating seemingly marginalized artists into the center of the discourse on modernism,” said curator Anke Kempkes. “An exhibition like this is changing our perspective on the history of modernism, which has usually been told linearly. We see now that the whole picture is so much broader and more complex and complicated.”

The exhibition contains work from across five decades, when queer artists turned to the very materials of modernism—abstraction, fragmentation, and reduction—to encode desire and difference in plain sight. At the very start of the show is Untitled (Seated Man, Multiple Images) (1927), by Russian Surrealist painter Pavel Tchelitchew, whose partner, Charles Henri Ford, co-wrote The Young and Evil, a salacious (and quickly banned) novel about New York’s gay underground scene in the 1930s.

Nils Dardel, Visit how excentrisk dam (Visit to an Eccentric Lady), 1921. Courtesy of Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen.

Anton Prinner, Double personnage, 1937. Courtesy of Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen.

The moody, cerebral portrait shows a lone figure in a shabby gray suit, his face split into three overlapping expressions as his limbs abnormally intertwine. The faces suggest layers of identity, while the tangle of limbs can be read as either a lover’s embrace or a desperate struggle to reconcile a fractured identity.

“Tchelitchew criticized Picasso’s analytical Cubism and sterile modernism for being lifeless and for not being able to capture life, sexuality, desire, and physical forms of embodiment,” said Kempkes. Elsewhere in the show, works explore the expression of queer identities in the early 20th century, when homosexuality was still criminalized for men and socially taboo for women across Europe and the U.S. In Glyn Warren Philpot’s Penelope (1923)—a standout painting, which sold for over £337,000 at auction in 2021—queer desire is camouflaged in Greek mythological imagery. Though the title refers to Odysseus’s wife from Homer’s Odyssey, Penelope almost recedes into the canvas as she’s depicted on a chair, weaving a shroud.

Installation view of “Queere Moderne. 1900 bis 1950,” Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, 2025, Photo by Achim Kukulies. Courtesy of Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen.

Instead, Philpot focuses on the three male suitors surrounding her—particularly one whose barely covered backside dominates the foreground, with his groin just inches from her upturned gaze. The work simmers with repressed sexuality, reflecting the artist’s own conflict as both a gay man and a practicing Roman Catholic. By rendering homoeroticism through gazes and the male form, Philpot navigated the tension between desire and the moral codes of this era.

Greek mythology as a lens for queerness recurs most vividly in the story of Narcissus, the handsome young man who falls in love with his own reflection in a pool of water. This became particularly salient due to Freud’s dominating influence on 20th-century thought. The psychoanalyst famously pathologized homosexuality as a kind of “misdirected love of the self.” But artists of the time took that diagnosis and flipped it, navigating their same-sex desires not through shame, but reclamation.

Nils Dardel, Den döende dandyn (The Dying Dandy), 1918. Courtesy of Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen.

This reversal is made explicit in a work by Harlem Renaissance figurehead Richmond Barthé. Barthé’s Black Narcissus (1929), on view in the show, features a young nude figure in bronze, one hand on his hip, as another holds a small mirror which he confidently gazes down at. Elsewhere, Swedish painter Nils Dardel’s The Dying Dandy (1918) depicts a young man lying weakly against a pillow, one hand clutching his heart while the other holds a mirror to himself. Whereas Barthé’s muted bronze depicts a lone man, Dardel has painted four colorful mourners surrounding the central dandy. Viewed through the lens of the dominant Freudian analysis, the tableau feels almost biting in its sarcasm: Here lies the extravagant, dying man, surrounded by love but in a world of his own as he passes away from an excess of vanity.

Though Dardel’s theatrical, colorful satire offers a moment of levity, it can also be read as a melancholic reflection on the pressure of trying to express yourself. This struggle for acknowledgment still plays out today. Queer modernists may finally be getting their flowers and some market recognition, yet their legacies remain vulnerable to misrepresentation. “There were two instances where the estate side or the holders of an archive, not necessarily legal heirs, were trying to influence the interpretation of the queer legacy of the artist in a way that would make it less visible or less explicit,” Kempkes shared. It’s a reminder that art doesn’t exist in a vacuum; what makes it onto museum walls must still navigate real-world prejudice.

In the exhibition’s “Epilogue” section, Sonja Sekula’s Silence (1951) provides a quietly powerful close. Dedicated to her friend John Cage, the painting was created during the Lavender Scare, when paranoia about homosexuality in the U.S. government fueled widespread repression. Beside it, a wall text quotes Cage: “I have nothing to say, and I am saying it.” The pairing underscores a larger truth: queerness has always existed in tandem with suppression. For Kempkes, today’s resurgent conservatism gives the exhibition added urgency: “In a time when queer life is increasingly threatened, it is particularly important to make visible the rich and far-reaching history of queer culture.”

CE

Chris Erik Thomas

Chris Erik Thomas is a Berlin-based journalist and editor covering art, fashion, and culture. He previously worked as the digital editor at Art Düsseldorf for two editions of the fair, and his writing has appeared in Fantastic Man, ARTnews, Highsnobiety, The Art Newspaper, and numerous other publications. His newsletter, Public Service, is a catalog of fixations and essays.