Second only to the Mona Lisa as Leonardo da Vinci’s most stupendous achievement, The Last Supper (1495–98) is almost as famous for its degraded state as it is for its enduring power. With details barely readable today, it’s a ghost of its original self, suspended in a limbo of decay that has existed for almost as long as the painting has. Arguably, it is a victim of Leonardo’s genius, an artistic triumph subverted by a refusal to accept limitations.

Even at a time when the separation between disciplines like art and science was narrower than it is now, Leonardo (1452–1519) stood out as the quintessential Renaissance man. He famously filled dozens of notebooks with thousands of drawings and notes on anatomy, astronomy, botany, cartography, and paleontology, not to mention futuristic designs for flying machines and modern weapons of war (tanks, submarines, repeating firearms) that far exceeded 15th-century technology.

These efforts bolstered Leonardo’s aesthetic endeavors, but their quantity suggests that he was more interested in science than in art, a suspicion heightened by the numerous commissions he left unfinished. The Last Supper, however, was undone by Leonardo’s resort to unconventional techniques.

Located in the dining room of the former Dominican monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, The Last Supper was commissioned by Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, in 1495. Its theme, the Passover seder Christ celebrated with his disciples shortly before his arrest and crucifixion, captures his revelation that one of his follows will betray him while he offers bread and wine as symbols of his body and blood, originating the rite of the Eucharist.

Usually frescoes are rendered with water-based pigments on newly applied plaster that sets quickly, obliging artists to work on one small section at a time. This method didn’t comport with Leonardo’s methodical blending of tonal gradations to produce his signature sfumato effect. So he instead applied tempera paint al secco, i.e., to a dry ground comprising gesso, pitch, mastic (a kind of resin), and white lead paint.

This proved ill-suited to The Last Supper, which was situated on a thin exterior wall subject to fluctuations in temperature and humidity. Steam and smoke from the refectory kitchen damaged the painting, as did smoke from candles lighting the interior. In 1517 author Antonio de Beatis noted The Last Supper’s poor condition; in 1568 the noted biographer Giorgio Vasari pronounced it a total ruin.

Over the centuries, repeated stabs at restoration were made, which sometimes made matters worse. The earliest attempt was undertaken in 1726; the latest, a 20-year effort completed in 1998, stabilized the fresco by reversing previous renovations.

The Last Supper endured other indignities as well. In 1652 a doorway was cut into it. Occupying Milan in 1796, Napoleon’s army turned the space into a stable. In 1800 the refectory was inundated with two feet of water, leaving a bloom of green algae over the entire painting. And on August 16, 1943, the British Royal Air Force destroyed the building’s roof, nearly leveling the monastery; only sandbags and mattresses piled against the mural saved it from complete destruction.

Leonardo’s perfectionism had been a hallmark of his career from the start. Born the illegitimate son of a notary in the Tuscan town of Vinci, he entered the Florentine workshop of the painter and sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio as a garzone, or errand boy, at age 14, attaining full apprenticeship three years later. His handiwork first appeared in an angel occupying the lower left of Verrocchio’s The Baptism of Christ (1472–1475), an addition so superior to the rest of the scene that Verrocchio supposedly hung up his brushes for good when he saw it. Though this tale is apocryphal, it highlights Leonardo’s precocious skills; by age 20 he’d been admitted to a painter’s guild named for St. Luke, the patron saint of artists.

Leonardo’s restless ambition conflicted with his art from the beginning. Two early commissions, including The Adoration of the Magi (1478–1482), were abandoned when Leonardo moved to Milan to work for Sforza. In his letter to the duke seeking the job, Leonardo advertised his services as an engineer and arms designer before mentioning that he could paint.

Other unfinished projects include Saint Jerome in the Wilderness (c. 1480–1490) and a gargantuan equestrian monument of a horse commissioned in 1482 by Sforza. Measuring 28 feet in height, it progressed only as far as a full-scale clay model after the bronze promised for its casting went to producing canons instead.

Another mural, The Battle of Anghiari (1505), commissioned for the Hall of the Five Hundred in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio, suffered an even worse fate than The Last Supper’s. This time, Leonardo laid oils over a thick, waxy base, causing the pigment to run. To speed drying, he placed lit braziers in front of the painting, which saved its bottom half but left the top portion a mess of mingled colors. The piece was eventually destroyed during an expansion of the hall under Giorgio Vasari, who painted his own frescoes on top of it.

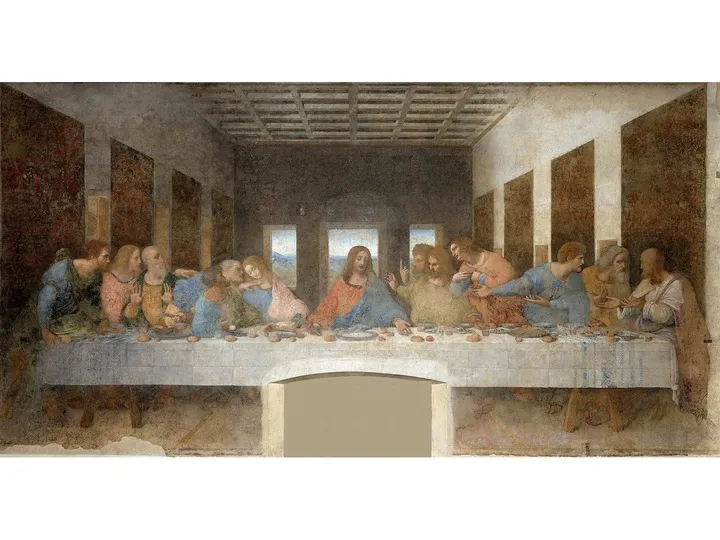

The Last Supper decisively broke with other treatments of the theme, which usually placed subjects on both sides of the dinner table. Leonardo put them all behind the table, facing outwards. Christ is seen standing, occupying the center without the traditional halo signaling his divinity, a gesture conforming to the Renaissance’s revival of humanism by emphasizing Jesus’s mortality.

His head marks the vantage point of a forced perspective leading to a trio of windows in the background that look out on a distant landscape. Leonardo flanked Jesus with his followers set six on either side, respectively divided into clumps of three. Most are seen reacting to the news of treachery in their ranks by gesturing as if to say, “Is it me?” The actual villain, Judas, is isolated on the far left clutching his payment for selling Jesus out.

Christ, however, remains calm, as does his youngest disciple, John, seen sleeping on the shoulder of Peter to Jesus’s left. Jesus and John are separated by a V-shaped opening that some claim is a vaginal sign for Mary Magdalene.

Leonardo presented Christ as the pyramidal inverse of the V, a fulcrum for a symmetrical, platonic composition where certain elements—the windows, the spacing of the apostles, and Jesus’s triangular form—are triads alluding to the Holy Trinity.

Today The Last Supper is a gossamer veil of shapes that nearly disappear into the wall. Yet its power to awe remains undiminished, a testament to an unbounded talent.