As the northern hemisphere nights start drawing in, many will be looking forward to settling down to do some hygge with streamed re-runs of The Bridge or The Killing (or last winter’s highly recommended new Netflix series The Åre Murders). Scandiphiles will be delighted to know, then, that another kind of “Nordic noir” opens on 9 October at the British Museum, in London, a free survey that similarly peeks beyond the clichés of apparently idyllic Nordic life—all those chic, minimalist trays of cardamom buns—to reveal hidden darknesses lurking beneath.

Bringing together more than 150 works by 100 different artists, the exhibition begins with the original enfant terrible of northern psychodrama, Edvard Munch. One of two woodcuts by the artist, Munch’s typically melancholic Gammel fisker (Old fisherman, 1897) is a study of a man from a distant time, as his back-breaking manual labour appears to leave impressions and incisions on the skin and the soul alike. Munch’s darkness will be brief, though, as most of the exhibited works are closer to our moment.

Gammel fisker (old fisherman, 1897), one of two woodcuts by the Norwegian Edvard Munch in the show © The Trustees of the British Museum

Curated by Jennifer Ramkalawon, the curator of Western Modern and contemporary graphic art at the museum, Nordic Noir tracks a broadly chronological structure, which swiftly moves beyond Munch by placing particular emphasis on how works on paper responded to the political transformations of the Nordic countries since the Norwegian’s death in 1944. (Against his wishes, Munch was given a state funeral by the Nazi puppet regime despite being condemned by Hitler as a Modernist “degenerate” in the 1930s.) While it can be tempting to see the post-1945 period in the Nordic countries as one of economic renewal, carefree social democracy and communal harmony, the reality was far more complex (and often more thrilling) as artists fought with the state, with each other, and with their own stranded place on the periphery of the global art market. During her research, Ramkalawon was interested to know “what kind of art is produced where artists are awarded substantial grants and opportunities not open to UK artists”, and if those conditions shaped the work that was produced.

Subtle interrogation

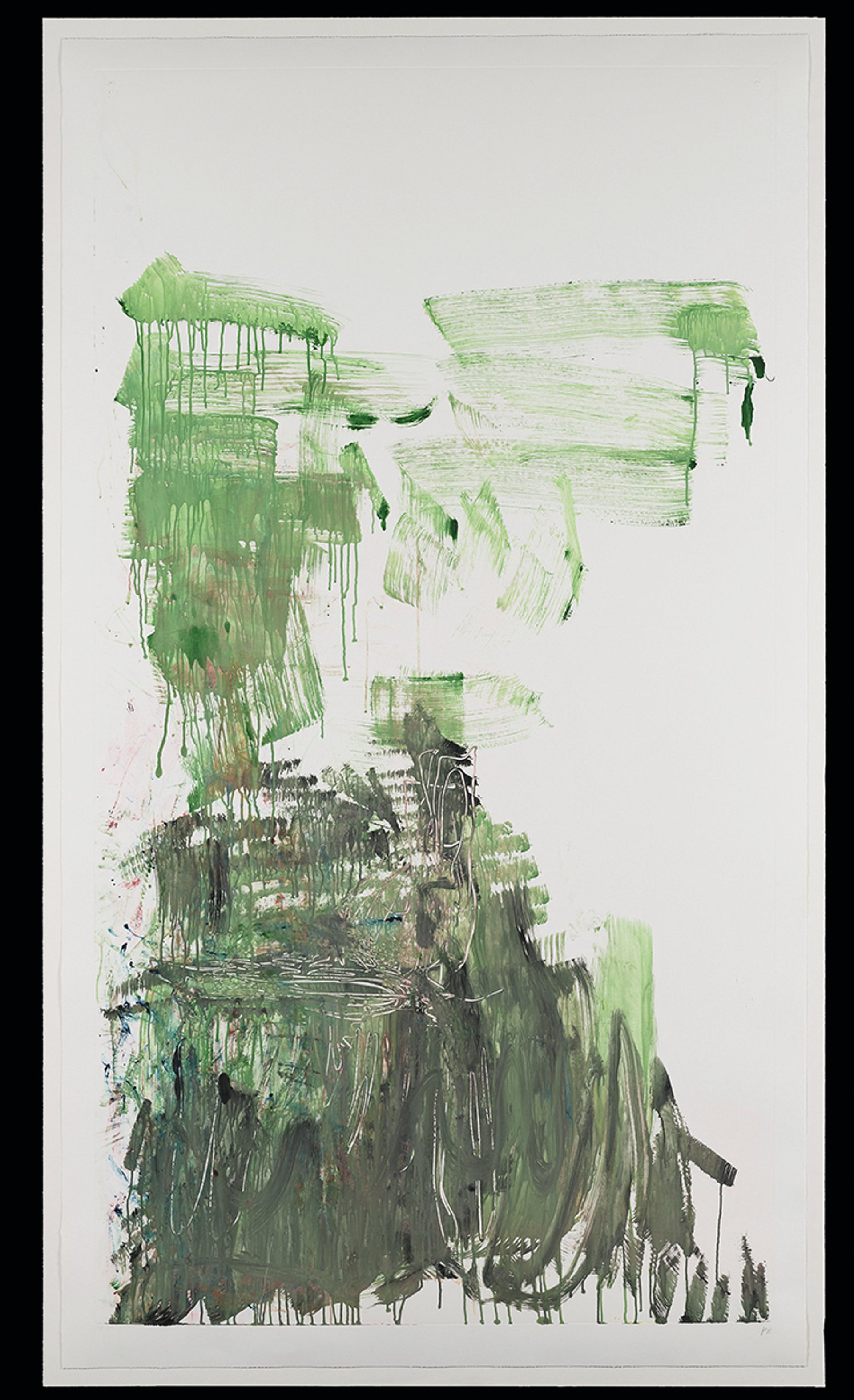

The show moves forward in time, exploring the ecocritical experiments with mineral pigment by the contemporary Finnish Japanese arboreal artist Yuichiro Sato (2019), Anna Zimmerman’s charcoal drawings of historical costumes (2023), and watercolours by Maria Nordin. In Nordin’s Act of Comfort (2022), we see the back view of the artist holding huge piles of clothes under each arm, a subtle interrogation on unacknowledged women’s labour in Sweden, a country that is often seen as one of the global pioneers of gender equality. On display will also be late abstract works by Per Kirkeby, including an untitled monotype in green, yellow and black ink (2016), which the much-loved Dane made after he suffered a serious brain injury in 2015 and gave up painting altogether.

Untitled (2016) by the Danish artist Per Kirkeby Reproduced by permission of the artist’s estate; © The Trustees of the British Museum

But it will be particularly exciting to see works by less-familiar artists from the region, such as those by the Norwegian radical left-wing collective GRAS (grass), which was established by Willibald Storn in 1969. Holed up in a modest Oslo workshop, GRAS made work that criticised US foreign policy, particularly the Vietnam War, while also ironically adopting the iconography of American Pop art by using striking contemporary imagery. “Storn is still politically active in his late 80s,” Ramkalawon says, and can often be found “making protests against consumerism or the dangers of climate change by sitting on the metro or outside the Grand Hotel, Oslo, often semi-naked and wearing a wolf’s head”. Who said the Norwegians were strait-laced? Many works have never been seen outside the Nordic region, from Danish prints reacting to the anxieties and paranoia of the Cold War to Finnish Concrete art, led by the iconoclast Lars-Gunnar Nordström, a style of hard-edged graphic work that was unpopular with both the public and critics in the 1950s.

Artists fought with the state, with each other, and with their own stranded place on the periphery of the global art market

It is not all politics and eccentric avant-gardists, however. Audiences seeking visions of fjords and nocturnal landscapes (Rina Charlott Lindgren) and references to Nordic myths (Sverre Malling) will also find charming and light-footed objects here, such as woodcuts celebrating traditional Nordic hunting methods and megafauna. In Suopan (Lasso, around 1928-34), John Savio, the first Sami artist with a formal art education, depicts an Indigenous herder lassoing reindeer with his trusted Lapponian dog in a blizzard. Henrik Finne’s Fiskere (Fishermen, 1942) sees three hardy figures, all in heavy yellow bib overalls and straddling a flimsy wooden boat, hauling fish from the frozen water with a crosshatched net while hard-edged abstracted patterns recede into the distance behind.

New cultural perspectives

Perhaps the most celebrated Nordic artist working today, the Swede Mamma Andersson, is represented by The Fallow Deer (2016), a striking woodcut on rice paper of a regal red deer in profile set against an earthy green background. Despite being some of the happiest people in the world (the World Happiness Report routinely places the Nordic countries in the top ten; Finland, Denmark, Iceland, and Sweden took the top four spots in 2025), with highly advanced mixed economies, it is extraordinary how often the North is seen as a land of rugged loners in touch with unyielding landscapes of snow and trees amid precious little sunlight. The exhibition appears to substantiate that view while also offering new perspectives on Nordic life and culture.

The research, conservation and acquisition project that includes the Nordic Noir exhibition has been supported by a substantial grant from the charitable organisation AKO Foundation (founded by Nicolai Tangen, the chief executive of Norway’s sovereign wealth fund). This grant has culminated in almost 400 works by artists from Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden being brought into the museum’s collection. It forms part of a much broader fundraising drive under the museum’s director, Nicholas Cullinan, to keep the museum financially sustainable and fund its enormously ambitious masterplan.

Nordic Noir: Works on paper from Edvard Munch to Mamma Andersson, British Museum, 9 October—22 March 2026