Art

Aina Onabolu, Portrait of an African Man 1955. © Aina Onabolu. Courtesy of Tate Modern.

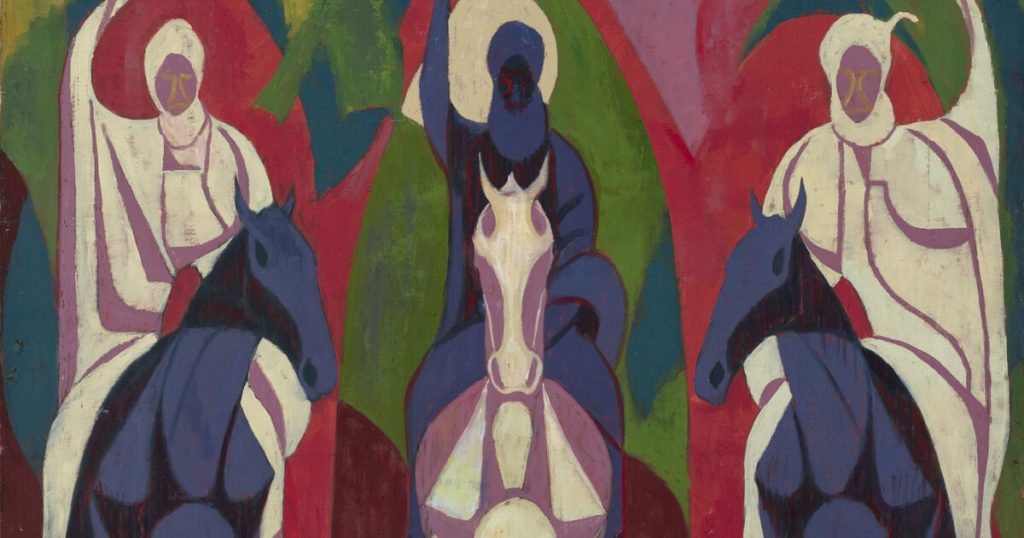

Jimo Akolo Fulani Horsemen 1962 © Reserved. Courtesy Bristol Museum and Art Gallery

In his 1920 book, A Short Discourse on Art, Nigerian artist Aina Onabolu wrote of West African art, “Our drawings are still crude; destitute of Art and Science.” In keeping with this belief, Onabolu rejected Nigeria’s art conventions in his figurative portraiture. Instead, he replicated the British style but took Nigerians as his subject matter.

In the 1920s, he petitioned the British colonial powers to introduce Western art instruction to the Nigerian curriculum. It’s ironic, then, that this directly led to the art movement now known as Nigerian Modernism, a movement that, in many ways, was defined by the rejection of colonial ideals.

Fast forward to October 1, 1960, when Nigeria gained independence from Britain. At this moment, the whole country grappled with what its national identity meant, given that it was made up of over 100 disparate ethnic groups. For artists building on the modernist movements sweeping the globe, it was a time to define Nigeria for themselves. In works from this period, they depicted colorful and quotidian contemporary Nigerian life on canvas rather than just the landscapes the British preferred, incorporating traditional mediums like metalwork and beading into their practices.

Obiora Udechukwu, Our Journey 1993 © Obiora Udechukwu. Courtesy of Tate Modern.

Today, Nigerian Modernism is finally gaining international recognition with a major new exhibition on the movement opening at Tate Modern on October 8, 2025. “Nigerian Modernism,” curated by Osei Bonsu and Bilal Akkouche, will explore the evolution and shifting trajectories of the art movement. An exhibition of this breadth and depth provides an opportunity for international audiences outside of West Africa to learn about one of Nigeria’s defining art movements.

The history of Nigerian Modernism

Nigerian Modernism doesn’t have a clear beginning date, though it is generally understood to apply to works made between the 1940s and the early ’90s. A striking combination of factors were at play: Nigerian artists working during this period experienced the growing anti-colonial sentiment in the country, as well as the spread of Western art instruction. They were united by attitude: a desire to define themselves on their own terms.

Akkouche conceives of Nigerian Modernism as “a continuum of artistic responses that evolved across the 20th century.” Onabolu, who returned to Nigeria in the 1920s after studying art in Europe, represents the beginning of this “continuum.” He encouraged the adoption of Western techniques and ideals in Nigeria and even taught them himself. His portraits present a straightforward adoption of this aesthetic: painting Nigerians in the style of British painters.

Clara Etso Ugbodaga-Ngu, Elemu Yoruba Palm Wine Seller, 1963. © Clara Etso Ugbodaga-Ngu. Courtesy of Tate Modern.

Uzo Egonu, Stateless People an artist with beret 1981. © The estate of Uzo Egonu. Courtesy of Tate Modern.

By the 1940s, the first set of formally educated Nigerian artists emerged, after training with Western art instructors who had arrived in the country. For example, Ulli Beier, a German writer and scholar, and his wife, the Austrian artist Susanne Wenger, moved to Nigeria in 1950. Beier would go on to found the Mbari Club in Ibadan and run artist workshops in Osogbo, both of which acted as magnets for many of the artists who would become significant contributors to Nigerian Modernism. Another key supporter of Nigerian art was Kenneth Murray, an archeologist, artist, and curator. He went on to train Akinola Lasekan, who painted Yoruba legends and royalty on paper and canvas rather than on the traditional wood.

Lasekan went on to share his knowledge of Western art techniques with Nigerian students in government colleges. However, he remained strongly influenced by indigenous traditions. In the mid-1940s, Lasekan became Nigeria’s first political cartoonist, using his art to promote anti-colonial sentiments and came to embody the incipient Nigerian national spirit.

In 1958, a growing spirit of national independence led to the founding of the Zaria Art Society. This group of university students included many painters who would go on to become major figures in the Nigerian Modernist movement, such as Uche Okeke, Demas Nwoko, Yusuf Grillo, Bruce Onobrakpeya, and Simon Okeke. These artists rejected outright the Western bent of their lectures and insisted on incorporating indigenous work. They fused Igbo traditional design, such as curved uli forms, with experiments in abstraction and Surrealism. This was “art as nation-building, a refusal of provincialism, and proof that modernism could be made in Nigeria, not borrowed,” said Aindrea Emelife, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Museum of West African Art in Benin City, Nigeria.

J.D. Okhai Ojeikere, Untitled (Mkpuk Eba), 1974, printed 2012. © reserved. Courtesy of Tate Modern.

When Nigeria gained its independence, this national spirit came to a fever pitch. Artists all over the country felt it was necessary to define the culture of their new nation. The spread of Western techniques allowed for a continued exchange between foreign ideas and indigenous art.

After the end of Nigeria’s civil war in 1970, it was time for an artistic rejuvenation. Artists like Uche Okeke and Chukwuanugo Okeke compulsively produced textile works during this period, reasserting the ideals of freedom that had been crucial to the earlier modernist movement.

The 1970s also saw Nigerian artists looking elsewhere for new ideas: rather than colonial powers, they looked to the global Black diaspora. This intermingling of Black ideas from around the world culminated in FESTAC ’77. This major international festival of Black art took place in 1977, a monthlong celebration of Black culture that put Nigerian Modernism in the spotlight for an international audience.

Ben Enwonwu, The Durbar of Eid-ul-Fitr, Kano, Nigeria 1955. © Ben Enwonwu Foundation. Courtesy of Tate Modern.

Typical characteristics of Nigerian Modernism

One of the main ideas of the Zaria Art Society was “natural synthesis,” referring to the merging of traditional indigenous Nigerian elements and modern Western practices to produce a brand-new artistic form.

This definition came to embody Nigerian Modernism and can be seen across works of different mediums. For instance, Grillo’s Mother and Child (1965) uses modern oil-on-canvas techniques to depict a traditional dynamic between a Yoruba mother and her child. Nwoko, one of the major architectural pioneers of the movement, designed the Dominican Institute in Ibadan using modern building methods as well as traditional local building materials to create a structure that looks wholly Nigerian.

Nigerian Modernism was not just defined by the style of physical objects produced but by an attitude. And a component of that was a spirit of rebellion. Kavita Chellaram, founder of Lagos gallery kó and Arthouse Contemporary, a Lagos-based auction house, lent several works to Tate Modern’s exhibition. “They rebelled against colonialism,” she said, of the Nigerian Modernists. “The British were trying to teach them to paint one way: landscape, portrait. But they said no; they wanted to show what they wanted to show.”

Bruce Onobrakpeya, The Last Supper 1981 © reserved. Courtesy of Tate Modern.

Key figures in Nigerian Modernism

A vast number of artists contributed to Nigerian Modernism. Some early pioneers include Onabolu, who planted the seeds of the movement, and Lasekan, whose political cartoons are a perfect representation of Nigerian anti-colonial expression.

Other key figures included wood-carving artist Justus Akeredolu, who trained in museum studies in the U.K. He was an acclaimed artist who had practiced in Nigeria in his youth but refined his techniques abroad.

The Osogbo school, started by Beier, helped define the trajectory of Nigerian Modernism from the 1950s to the 1960s. This school was an experimental art workshop where the creatively inclined were given materials and allowed to do as they pleased. It birthed visionary artists such as the painter, sculptor, and musician Twins Seven-Seven whose ecstatic canvases reflected his interests in dance, music, and sculpture. and Yinka Adeyemi, known for his Nigerian-style batik works and paintings. Other names to emerge from the school include Jimoh Buraimoh, who incorporated traditional Yoruba motifs into his painting; Rufus Ogundele, who reinvented linocut techniques with a Nigerian sensibility; and drummer-painter Muraina Oyelami, who combined abstraction and figuration in a new modernist style.

Ladi Kwali, Water pot (undated). © Estate of Ladi Kwali. Courtesy of Tate Modern.

Women artists in Nigerian Modernism

There were many women artists who played key roles in Nigerian Modernism. However, they often did not receive their due. Textile and bead artist Nike Davies-Okundaye, for example, was never formally allowed to become a member of the Osogbo school.

Although women artists did not receive the same recognition for their work at the time, that is gradually changing, particularly with the show at Tate Modern. Important Nigerian Modernist artists like the painter and art teacher Clara Etso Ugbodaga-Ngu, ceramist Ladi Kwali, and Davies-Okundaye are all featured in the exhibition.

“They’ve been too often sidelined,” said Emelife. “Nigerian Modernism isn’t a chorus of men alone….it’s a more complex and radical ensemble.”