Since his early death at the age of 27, the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat’s reputation—and prices for his work—have continued to grow.

The author of Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Making of an Icon, Doug Woodham, knows the art market well: a former president of the Americas for Christie’s auction house, he is now the managing partner of the New York-based firm Art Fiduciary Advisors. While Woodham and Basquiat had wildly different trajectories, in the introduction Woodham claims some affinity with him through their middle-class origins, churchy background and similar age. But the real reason for the book, Woodham writes, is his “admiration for the artist’s insatiable curiosity, self-directed ambition and determination to carve out a place for himself in the world”.

The book falls into two halves. The first is a straightforward biography: an intellectually gifted child, born in Brooklyn in 1960 to Matilde, a loving and nurturing woman of Puerto-Rican heritage, and a Haitian-born father. This happy childhood was shattered by his mother’s descent into mental illness, his near-fatal accident and the breakdown of his parents’ marriage. Shuttled between schools in Puerto Rico and New York, Basquiat began playing truant and experimented with drugs, sex and alcohol, before starting the street art project tagged “SAMO©” alongside Al Diaz.

Shooting star

Despite this down-and-out period in his early life, Basquiat’s talent was soon recognised—as a dancer, musician and artist—and by 1980 he was mentioned in Art in America magazine. Three years later, aged just 22, he was one of the youngest artists at the Whitney Biennial; in the same year he became friends with his hero, Andy Warhol, and moved into a loft owned by him. From there his success grew, peaking in 1984-86. But his heroin use increased, fuelled by the money he was earning as an artist. In 1988 he died of an overdose.

Information about Basquiat’s life is readily available, and there are several biographies already written. What adds to our knowledge is the second half of this book, in which the author analyses how this “radiant child” achieved such success so early. It also examines the influence of Basquiat’s father, Gerard, and his determination to frame the narrative about his son’s life, sexuality and drug use. As a result, the book contains no images of Basquiat’s work: “Much of the existing literature has neglected critical aspects of his character and life experiences… The Basquiat estate refused permission to include images of his artwork in this book because these and other issues are openly addressed,” writes Woodham.

The book details the myriad problems posed by evaluating the amount of tax payable on Basquiat’s estate, as well as the bitter legal battle with Vrej Baghoomian, who had represented the artist before his death and claimed exclusive rights to the sale of all the works in the estate. (Baghoomian finally lost; he is now deceased). Although Woodham is careful not to criticise Gerard—also no longer alive—he comes across here as manipulative and litigious. After a strained relationship with his son, on Basquiat’s death Gerard fiercely guarded the artist’s reputation and legacy, but also profited enormously from it.

Collectors and tastemakers

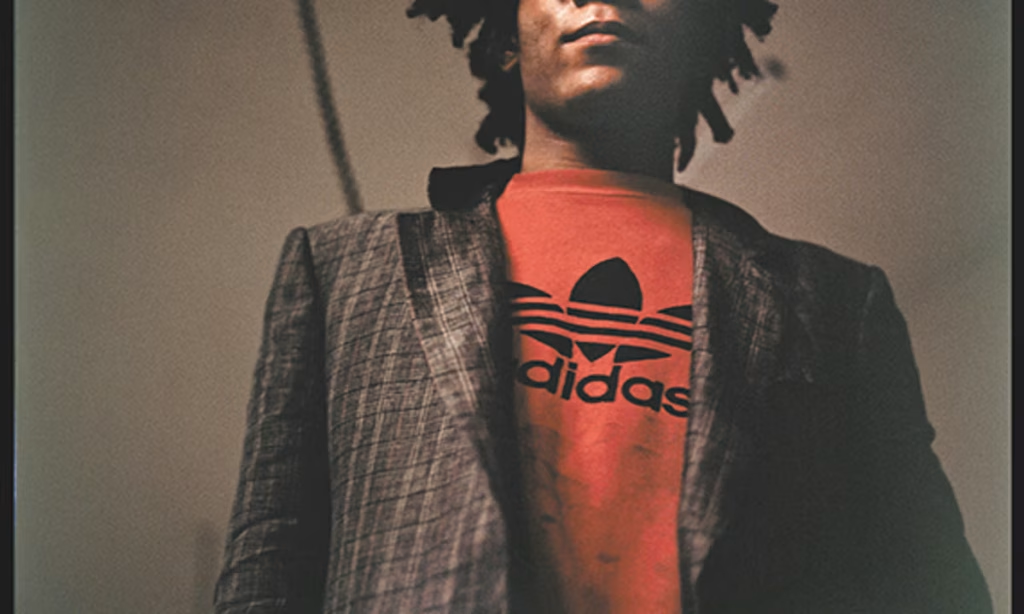

Woodham emphasises the importance to Basquiat’s early success of collectors such as Peter Brant and José Mugrabi, as well as tastemakers in the rock star world, notably Adam Clayton of U2. The artist’s counterculture behaviour and even his Blackness were an important attraction for buyers. As Woodham writes: “Into the [1980s boom] for expressive art stepped the highly expressive Basquiat—a tall, handsome, bisexual, self-taught Black man who was ambitious, well-read and unapologetically provocative. Sexy and cool, he challenged and charmed those around him, making him an ideal figure for the 1980s art boom.”

His tragically early death only fuelled interest in his work, and such was the increase in prices over the following decades that commercial branding and collaborations became an important source of income for the estate, as well as contributing to the artist’s renown.

His reputation, once dismissed as a passing fad, has been strongly revalued. Basquiat is now an icon, as stated in the subtitle of this book, not only for collectors from his peer group, but for newer generations. In 2017 Yusaku Maezawa, an eccentric Japanese internet billionaire, spent $110.5m on Untitled (1982), a painting of a skull on a cerulean-blue background, sealing Basquiat’s reputation as one of the highest priced contemporary painters, as well as one whose work has transcended his own lifetime.

• Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Making of an Icon, by Doug Woodham. Published 14 October by Thames & Hudson, 296pp, 60 colour illustrations, $34.95/£30