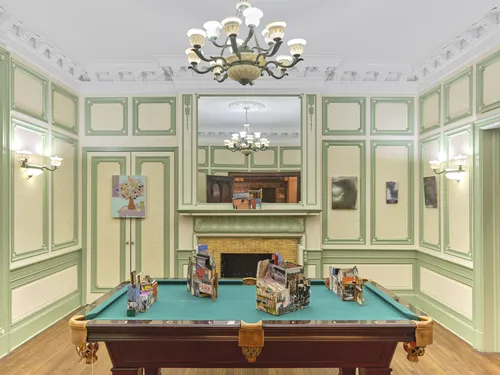

For the past two years, Manhattan’s Estonian House has hosted Esther, an alternative art fair, across its enchanting Beaux Arts floors. Gallerists Margot Samel and Olga Temnikova founded the event in 2024, gathering just a few dozen galleries to participate; it’s much smaller than Frieze New York, which runs at the same time. “From the beginning, Esther was imagined as a way to slow the pace of the fair experience,” Samel told Artsy. She knows many collectors who have recently stepped away from the endless fair circuit. “For them, Esther felt closer to an exhibition; something to move through attentively.”

Though the fair was originally conceived as a one-off and extended twice, it’ll end this May with its third edition—“enough [time] to fully explore the format without pretending it needed to become something permanent,” explained Samel. It’ll be a loss, but Esther is just one of many events rethinking the traditional fair model and ratcheting down pressure for gallerists and collectors alike.

Major players like Art Basel and Frieze pack hundreds of cookie-cutter booths into their sprawling and often industrial spaces. They promise galleries a reputational boost and access to new collectors at a steep toll, at times costing $20,000 or more in booth and transportation fees. As Samel told Artsy last year: “Adding a few wall washers or spotlights can easily cost $1,000–$2,000, electrical outlets range from $200–$600, [and] building extra walls can run anywhere from a few hundred to tens of thousands of dollars.”

Alternative fairs focus instead on accessibility and affordability. Most offer free entry to guests and low exhibitor fees. This translates to a looser atmosphere and inspires visitor curiosity. “People tend to stay a lot longer, see everything, and talk a lot more than at a large fair,” noted gallerist Chris Sharp, who launched Place des Vosges in Paris in 2024 and Post-Fair in Los Angeles a year later. He approached both with the same ethos: “How do you make [visitors] want to stay? You offer them a unique and beautiful setting in which to view art without the crowds.”

Experimental venues and stagings are indeed major draws. Last year, the nonprofit association Basel Social Club (BSC), largely funded by Swiss institutions like the Migros supermarket empire, packed the Art Basel crowd into the former private bank Vontobel. In London, the self-described “non-fair” Minor Attractions—founded by gallerists Jonny Tanna and Jacob Barnes—launched in 2023 across multiple locations in Soho and London Bridge. Since 2024, participants have paid roughly $6,200 to take over a room at art collector Rami Fustok’s buzzy Mandrake Hotel.

Such domestic or intimate settings offer tonal shifts, stripping away the intimidation of larger fairs’ labyrinthine layouts. This atmosphere may be particularly appealing to novice collectors just finding their feet, and it is also invaluable to participants. When Cedric Bardawil showed works at Minor Attractions 2025, “some visitors stayed for as long as two hours,” he told Artsy. “With a comfortable bed to sit on, we could play music in the room and create a real vibe.”

Yet these offbeat models also invite their own issues. Just like at large fairs, renting space and building out walls and lighting eat into the budget; the difference is that organizers absorb these costs rather than exhibitors and visitors. For gallerist Brigitte Mulholland, whose inaugural 7 Rue Froissart fair in October 2025 offered free entry and charged less than $5,000 per exhibitor, this meant constant problem-solving: She says she found, leased, insured, installed, and deinstalled the fair space on her own.

The risks aren’t only financial; the format itself sometimes fails. When Basel Social Club took over roughly 124 acres of sprawling farmland in 2024, gallerist Dennis W. Hochköppeler—whose Cologne-based gallery Drei pulls double duty by participating in BSC and Art Basel concurrently—witnessed what happens when experimentation runs up against reality. Although he said this edition was “extremely well received, especially by young audiences,” he also shared that some visitors struggled to use the special art fair app and that the land’s expanse impeded communication between guests. Nevertheless, Hochköppeler noted, “Unpredictability makes up the charm of the whole thing in comparison to a conventional fair.”

While these new art fair environments bring up financial and logistical trade-offs, the end result is often worth the struggle. Though Mulholland ultimately took a loss of “a touch over $5,000” on producing the inaugural 7 Rue Froissart—“mainly due to unexpected material costs and [a] last-minute scramble for builders”—she was happy to watch collectors and curators filter in while gallerists forged new relationships. “Everything felt very organic and honest,” she noted. “It was always a risk, [but] it’s important to keep art open and accessible, and that was also what set us apart.”

Mulholland and her peers are both bucking tradition and drawing on a robust history. Since the first crop of modern and contemporary art fairs began with 1967’s Cologne Art Market and Art Basel’s launch in 1970, smaller events have drawn gallerists and collectors seeking more close-knit affairs. In 1996, art dealer Rupert Goldsworthy packed sixteen international galleries into an empty East Berlin department store for Berlin Mitte ’96, set against the backdrop of the first annual European Art Forum, located at the expansive Messe Berlin Exhibition and Trade Complex (which was itself formed out of frustration with Cologne’s fair).

One of the first major constellations of these events emerged in Miami after the seismic impact of Art Basel Miami Beach in 2002. Other smaller fairs quickly set up shop, with NADA Art Fair, by the nonprofit New Art Dealers’ Alliance group, charging $2,500 per booth in 2003, and Scope Miami charging $5,000 per participant for their TownHouse Hotel–set event in 2004—a steal compared to the $35,000 charged for some shared booths at Basel. This trend of major fairs inspiring smaller, satellite events continued through the late 2010s as the market grew saturated, expanding from fewer than 50 fairs in the early 2000s to over 400 by 2019, according to The Observer.

When the pandemic arrived and art selling moved online, many collectors and gallerists sought to trim their fair schedules when the industry reopened. Smaller, boutique formats with only a few dozen participants became attractive alternatives; Esther, Basel Social Club, 7 Rue Froissart, and Minor Attractions all sprang up in the past five years, while other small fairs took the pandemic as time to pause to recharge and rethink their model.

While those events run concurrently with major fairs to capitalize on the large crowds, some, like the NOMAD series in St. Moritz, Switzerland, and the Hamptons, New York, intentionally stage their editions outside major art world events and centers to create boutique experiences. When Half Gallery’s director Erin Goldberger and founder Bill Powers launched Upstairs Art Fair in 2017, they also settled on an event outside the fair calendar—and the city. A big red barn in Amagansett, New York, became their home for three years, attracting collectors and locals with a strong showcase for emerging talent.

When Upstairs Art Fair relaunched in 2025 after a six-year, COVID-induced break, it moved to the Hotel Grand Amour in Paris, running alongside Art Basel Paris. “Smaller projects like Upstairs Art Fair certainly shouldn’t replace an institutional fair,” Goldberger told Artsy. “We still are a part of them as well, but it definitely makes the stakes and stresses lower.” This lowered pressure, she noted, allows for open, casual dialogues about much more than just what’s sold out.

Indeed, when galleries cohabitate in smaller fairs, cooperation can thrive. After showing works next to each other at 7 Rue Froissart, New York’s Slip House and London’s Chili decided to share a booth at the upcoming Felix Art Fair in Los Angeles. Mulholland was thrilled. “It was absolutely one of the goals of the fair—to foster collaborative relationships between galleries,” she said.

This embrace of slow, purposeful connection explains why many alternative fairs are resistant to scaling up or, as in Esther’s case, were initially conceived as one-offs. “In this moment, intimacy is more important than scalability,” Mulholland told Artsy. “I think the art world is in a real moment of sea change, and the notion that bigger is better has proven to be what bursts first when the bubble collapses.” Slowing down, at a smaller scale, doesn’t have to mean losing business. As Hochköppeler keenly noted: “If a collector wants something, they’ll let you know.”